From sight to insight: Unravelling student interpreters’ usage and perceptions of live captioning in Chinese–English simultaneous interpreting

University of International Business and Economics, Beijing, China

gm@uibe.edu.cn

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5772-2272

Yuxing, Xie

University of Macau, Macau SAR, China

mc33107@um.edu.mo

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-3238-6680

Lili, Han

Macao Polytechnic University, Macau SAR, China

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8995-2301

Victoria Lai Cheng, Lei

University of Macau, Macau SAR, China

viclcl@um.edu.mo

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7125-9579

Defeng, Li*

University of Macau, Macau SAR, China

defengli@um.edu.mo

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9316-3313

* Corresponding author

Abstract

Whereas computer-assisted interpreting (CAI) tools hold potential for simultaneous interpreting (SI), there is limited understanding of the way interpreters interact with and process live captioning during interpreting tasks. This study examined the interaction patterns and perceptions involved in live captioning among 27 student interpreters engaged in Chinese–English SI. Through a triangulated quantitative methodology incorporating eye-tracking data, temporal metrics, and participant feedback, we assessed the ways in which live captioning influences visual processing, temporal synchronization, and subjective experiences during SI tasks. The results reveal that student interpreters relied extensively on visual transcription during SI tasks. This heavy reliance on captioning appeared to affect their processing patterns, as evidenced by a gradually increasing ear–voice span (EVS) throughout sentence sequences. Whereas these interpreters generally viewed live captioning as a valuable CAI tool, their subjective feedback highlighted the need for customizable interfaces to accommodate individual processing styles and to optimize usability. These findings underscore the importance of integrating live captioning strategically into SI, together with targeted training to enhance interpreters’ use of tools and their attention management. This study contributes to ongoing research on CAI and SI, aligning itself with emerging perspectives on augmented interpreting that emphasize human–machine collaboration to enhance interpreter performance. It advocates a balanced evidence-based approach to incorporating such technologies into professional practice.

Keywords: computer-assisted interpreting, CAI, eye-tracking, simultaneous interpreting, SI, live captioning, interpreter training

1. Introduction

The field of interpreting is experiencing a transformation driven by technological advancements, particularly those in automatic speech recognition (ASR) (Fantinuoli, 2017; Pöchhacker, 2016). This evolution has given rise to computer-assisted interpreting (CAI), which represents the convergence of technological innovation and interpreting practice. The integration of technology into interpreting has garnered increasing attention from academic researchers and practitioners alike, and this has resulted in a growing body of research that is examining the effectiveness of CAI tools in simultaneous interpreting (SI) (Desmet et al., 2018; Fantinuoli, 2017; Frittella, 2023; Prandi, 2023).

Despite this growing body of research (Defrancq & Fantinuoli, 2021; Yuan & Wang, 2023), several critical gaps remain. Most studies have prioritized outcome-based evaluations over process-oriented analyses, offering limited insight into the ways in which interpreters interact visually with CAI interfaces during real-time SI. In addition, little is known about the cognitive mechanisms that guide interpreters’ attention between the primary task and the supplementary CAI input. Finally, whereas technical assessments of CAI tools exist, the empirical evidence of interpreters' usage patterns and subjective experiences in authentic settings remains scarce.

Responding to this research gap, the present study explored both the interactions (from “sight”, i.e., eye-tracking data) and perceptions (to “insight”, via questionnaires and interviews) of student interpreters using automatic live captioning during SI. By focusing on process-oriented analysis, this research delivered empirical data on CAI integration in SI that should inform future developments with CAI tools and promote the well-informed adoption of technology in interpreting practice.

This study is situated within the emerging “augmented interpreting perspective”, which frames CAI integration as an evolving collaboration between human interpreters and AI-driven tools (Fantinuoli, 2023; Fantinuoli & Dastyar, 2022). This framework conceptualizes technology not merely with regard to its usability and efficiency, but also in relation to its influence on interpreter workflows and professional identity, highlighting as it does the need to examine both the cognitive and the perceptual dimensions of tool use in SI.

2. Literature review

2.1 The evolution of CAI tools

Despite ongoing technological advances, the adoption of CAI tools has consistently remained limited in interpreting practice. Wan and Yuan (2022) found that more than two-thirds of student interpreters still relied on handwritten notes during interpreting tasks. Among those who used digital resources, general online search engines and electronic dictionaries were the most common rather than dedicated CAI terminology management tools. Similarly, Riccardi et al. (2020) found that only 8.1% of interpreter trainers regularly used interpreter-specific glossary software. Some interpreters expressed concerns about the possible impact of these tools on interpreting authenticity, whereas others viewed them as possible distractions or considered them to be unnecessarily complex. A comparative study by Prandi (2023) highlighted the fact that interpreters who used InterpretBank’s manual functionality did not experience a significantly reduced cognitive load compared to those using traditional PDF glossaries. This indicated that whereas CAI tools introduced innovative features, their advantages did not outperform conventional methods significantly. Additional barriers included financial constraints and the limited integration of CAI tools into interpreter training curricula (Fantinuoli, 2018; Fantinuoli & Prandi, 2018; Prandi, 2020; Riccardi et al., 2020).

Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and ASR has initiated a new phase in CAI tool development. Recent research highlights the potential of these technologies to enhance the adoption of CAI tools in interpreting practice (Fantinuoli, 2023; Frittella, 2023; Prandi, 2023). Various implementations of ASR-integrated CAI tools have been explored in recent research. For instance, Desmet et al. (2018) used PowerPoint slides to simulate an ASR-enhanced CAI tool for number recognition (Figure 1a). The InterpretBank ASR prototype has demonstrated several visualization approaches, including full transcripts with highlighted numbers and terminology (Figure 1b) and focused number displays (Figure 1c) (Defrancq & Fantinuoli, 2021; Desmet et al., 2018). Other designs have featured displays of key terminology, numerical data, and named entities (Figure 1d) (Frittella, 2023). These developments align with the emerging concept of augmented interpreting, which emphasizes human–machine collaboration as a defining element of future interpreter workflows (Fantinuoli, 2023; Fantinuoli & Dastyar, 2022).

Figure 1

Interfaces of ASR-integrated CAI tools in empirical studies

|

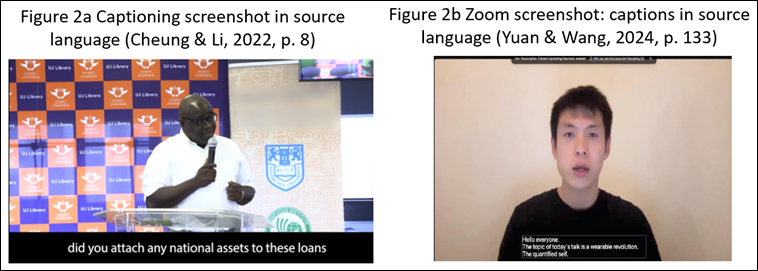

The advancement of streaming ASR technology has expanded the integration of automated tools into SI workflows even more (Guo et al., 2023, 2024). Automated live captioning, also known as closed captioning or live transcription, instantly transcribes spoken language, presenting it as text even as the speech continues (He et al., 2019; Jurafsky & Martin, 2024). Research has demonstrated the potential benefits of these tools, with Cheung and Li (2022) reporting improved holistic accuracy in SI using their captioning interface (Figure 2a). Similarly, Yuan and Wang (2023, 2024) have found that the captioning features of Zoom Meetings (Figure 2b) enhanced interpreters’ performance in both specific problem triggers and overall accuracy. Whereas the integration of live captioning technology is becoming increasingly accessible through various software platforms, research into its effectiveness in the SI workflow, particularly from both product and process perspectives, remains an emerging area that requires further investigation.

Figure 2

Comparative displays of captioning tool interfaces

2.2 Visual–verbal information processing in SI

In an increasingly multimodal world, interpreting professionals are frequently being exposed to complex inputs that combine audio, text, and other visual cues. This trend has notable implications for the interpreting profession (Seeber, 2017). At international conferences, it has become common for interpreters to work with both audio and visual text sources, a mode referred to as “SI with text”. According to a survey by Cammoun et al. (2009), 98% of 50 professional interpreters reported using the available text when conducting SI with text. However, studies on the ways interpreters process and integrate visual–verbal information during SI remain limited due to the complexity of interpreting processes. The question of how interpreters interact with visual–verbal information in real-time remains largely unexplored therefore.

Studies examining visual–verbal information processing have revealed complex patterns of interaction between visual and auditory channels. Research indicates that both interpreter trainees and professionals tend to rely heavily on textual information when it is available. For instance, Yang et al. (2020) investigated the way interpreter trainees manage SI with text from L1 to L2 under rapid speech conditions; they found that 75% of their participants relied predominantly on visual inputs, whereas only 25% favoured auditory cues. In another study which focused on professional interpreters working from their L2 to their L1, Chmiel et al. (2020) examined their performance with challenging accents and intentionally incongruent items. Their findings revealed a stark contrast in the accuracy rates: 90% for congruent items versus 25% for incongruent ones. This demonstrated the interpreters’ strong reliance on visual information even when it conflicted with the auditory input.

Research has also explored the way interpreters use textual information, specifically whether it primarily helps with source speech comprehension or serves as memory cues for production. Seeber et al. (2020) observed that professional interpreters working from their L2 to their L1 exhibited a distinct visual lag pattern during SI with text. Their eye movements typically focused on the sentence preceding the current spoken input, suggesting that interpreters rarely look ahead for anticipation. This visual focus aligned more closely with their verbal output, which followed the original speech by approximately 2–3 seconds. These findings suggest that interpreters may use written text primarily to support production rather than comprehension, possibly employing it as a strategy to reduce their short-term memory load during lexical retrieval.

Regarding the coordination of auditory input, visual input, and verbal output, Zou et al. (2022) conducted a fine-grained analysis of professional interpreters’ temporal metrics during L2 to L1 SI with text. Their research identified an “ear-leads-eye” pattern in which visual attention typically followed auditory input by about 4 seconds. The study categorized interpreters into three groups based on attention allocation: ear-dominant, eye-dominant, and ear-eye-balanced. Each group demonstrated distinct performance characteristics: eye-dominant interpreters showed enhanced accuracy, which could be attributed to the written source text serving as a supplementary aid to information processing and helping to prevent working memory overload. In contrast, the ear-dominant interpreters achieved greater fluency by following the source speech rhythm closely.

Research on visual information processing in SI with live captioning has revealed additional insights. Li and Fan (2020) studied five professional interpreters performing L2 to L1 SI with auto-transcribed YouTube captions. Their findings indicated that numbers in captions received the highest level of attention, followed by low-frequency words and proper nouns, whereas common words received minimal attention. Notably, the participants devoted significantly more attention to the captioning area than to the speaker’s face. Yuan and Wang (2023) corroborated these findings in their study of the functionality of live captioning during Zoom meetings; they observed similar visual-attention patterns that prioritized the captioning zone over the speaker’s face.

While existing studies have illuminated various aspects of visual–verbal processing in SI, research specifically examining interpreters’ interaction with automatic live captioning during SI tasks remains sparse. In particular, we lack triangulated empirical data to enable fine-grained analysis of this increasingly prevalent CAI tool.

2.3 User experience and tool adoption in SI

Early research into CAI tool preferences has focused primarily on the display of numerical data and terminology. For example, Defrancq and Fantinuoli’s (2021) study on the InterpretBank ASR prototype, which displays full transcriptions with numbers prominently highlighted, assessed the participants’ visual preferences for displaying numerical data and units. Some interpreters favoured displaying numbers only whereas others preferred a combined display of numbers and units. In a more extensive survey conducted as part of the Ergonomics for the Artificial Booth Mate (EABM) project (2021), which included 525 predominantly professional interpreters, the preferences for CAI tool layouts were examined in detail. The findings indicated that 59% of the interpreters favoured a vertical layout where newly recognized items appeared below previous ones. In addition, 80% of the participants expressed a preference for keeping recognized items on screen for extended periods and 40% preferred either separating terminology and numbers into left and right columns or integrating both into a single column. In the case of distinguishing newly recognized items, 38% of the respondents favoured bold text.

Building on these initial investigations of display preferences, Frittella’s (2023) comprehensive analysis of SmarTerp, which displays terminology, names, and numbers in separate columns, provided additional insights into interpreters’ preferences. While some of the participants preferred a full transcript, others found segmented displays more manageable. A notable challenge was the consistent 2-second display latency, which added cognitive strain. Frittella’s study also highlighted the difficulties interpreters encountered when locating specific items on the screen, suggesting that certain design aspects of the tool hindered its usability. Beyond layout and timing, Frittella underscored the need for accuracy in CAI tools, as any inaccuracies directly affected the interpreting quality. Whereas terminology and number suggestion tools were considered to be potentially helpful in enhancing the precision of the interpreting outcomes, concerns were expressed that these suggestions could detract from focusing on non-highlighted portions of speech. This finding calls for careful assessment of the actual effectiveness of such tools and the possible drawbacks inherent in over-emphasized suggestions.

Other studies have expanded the scope to examine preferences specifically for transcription and captioning functionalities. For instance, Saeed et al. (2022) used focus groups to examine interpreters’ preferences for remote SI platforms, with a consensus emerging in favour of including full transcripts and presentations in these platforms. Cheung and Li (2022) also examined interpreters’ experiences with captioning tools, finding that a single-line caption display negatively affected their interpreting fluency. Their study suggested that a more comprehensive caption display, including complete sentences, would probably improve interpreters’ processing and output. Despite these initial insights into CAI tool design and preferences, research on the usability of live captioning remains fragmented, with questions about detailed configuration still being underexplored and warranting further investigation.

3. Research questions

Existing research on CAI tools and visual–verbal processing in SI has highlighted the growing reliance on visual inputs, the evolving integration of automated tools such as live captioning, and the need for user-centred design. However, empirical studies examining interpreters’ real-time interaction with live captioning during SI remain limited. To respond to this gap, this study investigated the ways in which student interpreters interact with and perceive live captioning during SI. It focused on responding to these two research questions:

· RQ1: How do interpreters interact with live captioning during SI, as evidenced by eye-tracking metrics, temporal measurements, and self-reported processing strategies?

· RQ2: How do interpreters perceive the live captioning tool in SI tasks, as revealed through questionnaires and interviews?

These complementary research questions were formulated to provide a comprehensive understanding of the integration of live captioning into SI.

4. Methodology

This study employed a triangulated, predominantly quantitative research design that integrated eye-tracking data, temporal metrics, and subjective measures (questionnaires and interviews) in order to investigate interpreters’ interactions with and perceptions of live captioning during SI. The following sections describe in detail the participants, materials, experimental procedures, and data-analysis methods.

4.1 Participants

In our study, we recruited 27 students from several universities in Macao, all of them about 20 years of age (26 female and one male), majoring in English or Translation Studies with Chinese as their L1 and English as their L2. We selected participants ranging from the third year of bachelor’s programmes to the first year of master’s programmes, all of them meeting the English proficiency entry requirements of the University of Macau, which indicated a good command of English. These requirements included a College English Test (CET) level 6 score of 430, a TOEFL score of 550 on the paper-based examination/80 on the Internet-based examination, an IELTS overall score of 6.0 or above, or passing the Test for English Majors (TEM) Level 4 or Level 8. All of the participants had limited experience in performing SI tasks and minimal exposure to CAI tools.

Importantly, although gender was not a selection criterion, the sample was heavily female-biased (≈96 %), exceeding the ∼70 % female share commonly reported for translation and interpreting cohorts (CSA Research, 2017). This imbalance limited our ability to examine gender‑related differences and so it should be borne in mind when interpreting the findings.

4.2 Materials and tools

We selected materials for this study from the Speech Repository of the Directorate-General for Interpretation at the European Commission,[1] using beginner-level Chinese speeches from the general domain that suited the participants’ initial exposure to SI. One speech transcript was edited to 720 characters and recorded by a native Mandarin speaker. The recording was adjusted to maintain a speech rate of 180 characters per minute, which previous research has identified as optimal for Chinese SI (Li, 2010), therefore making the entire video four minutes long.

The interpreting quality was assessed using a four-dimensional 8-point scale (Han & Lu, 2021). The participants achieved a mean score of 5.91 (SD = 1.19, Median = 6), indicating the appropriateness of the selected materials to this participant group.

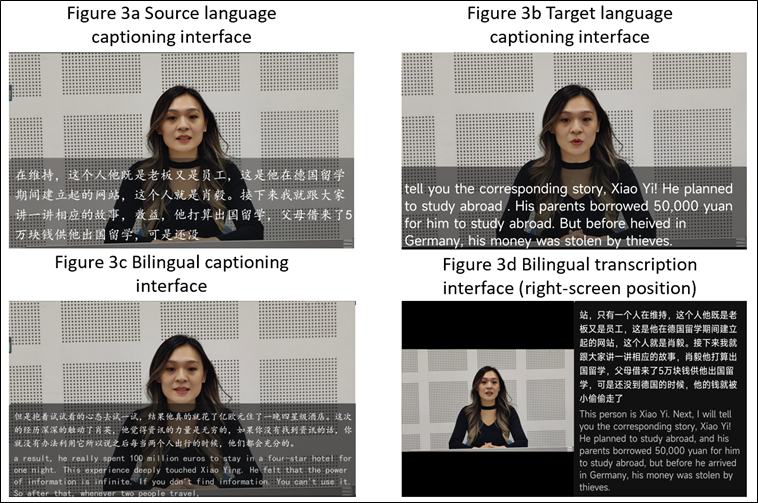

For automatic transcription, we employed iFlyrec,[2] which was selected for its Chinese language accuracy and flexible interface options. As shown in Figure 3, this tool offers various customizable features, including display options in the SL (Figure 3a), automatically translated TL (Figure 3b), and a bilingual format (Figure 3c). These displays can be positioned anywhere on the screen, adjusted for font style and size, and formatted to suit user preferences. According to the iFlyrec specifications, the tool achieves a word error rate (WER) of 2% and a transcription latency of 0.2 seconds.

Figure 3

Examples of interface configurations of the iFlyrec tool

|

After running iFlyrec with our materials, we annotated the outputs manually. The actual average WER was 2.99% and the mean latency was 1.11 seconds per sentence – slightly higher than the tool’s official benchmarks but within acceptable limits for our study. To standardize the interpreting materials, we used the STKaiti font at size 30 with 1.5 line spacing. To ensure consistent technical performance across the participants, we pre-recorded the tool’s transcription output rather than using real-time transcription during the experiment. This approach eliminated potential variations in WER and latency due to technical or network problems while maintaining the representation of the tool’s real-time performance characteristics.

Once the video began playing, the transcription appeared automatically word by word without requiring any manual operation. Given that the complete speech transcription would exceed the capacity of a single screen and require automatic scrolling (which would complicate eye-tracking analysis), we divided the video into three parts of equal length. For each part, the transcription began from the top line of the screen and continued until it reached the bottom of the screen without any scrolling occurring. After completing the interpreting of one page, the participants could press any keyboard key to proceed to the next part.

4.3 Experiment procedure and settings

Prior to the main experiment, the participants completed a 5–10-minute practice session at home to familiarize themselves with the SI task and the experimental setup. They submitted video recordings of these practice sessions to verify their procedural compliance. The main experimental session was conducted in an eye-tracking laboratory under controlled conditions.

The study employed a Tobii TX300 Eye Tracker for the data collection, following the configuration guidelines established by Holmqvist et al. (2015). The setup included: a 23-inch LCD screen with 1920 * 1 080-pixel resolution; a viewing distance of 60–65 cm between participant and screen; individual calibration before each task; and instructions to minimize head movement during data collection.

Each experimental session lasted approximately 1.5 hours and comprised multiple tasks, including the SI with automatic live captioning task. To control for order effects, the task sequence was randomized across the participants. Prior to the SI task, the participants received a glossary and were given up to five minutes for preparation. The task itself lasted 4–5 minutes and it was followed by a brief semi-structured retrospective interview. At the conclusion of the experiment, the participants completed a questionnaire. Owing to the complexity of the experimental design and the focus of this study, the additional data collected during this experiment will be analysed in a future research project.

4.4 Data analysis

Our data comprised three main types: eye-tracking data, temporal metrics, and subjective data.

4.4.1 Eye-tracking data

For the eye-tracking data, our analysis was conducted using Tobii Studio, employing the I-VT (Velocity-Threshold Identification) fixation filter. In this method, fixations are identified as periods in which the eye’s velocity remains below 30°/s for a minimum duration of 60 ms (Olsen, 2012). These settings are consistent with Tobii’s default parameters and are widely used in eye-tracking studies. To assess the eye-tracking data quality, we adhered to the guidelines outlined by Hvelplund (2014), evaluating three key metrics: Mean Fixation Duration (MFD), Gaze Time on Screen (GTS), and Gaze Sample to Fixation Percentage (GFP). We employed the methodology of Cui and Zheng (2021) to exclude data that fell more than one standard deviation below the mean in any of these metrics. Only those participants with valid data in at least two of the three metrics were included in further analyses. After evaluating the 27 subjects, we found that the average values for the MFD, GTS, and GFP were 0.26, 0.49, and 0.53, respectively, with standard deviations of 0.08, 0.24, and 0.23. The one-standard-deviation cutoffs were therefore 0.18 for MFD, 0.25 for GTS, and 0.30 for GFP. Subjects 14 and 15 did not meet these criteria for the MFD and GFP, while subjects 20 and 21 failed to meet the GTS and GFP thresholds. Therefore, the eye-tracking data from 23 participants were retained for further analysis.

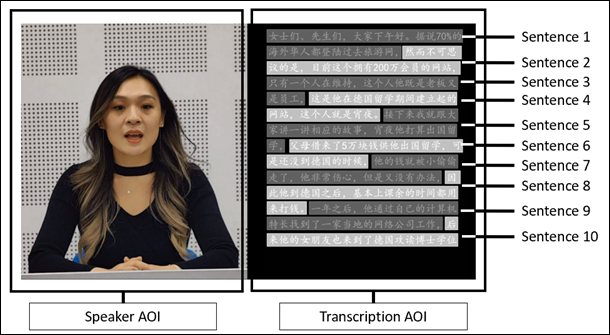

Following the data-quality assessment, we proceeded with analysis at both the global and the sentence level. Two layers of areas of interest (AOIs) were defined. At the global level, the screen was divided into two AOIs: the speaker AOI on the left and the transcription AOI on the right, as shown in Figure 4. For these areas, we collected data on total fixation duration (TFD), fixation count (FC), and MFD. TFD represents the cumulative duration of all fixations in a given AOI; FC denotes the number of fixations within the AOI; and the MFD is calculated by dividing TFD by FC (Holmqvist et al., 2015; Hvelplund, 2014). At the sentence level, we focused only on the transcription side, where each page displayed 10 sentences of transcription. Each sentence was designated as an AOI, which resulted in 10 AOIs per transcription page. For these sentence-level AOIs we recorded the TFD, FC, MFD, and the first fixation timestamp on each sentence.

Figure 4

Delineation of area of interest

4.4.2 Temporal metrics

For the temporal metrics, we collected the ear–voice span (EVS) and the eye–voice span (IVS) at the sentence level. EVS was defined as the time interval between hearing information and the corresponding interpreting output, whereas IVS was the interval between seeing the information on-screen and interpreting it. Both metrics were marked at the beginning of each sentence and manually recorded using Elan 6.6[3] software. For IVS, the starting point was determined by the first fixation timestamp on each sentence, imported from Tobii Studio data.

4.4.3 Subjective data

The subjective data were gathered by means of a post-experiment questionnaire and a semi-structured interview. The online questionnaire[4] included standardized measures drawn from established usability and user experience frameworks: the System Usability Scale (SUS) (Brooke, 1996) to evaluate overall tool usability, the Computer System Usability Questionnaire (CSUQ) (Lewis, 1995) for utility assessment, the User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ) (Laugwitz et al., 2008) to gauge user experience, and the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis, 1989) to explore interpreters’ openness to CAI tools in SI. Additional questions covered the participants’ specific experiences with the tool and their preferences for future CAI developments, with detailed results to be presented in the following sections. Descriptive statistics were generated using the integrated data-analysis features of the online questionnaire platform. The semi-structured retrospective interview focused on the participants’ reflections and feedback about the CAI tool. Their responses were transcribed and analysed thematically to extract relevant insights relevant to our research questions.

The data analysis was performed using Python and also using libraries such as pandas and NumPy for data processing, SciPy and Statsmodels for statistical analysis, and matplotlib and seaborn for data visualization.

5. Results

The findings of this study are presented in three complementary sections: visual processing patterns observed through eye-tracking data; temporal synchronization metrics measuring the coordination between input and output; and subjective perceptions gathered through questionnaires and interviews. This integrated approach served to provide a comprehensive view of the ways in which interpreters interact with and experience automatic live captioning during SI.

5.1 Visual processing patterns

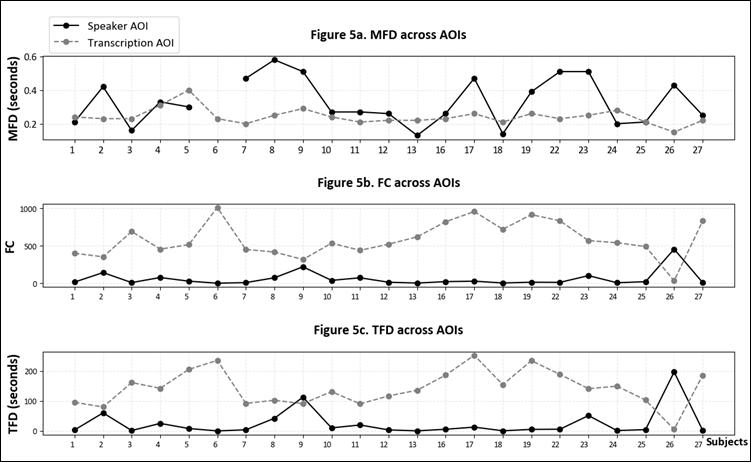

The eye-tracking data served as our primary source for investigating interpreter–CAI tool interactions during the SI workflow. Following the analysis approach outlined in the methodology, we first examine the fixation patterns at the global level (speaker vs transcription). Figure 5 presents the line plots comparing the MFD, FC, and TFD metrics across speaker and transcription AOIs. The black solid lines represent the metrics for the speaker AOI, whereas the grey dotted lines indicate the metrics for the transcription AOI. Note that Subject 6’s MFD data were treated as missing due to the complete absence of a speaker-directed gaze.

In Figure 5, we observe that the MFD is generally higher in the speaker AOI (M = 0.33, SD = 0.14) compared to the transcription AOI (M = 0.24, SD = 0.05), with 15 out of 22 valid MFD data points following this trend. This suggests that the participants spent longer fixating on the speaker than on the transcription. However, for both FC and TFD, the opposite pattern emerged. The transcription AOI had consistently higher FC (M = 584.78, SD = 243.91) compared to the speaker AOI (M = 59.04, SD = 101.55), except in the case of Subject 26. Similarly, the TFD for the transcription AOI (M = 142.54, SD = 58.98) exceeded that of the speaker AOI (M = 24.96, SD = 45.99), except for Subjects 9 and 26. The inverse relationship between FC and TFD across AOIs suggests a limited attention resource model, where increased attention to one channel necessarily reduces attention to the other. The combined fixation metrics indicate distinct viewing patterns across AOIs: shorter but more frequent fixations in the transcription AOI, contrasted with longer but less frequent fixations in the speaker AOI.

Figure 5

Mean fixation duration, fixation count, and total fixation duration across speaker and transcription AOIs

|

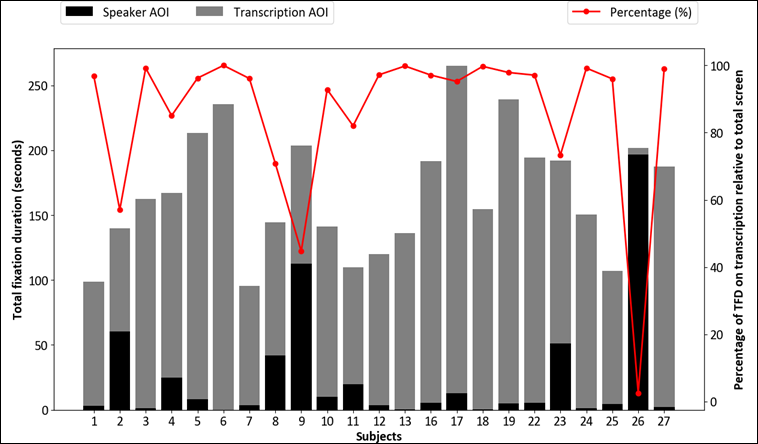

Further analysis of visual attention distribution through TFD allocation is presented in Figure 6, where stacked bars represent individual subjects’ TFD metrics (grey for speaker AOI, black for transcription AOI). The superimposed line plot indicates the percentage of TFD on transcription relative to total screen time. The data reveal a strong preference for transcription AOI, with 20 out of 23 subjects (86.96%) allocating more than 70% of their visual attention to this area. Only three subjects demonstrated lower transcription attention: Subject 2 (57.04%), Subject 9 (44.71%), and Subject 26 (2.52%). The mean transcription attention percentage of 85.10% indicates a pronounced preference for visual–verbal information processing.

Figure 6

Distribution of total fixation duration across speaker and transcription AOIs

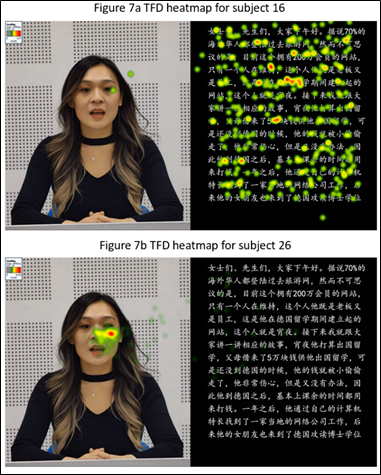

To illustrate these contrasting attention patterns in detail for the purpose of examination, Figure 7 presents TFD heatmaps generated by Tobii Studio for two representative subjects. The heatmaps employ a colour gradient from transparent through green and yellow to red, with increasing colour intensity indicating a longer fixation duration. Subject 16 exhibited a uniform distribution of fixations across the transcription AOI, with minimal attention being given to the speaker AOI; this suggests comprehensive use of visual–verbal information during SI. In contrast, Subject 26 concentrated their fixations almost exclusively on the speaker’s facial region, with minimal attention being given to the surrounding areas and negligible engagement with the transcription area; this indicates limited use of visual–verbal information during the SI process.

Figure 7

Comparison

of total fixation duration heatmaps for representative subjects

Whereas the global-level eye-tracking data reveal the ways in which interpreters allocate visual attention across the speaker and the transcription AOIs, the sentence-level analysis provides a more detailed view of the ways in which interpreters engage with the transcription content itself. Figure 8 illustrates the mean first fixation timestamp for all 23 subjects across ten sentences in each of the three pages (i.e. parts). The data reveal consistent scanning patterns across pages characterized by a predominantly forward progression at relatively uniform speeds.

Figure 8

Mean

first fixation time on sentences across pages

To explore this further, we calculated the time intervals between consecutive sentences on each page, defining the forward, skip, and backward reading patterns: a positive interval indicates forward progression, a negative interval indicates regression, and the absence of a value suggests a skip. Forward movements dominated the reading patterns across all the pages, with rates of 85.51%, 85.51%, and 76.33% for pages one, two, and three, respectively. Backward movements were less frequent, occurring at rates of 5.80%, 3.86%, and 9.66%, respectively, while skip rates were 8.70%, 21.26%, and 14.01% respectively. The aggregate pattern across all three pages indicated 82.45% forward movements, 6.44% backward movements, and 14.65% skips (SD = 0.19, 0.09, 0.18 respectively). The variation between individuals was considerable, with forward movement rates ranging from 0% to 100%, backward rates from 0% to 33%, and skip rates from 0% to 100%.

To examine the distribution of visual attention across all 30 sentences, we analysed the TFD, MFD, and FC for each sentence AOI using Linear Mixed Models (LMM). This analytical approach was selected for its robustness in dealing with the missing data and individual variations that commonly occur in eye-tracking studies. The models incorporated sentence position (1–30) as a fixed effect to account for content-specific variations in attention and subjects as random effects to cater for individual differences in processing styles. The model-fitting employed restricted maximum likelihood optimization to minimize bias in estimating the variance in random effects. All of the models demonstrated convergence, indicating a robust fit.

The LMM analyses revealed significant variations in visual processing across sentences. The FC analysis produced an estimated intercept of β = 19.261 (SE = 2.179, z = 8.839, p < 0.001, 95% CI: 14.990 to 23.532), with significant variations observed at multiple sentence positions, notably sentences 9, 15, 17, 20, 25, 28, and 29. Similarly, the MFD analysis revealed an estimated intercept of β = 5.309 (SE = 0.564, z = 9.410, p < 0.001, 95% CI: 4.203 to 6.415), with numerous sentences (2, 4, 6, 9, 15, 17, 20, 25, 28, and 29) demonstrating significantly lower values relative to the baseline. Particularly pronounced negative coefficients were observed in sentences 9, 15, 17, and 28. These data taken together indicate that some of these sentences consistently attracted fewer fixations. Regarding the MFD, the model yielded an estimated intercept of β = 0.266 (SE = 0.020, z = 13.394, p < 0.001, 95% CI: 0.227 to 0.305), with sentences 9, 15, 19, and 25 showing significantly lower values compared to the baseline; this suggests that these positions required less visual and cognitive engagement compared to the other sentences.

5.2 Temporal synchronization

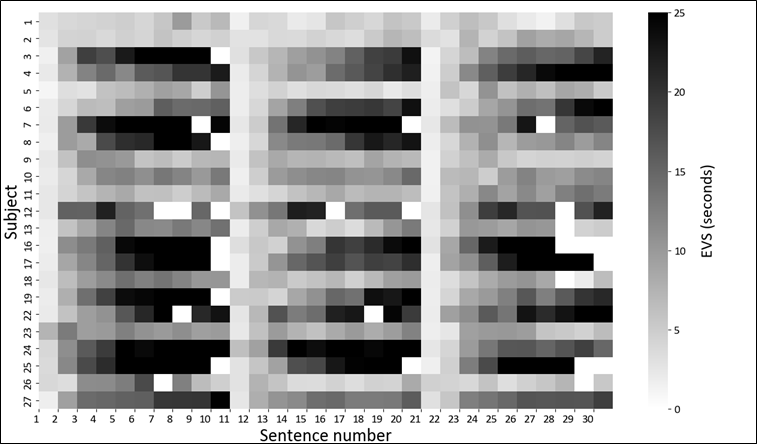

Whereas the eye-tracking data reveal the way interpreters allocate visual attention, temporal metrics such as EVS and IVS offer insights into the way interpreters synchronize auditory input, visual input, and verbal output; these metrics serve to highlight the coordination of inputs and outputs during the SI process. To analyse the EVS patterns, we plotted all the EVS data in a heatmap, as illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9

Heatmap of ear–voice spans across all sentences and subjects

|

In this figure, colour intensity corresponds to the EVS length, with darker shades representing longer EVS values. An EVS of 25 seconds or longer is represented in black, while missing data – instances where certain sentences were not interpreted by participants – are shown in white. The average EVS across all the participants was 12.22 seconds (SD = 5.36). Visual inspection of the heatmap suggests a general trend in which EVS increases towards the end of each page, which is indicated by progressively darker shades as sentences advance to the right.

To validate this observed pattern, we employed LMM analysis with EVS as the dependent variable, sentence position (1–10) and page number (1–3) as fixed effects, and subjects as random effects. The model, fitted using restricted maximum likelihood estimation, demonstrated full convergence. The results revealed a baseline EVS (intercept) of 5.286 seconds (SE = 1.657, p = 0.001). The position of a sentence emerged as a significant predictor of EVS (β = 1.733, SE = 0.200, z = 8.679, p < 0.001, 95% CI: 1.342 to 2.125), confirming that it increases systematically with an advance in sentence position. However, neither page number (β = –0.609, SE = 0.555, z = –1.098, p = 0.272, 95% CI: –1.697 to 0.478) nor the interaction between sentence position and page number (β = –0.105, SE = 0.092, z = –1.134, p = 0.257, 95% CI: –0.285 to 0.076) showed significant effects, indicating consistency in the EVS pattern across the pages.

Regarding the analysis of the IVS, we found an average IVS of 7.90 seconds (SD = 6.2), with both positive and negative values. A parallel LMM analysis of IVS patterns revealed no significant effects for sentence position (β = 0.561, SE = 0.429, z = 1.309, p = 0.190, 95% CI: –0.279 to 1.401), page number (β = 2.030, SE = 1.182, z = 1.717, p = 0.086, 95% CI: –0.288 to 4.347), or their interaction (β = –0.244, SE = 0.245, z = –0.994, p = 0.320, 95% CI: –0.725 to 0.237). These results indicate that there was no systematic evolution in the IVS values across the interpreting task.

Given the presence of both positive and negative IVS values, we also examined the distribution of these values. The analysis revealed a predominant tendency towards positive values, with positive IVS occurring in 74.35% of cases. The majority of the interpreters (20 out of 23, or 87%) demonstrated a clear preference for positive IVS, maintaining rates above 60%, although individual variation was substantial (range = 30–93%). Negative IVS patterns accounted for only 17.25% of instances, with missing data comprising the remaining 8.26%. This distribution suggests that the interpreters predominantly consulted the transcription tool before producing the outcomes of their interpreting instead of using it as a post-interpretation verification mechanism.

5.3 Interpreter experience and perceptions

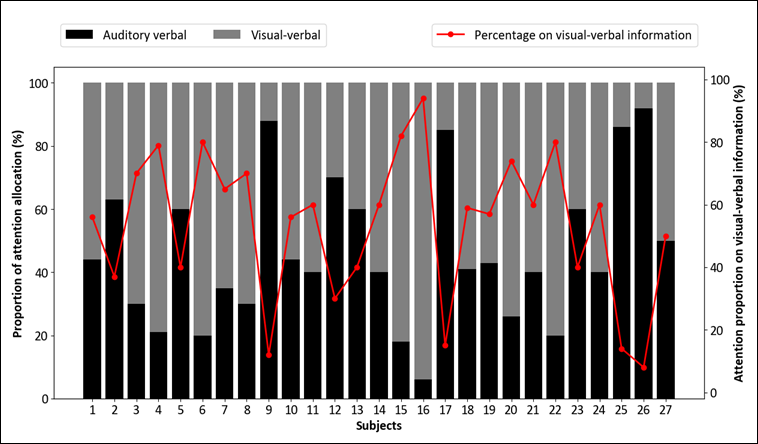

To supplement the objective data derived from the eye-tracking and the temporal metrics, subjective data were gathered by means of questionnaires and interviews. The participants reported their perceived attention allocation between visual–verbal information (transcription) and auditory–verbal information (audio). Figure 10 illustrates this distribution, with black bars representing attention to audio and grey bars showing attention to transcription.

Figure 10

Perceived proportion of attention allocation across speaker and transcription AOIs

The percentage of attention allocated to transcription varied considerably among the participants: it ranged from 8% (Subject 26) to 94% (Subject 16), with a mean of 53.63%.

Whereas 18 of the 27 participants reported allocating the majority of their attention to transcription, this number was lower than that observed in the eye-tracking data. Nevertheless, certain patterns were consistent across both the objective and the subjective measures. For instance, Subjects 9 and 26 demonstrated the lowest transcription attention allocation in both the eye-tracking data and the self-reported measures. Regarding their attention-allocation strategies, eight participants, including Subjects 9 and 26, reported deliberate strategic allocation, whereas the remaining 19 participants described their allocation as automatic behaviour.

An analysis of the participants’ experiences with the CAI tool revealed moderate satisfaction across multiple assessment metrics. The SUS yielded a mean score of 59.8 (SD = 14.0), indicating acceptable usability with room for improvement. The CSUQ produced a mean score of 4.70 (SD = 0.72) on a 7-point scale, suggesting above-moderate satisfaction with the quality of the information and the interface. The UEQ returned a mean score of 1.00 (SD = 0.84), indicating generally positive user perception while highlighting opportunities for improvement. The TAM assessment yielded a mean score of 3.79 (SD = 0.65) on a 5-point scale, demonstrating a moderately positive acceptance of CAI tool integration in the SI workflows.

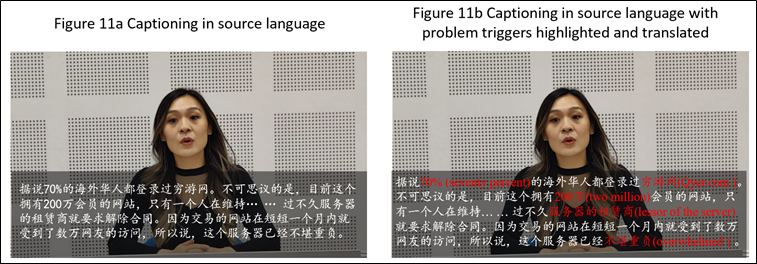

Regarding their future CAI tool preferences, computers emerged as the preferred device (56%), followed by tablets (22%), and telephones (12%). The display preferences showed a clear inclination towards captioning in the lower half of the screen (70%), with the remaining 30% favouring vertical positioning similar to that in the experimental setup. Their content preferences revealed that 77.8% of the participants (21 subjects) emphasized the importance of source speech transcription. In this group, 10 participants expressed an interest in integrated source language (SL) and the interpretation of problem triggers, similarly to the Cymo[5] tool interface presented in Figure 11b. Eight participants preferred source speech transcription alone (Figure 11a) whereas equal numbers (three participants each) favoured bilingual content, TL only, or problem trigger information exclusively.

Figure 11

Most preferred interfaces for CAI tools

|

The retrospective protocol interviews provided additional insights into the interpreters’ experiences with the CAI tool, revealing both perceived benefits and challenges. The interviews highlighted several key concerns regarding tool implementation. First, some interpreters reported difficulty in maintaining attention on audio input, suggesting a possible over-reliance on visual information. Secondly, the availability of a complete source text appeared to create pressure to include more information in the interpreting, sometimes resulting in an increase in lag behind the speaker. Thirdly, the participants expressed their concern that transcription errors – particularly those made when they were processing accented speech – could possibly mislead interpreters and lead to interpreting failures. This suggests that over-reliance on the tool during accent-heavy speeches could be problematic.

Despite these challenges, the majority of the participants characterized the CAI tool as being largely beneficial. A primary advantage emerged in dealing with the structural disparities between Chinese and English. The interpreters noted that the significant syntactical differences between these languages typically demand substantial cognitive resources to re-organize the content in real-time. The visual presentation of the source text served as a cognitive scaffold, reducing their working memory load and facilitating more efficient syntactic restructuring for the production of the target language.

The function of the transcription tool as a cognitive support mechanism emerged as a recurring theme. The interpreters described using the visual text strategically to enhance both their interpretation speed and their accuracy. In addition, many of the participants emphasized the role of the tool as a reliability safeguard. Moreover, the presence of visual text appeared to increase interpreter confidence, particularly during challenging segments, by providing a verification mechanism with which to maintain accuracy and consistency.

6. Discussion

6.1 Patterns of interaction with live captioning: visual and temporal insights

The integration of live captioning into SI highlights the complex interaction patterns between interpreters and this tool, responding to our first research question. Our empirical data yielded several findings regarding these patterns of interaction.

First, the interpreters demonstrated a pronounced dependency on live captioning as a primary source of information, showing a strong visual–verbal focus. The eye-tracking data indicate that the participants devoted 85.10% of their TFD to the transcription AOI, while self-reported data indicate that the interpreters perceived dedicating 53.63% of their attention to the visual–verbal channel. This finding aligns with those of previous studies (e.g. Chmiel et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020; Zou et al., 2022) which indicate that, in SI tasks involving textual input, interpreters tend to prioritize visual input. Furthermore, this trend corroborates research on SI with live captioning (Yuan & Wang, 2023). Nevertheless, substantial individual variation was observed, such as with Subject 6 (100% reliance on live captioning) and Subject 26 (2.52% reliance), which emphasizes the importance of considering individual differences in analysing SI performance.

Secondly, live captioning appears to contribute to an increase in interpreting delays. The EVS showed significant progression as the sentence sequences advanced independently of the page content; this suggests that this pattern stems from behavioural rather than content-dependent factors. The scale of the delay is striking: the mean EVS in the present study is roughly 12 seconds – well above the 5–7 seconds reported by Chang (2009) and the ≈3 seconds reported by Yang et al. (2020) for Mandarin‑to‑English student interpreters. Moreover, the interview data corroborate this finding, with the participants reporting feeling compelled to interpret all the information present in the transcription. This phenomenon mirrors observations in SI with text, where Gile (2009) noted that the availability of complete textual information often leads interpreters to attempt comprehensive translation, even when the speech delivery exceeds manageable speeds.

Thirdly, cognitive effort, as inferred from the MFD, fluctuates notably during SI with live captioning. The MFD is widely considered to be an indicator of cognitive effort, where higher MFD values suggest increased cognitive effort (Korpal & Stachowiak-Szymczak, 2018; Han et al., 2024). Higher MFD values on the speaker compared to the transcription suggest greater cognitive effort when attending to the speaker. Whereas Han et al. (2024) attributed similar findings to the requirements of manual interactions, our study involved minimal speaker movement and no manual operations. We propose that an elevated MFD during speaker fixations may reflect the combined processing of both visual and auditory information. Our findings for the MFD in the transcription AOI (0.24 seconds) align remarkably with those reported by Prandi (2023), who observed a comparable MFD (0.25 seconds) when the participants interacted with a simulated ASR-based terminology-suggestion tool. This similarity suggests that cognitive processing patterns are consistent when interpreters engage with automatically generated textual content. In addition, significant variations in the MFD across different sentences suggest a content-dependent cognitive effort that is consistent with Korpal and Stachowiak-Szymczak’s (2018) findings.

The eye-movement patterns tend to indicate that interpreters typically process visual information before producing the outcomes of interpreting, suggesting the effective integration of live captioning into the SI workflow. The participants generally exhibited linear reading patterns at the sentence level, displaying evidence of only limited backward saccades and skipping behaviour. However, substantial individual variations in their processing styles were observed, indicating that they adopted diverse approaches to managing the visual input during SI.

6.2 User experience and evaluation of live captioning integration in SI

The assessment of the interpreter trainees’ perceptions of the integration of live captioning in SI revealed two key findings. First, based on the TAM analysis, the trainees demonstrated a positive willingness to incorporate CAI tools into their future professional practice. Secondly, while automatic live captioning received favourable ratings for its usability and utility, the moderate levels of satisfaction suggest areas for improvement. This evaluation gains particular relevance as automatic captioning becomes increasingly embedded in contemporary conferencing platforms.

An analysis of user preferences revealed specific requirements for optimal CAI tool design. The participants largely favoured computer-based CAI software that displays SL transcription with problem triggers highlighted and their corresponding automatic translations presented as captions in the lower screen area with high precision and minimal latency. Notably, only 11% of the participants preferred displays that are limited to problem triggers alone; this finding contrasts with those of previous research (EABM, 2021; Frittella, 2023; Prandi, 2023).

This preference for continuous transcription over problem-trigger-only displays can be attributed to several factors. First, as seen in Frittella’s study (2023), the exclusive display of problem triggers led to an increase in errors beyond the scope of individual problem triggers, which suggests that an isolated focus on problem areas may disrupt the interpreter’s natural cognitive flow, resulting in fragmented output. Continuous transcription, in contrast, facilitates a seamless interpreting process, reducing the risk of cognitive disruptions and supporting a more cohesive delivery.

Furthermore, the research by Seeber et al. (2020) on professional interpreters working with text in SI contexts reveals that continuous text helps to manage the cognitive load by easing the demands on working memory – a critical element in interpreting. These findings align with Gile’s Effort Model (2009), which posits that, for effective interpreting to occur, the requirements of total processing capacity must not exceed the available capacity. Continuous transcription may help to optimize the allocation of cognitive resources by reducing the demands on working memory, possibly increasing the overall processing capacity and enhancing performance. This perspective suggests that CAI tools should expand beyond their traditional focus on terminology and numeric support to include features that facilitate broader cognitive management during interpreting.

6.3 Implications for interpreting practice

The integration of CAI tools in SI renders it necessary to devote attention to both interpreter adaptation and tool optimization. As for the cognitive implications, our findings indicate that interpreters tend to over-rely on CAI tools, possibly compromising their interpreting efficiency. The subjective questionnaire data reveal that most of the participants engaged with the tool automatically rather than strategically. However, Subject 26’s experience – deliberately minimizing attention to transcription after discovering its distracting effects during practice – demonstrates the feasibility of managing conscious attention. This suggests that interpreter training should incorporate both the use of strategic tools and attention-management exercises in order to optimize the integration of CAI tools. From a technological perspective, our study confirms that automatic live captioning, despite its not being specifically designed for interpreting, shows promise as a CAI tool and generally receives positive user acceptance. The preferred features identified by the trainee interpreters – including customizable interfaces and continuous transcription – provide valuable insights for the development of tools.

This study has several limitations that should qualify its conclusions. First, the participant pool was small (n = 27) and overwhelmingly female, which precludes any systematic assessment of gender effects and leaves a feminist technology perspective under-represented. Future work should employ stratified sampling that deliberately balances gender and adopts feminist technology frameworks in determining whether sex-based or gendered strategy preferences modulate cognitive engagement with CAI tools and users’ evaluations of them. Secondly, although the questionnaire clarifies why participants consulted the live transcript, the study did not analyse whether this reliance altered their use of other interpreting strategies – such as anticipation, compression, paraphrase, or note‑taking. As a result, the broader reconfiguration of the SI technique repertoire remains unexplored. Future research should combine eye‑tracking with detailed strategy coding in order to determine the extent to which the use of transcripts shifts interpreters’ deployment of other compensatory techniques. Finally, this article reports only on the quantitative eye‑tracking and timing data; the accompanying qualitative performance and interview analyses are presented in a separate manuscript.

7. Conclusion

This study investigated the integration of automatic live captioning into the SI workflow. It focused on interpreters’ interactions with and perceptions of live captioning through a triangulated quantitative analysis of eye-tracking data, temporal metrics, and user feedback. Our findings suggest that live captioning (the “sight” in our title) significantly influences interpreters’ engagement patterns and cognitive processes (the “insight” in our title), with student interpreters showing a strong reliance on visual transcription and positioning the text as a primary support mechanism in the SI workflow. This integration affects the timing of interpreting, with progressive increases in EVS observed during tasks, indicating challenges in information management when interpreting with live captioning. These findings underscore the need for strategic approaches to tool use in SI in order to mitigate a possible cognitive overload and manage pacing effectively.

The implications of this research extend to both interpreter training and CAI tool development. In training, the observed tendency for interpreters to engage instinctively with transcription resources suggests a need for targeted modules on strategic CAI usage. These modules should emphasize the need for controlled engagement with live captioning and the integration of attention-management techniques to balance the focus between visual and auditory channels. Regarding CAI development, our results support the ongoing integration of live captioning features, highlighting the importance of customizable interfaces that account for individual differences in processing styles and interpreter preferences.

This study contributes to the understanding of the integration of CAI tools into SI, especially the role of live captioning in supporting interpreters. As the field advances, adopting a balanced approach to CAI integration – grounded in empirical evidence and aligned with interpreters’ cognitive workflows – will be essential to fostering seamless, effective applications of technology in professional interpreting practice. These findings also resonate with ongoing shifts aimed at enabling more collaborative human–technology dynamics in interpreting; these shifts reflect broader trends in the evolving technological landscape of the profession. Future research should continue to examine individual differences in strategy use and the possible impact of user demographics such as gender on interpreters’ interactions with tools and their performance outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities in the University of International Business and Economics under Grant [24QD32].

References

Brooke, J. (1996). SUS: A “quick and dirty” usability scale. In P. W. Jordan, B. Thomas, I. L. McClelland, & B. Weerdmeester (Eds.), Usability evaluation in industry (pp. 189–194). CRC Press.

Cammoun, R., Davies, C., Ivanov, K., & Naimushin, B. (2009). Simultaneous interpretation with text: Is the text “friend” or “foe”? Laying foundations for a teaching module [Seminar paper]. University of Geneva.

Chang, A. L. (2009). Ear-voice-span and target language rendition in Chinese to English simultaneous interpretation. 翻譯學研究集刊(Studies of Translation and Interpretation), 12, 177–217. https://doi.org/10.29786/STI.200907.0006

Cheung, A. K. F., & Li, T. (2022). Machine-aided interpreting: An experiment of automatic speech recognition in simultaneous interpreting. Translation Quarterly, 104, 1–20.

Chmiel, A., Janikowski, P., & Lijewska, A. (2020). Multimodal processing in simultaneous interpreting with text. Target, 32(1), 37–58. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.18157.chm

CSA Research. (2017). CSA research survey on gender and family in the language services industry: Overall findings. https://csa-research.com/Blogs-Events/CSA-in-the-Media/Press-Releases/Impact-of-Gender-and-Family-in-the-Global-Language-Services-Industry

Cui, Y., & Zheng, B. (2021). Consultation behaviour with online resources in English–Chinese translation: An eye-tracking, screen-recording and retrospective study. Perspectives, 29(5), 740–760. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2020.1760899

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

Defrancq, B., & Fantinuoli, C. (2021). Automatic speech recognition in the booth: Assessment of system performance, interpreters’ performances and interactions in the context of numbers. Target, 33(1), 71–102. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.19166.def

Desmet, B., Vandierendonck, M., & Defrancq, B. (2018). Simultaneous interpretation of numbers and the impact of technological support. In C. Fantinuoli (Ed.), Interpreting and technology (pp. 13–27). Language Science Press.

EABM. (2021). Survey: Ergonomics for the artificial booth mate (EABM). https://www.eabm.ugent.be/survey/

Fantinuoli, C. (2017). Speech recognition in the interpreter workstation. Translating and the Computer 39 (pp. 10). ASLING. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321137853_Speech_Recognition_in_the_Interpreter_Workstation

Fantinuoli, C. (2018). Computer-assisted interpreting: Challenges and future perspectives. In G. Corpas Pastor & I. Durán Muñoz (Eds.), Trends in e-tools and resources for translators and interpreters (pp. 153–174). Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004351790_009

Fantinuoli, C. (2023). Towards AI-enhanced computer-assisted interpreting. In G. Corpas Pastor & B. Defrancq (Eds.), Interpreting technologies: Current and future trends (Vol. 37, pp. 46–72). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/ivitra.37.03fan

Fantinuoli, C., & Dastyar, V. (2022). Interpreting and the emerging augmented paradigm. Interpreting and Society: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 2(2), 185–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/27523810221111631

Fantinuoli, C., & Prandi, B. (2018). Teaching information and communication technologies: A proposal for the interpreting classroom. Journal of Translation and Technical Communication Research, 11(2), 162–182.

Frittella, F. M. (2023). Usability research for interpreter-centred technology. Language Science Press.

Gile, D. (2009). Basic concepts and models for interpreter and translator training (Rev. ed.). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.8

Guo, M., Han, L., & Anacleto, M. T. (2023). Computer-assisted interpreting tools: Status quo and future trends. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 13(1), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.17507/tpls.1301.11

Guo, M., Han, L., & Li, D. (2024). Computer-assisted interpreting in China. In R. Moratto & C. Zhan (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of Chinese interpreting (pp. 439–452). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781032687766-36

Han, C., & Lu, X. (2021). Interpreting quality assessment re-imagined: The synergy between human and machine scoring. Interpreting and Society, 1(1), 70–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/27523810211033670

Han, C., Zheng, B., Xie, M., & Chen, S. (2024). Raters’ scoring process in assessment of interpreting: An empirical study based on eye tracking and retrospective verbalisation. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 18(3), 400–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2024.2326400

He, Y., Sainath, T. N., Prabhavalkar, R., McGraw, I., Alvarez, R., Zhao, D., Rybach, D., Kannan, A., Wu, Y., Pang, R., Liang, Q., Bhatia, D., Shangguan, Y., Li, B., Pundak, G., Sim, K. C., Bagby, T., Chang, S., Rao, K., & Gruenstein, A. (2019). Streaming end-to-end speech recognition for mobile devices. IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), UK, 6381–6385. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICASSP.2019.8682336

Holmqvist, K., Nystrom, M., Andersson, R., Dewhurst, R., Jarodzka, H., & Weijer, J. V. D. (2015). Eye tracking: A comprehensive guide to methods and measures (Reprint). Oxford University Press.

Hvelplund, K. T. (2014). Eye tracking and the translation process: Reflections on the analysis and interpretation of eye-tracking data. MonTI, 1, 201–223. https://doi.org/10.6035/MonTI.2014.ne1.6

Jurafsky, D., & Martin, J. H. (2024). Speech and language processing: An introduction to natural language processing, computational linguistics, and speech recognition with language models (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall.

Korpal, P., & Stachowiak-Szymczak, K. (2018). The whole picture: Processing of numbers and their context in simultaneous interpreting. Poznan Studies in Contemporary Linguistics, 54(3), 335–354. https://doi.org/10.1515/psicl-2018-0013

Laugwitz, B., Held, T., & Schrepp, M. (2008). Construction and evaluation of a user experience questionnaire. In A. Holzinger (Ed.), HCI and usability for education and work (pp. 63–76). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-89350-9_6

Lewis, J. R. (1995). IBM computer usability satisfaction questionnaires: Psychometric evaluation and instructions for use. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 7(1), 57–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447319509526110

Li, C. (2010). Coping strategies for fast delivery in simultaneous interpretation. The Journal of Specialised Translation, 13, 19–25. https://doi.org/10.26034/cm.jostrans.2010.604

Li, T., & Fan, B. (2020). Attention-sharing initiative of multimodal processing in simultaneous interpreting. International Journal of Translation, Interpretation, and Applied Linguistics, 2(2), 42–53. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJTIAL.20200701.oa4

Olsen, A. (2012). The Tobii I-VT fixation filter. Tobii Technology, 21(4–19), 5.

Pöchhacker, F. (2016). Introducing interpreting studies (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1556/084.2023.00607

Prandi, B. (2020). The use of CAI tools in interpreter training: Where are we now and where do we go from here? inTRAlinea, Special Issue.

Prandi, B. (2023). Computer-assisted simultaneous interpreting: A cognitive-experimental study on terminology. Language Science Press.

Riccardi, A., Čeňková, I., Tryuk, M., Maček, A., & Pelea, A. (2020). Survey of the use of new technologies in conference interpreting courses. In M. D. R. Melchor, I. Horváth, & K. Ferguson (Eds.), The role of technology in conference interpreter training (pp. 7–42). Peter Lang.

Saeed, M. A., González, E. R., Korybski, T., Davitti, E., & Braun, S. (2022). Connected yet distant: An experimental study into the visual needs of the interpreter in remote simultaneous interpreting. In M. Kurosu (Ed.), Human–computer interaction: User experience and behavior (pp. 214–232). Springer International. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-05412-9_16

Seeber, K. G. (2017). Multimodal processing in simultaneous interpreting. In J. W. Schwieter & A. Ferreira (Eds.), The handbook of translation and cognition (pp. 461–475). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119241485.ch25

Seeber, K. G., Keller, L., & Hervais-Adelman, A. (2020). When the ear leads the eye: The use of text during simultaneous interpretation. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 35(10), 1480–1494. https://doi.org/10.1080/23273798.2020.1799045

Wan, H., & Yuan, X. (2022). Perceptions of computer-assisted interpreting tools in interpreter education in China’s mainland: Preliminary findings of a survey. International Journal of Chinese and English Translation & Interpreting, 1, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.56395/ijceti.v1i1.8

Will, M. (2020). Computer-aided interpreting (CAI) for conference interpreters: Concepts, content and prospects. ESSACHESS: Journal for Communication Studies, 13(1(25)), 37–71.

Yang, S., Li, D., & Lei, V. L. C. (2020). The impact of source text presence on simultaneous interpreting performance in fast speeches: Will it help trainees or not? Babel, 66(4–5), 588–603. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.00189.yan

Yuan, L., & Wang, B. (2023). Cognitive processing of the extra visual layer of live captioning in simultaneous interpreting: Triangulation of eye-tracking and performance data. Ampersand, Article 100131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amper.2023.100131

Yuan, L., & Wang, B. (2024). Eye-tracking the processing of visual input of live transcripts in remote simultaneous interpreting: Preliminary findings. FORUM, 22(1), 119–145. https://doi.org/10.1075/forum.00038.yua

Zou, L., Carl, M., & Feng, J. (2022). Patterns of attention and quality in English–Chinese simultaneous interpreting with text. International Journal of Chinese and English Translation & Interpreting, 2, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.56395/ijceti.v2i2.50