Multimodal input in computer-assisted simultaneous interpreting: Effects on interpreting quality, cognitive load, and attention dynamics

Xuejiao Peng

Hunan University, China

http://orcid.org/0009-0003-9284-7187

Xiangling Wang

Hunan University, China

xl_wang@hnu.edu.cn

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8889-7569

Guangjiao Chen

Hunan University, China

cguangjiao@163.com

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8767-1645

Abstract

Computer-assisted simultaneous interpreting (CASI) is increasingly exposing interpreters to multimodal digital environments by means of added visual input. Yet little is known about how multimodal text and speaker inputs affect overall interpreting quality, cognitive load, and attention dynamics. Drawing on analyses of quality assessment, self-reported questionnaires, and eye-tracking data, this study compared CASI with conventional SI regarding the effects on overall interpreting quality, cognitive load, and attention dynamics. In it, 30 student interpreters performed simultaneous interpreting (SI) from English to Chinese across four input conditions: audio-only, audio–video, audio–text, and audio–video–text. The results indicate that the visual input provided by CASI tools significantly improved their interpreting quality and reduced their cognitive load; moreover, the audio–video–text CASI condition yielded the highest interpreting quality and a relatively low cognitive load. In addition, the student interpreters strategically adjusted their attention across different visual input conditions. When audio, video, and text inputs were available concurrently, they prioritized textual input over both auditory cues and speaker video and demonstrated distinct patterns of strategic coordination. In this article, the theoretical, practical, and pedagogical implications of these findings are discussed.

Keywords: computer-assisted simultaneous interpreting; CASI; multimodal input; cognitive load; interpreting quality; attention division; attention coordination

1. Introduction

As a highly complex cognitive activity, simultaneous interpreting (SI) manifests inherent multidimensional complexity that is the product of both multitasking operations and multimodal information processing. This is because, on the one hand, SI tasks require interpreters to engage in the continuous parallel processing of multiple cognitive subtasks that encompass listening, memory, production, self-monitoring, and the coordination of cognitive resources (Gile, 2009; Lederer, 1981; Seeber, 2011; Setton, 1999). On the other, interpreters are required to construct cross-modal meaning representations dynamically by selecting, extracting, integrating, and processing multisource information in real-time; such information is likely to include verbal, paraverbal, and nonverbal cues and contextual parameters (Seeber, 2017; Wang, 2023). The inherent temporal overlap in multitasking operations may induce cognitive interference, which could present an intrinsic challenge; this interference raises interpreters’ susceptibility to external visual stimuli and information overload, in this way possibly exacerbating their cognitive load during multimodal information processing (Seeber, 2011). Interestingly, practitioners demonstrate a marked preference for incorporating additional visual inputs over engaging in “pure” SI while maintaining consistent performance metrics (Mackintosh, 2003).

The inherent complexity of SI tasks, coupled with the recent advancements in interpreting-related technologies, has positioned computer-assisted interpreting (CAI) as a promising solution to enhancing SI quality and productivity. According to Fantinuoli (2018a), CAI is

a form of oral translation wherein a human interpreter makes use of computer software developed to support and facilitate some aspects of the interpreting task with the overall goal to increase quality and productivity.

In this study, we were interested in investigating computer-assisted simultaneous interpreting (CASI) in which computer programs are developed specifically to aid interpreters in one or more sub-processes of SI. CASI tools have evolved from simple glossary creation and management systems to multifunctional workstations. Recent advancements have seen these tools integrate sophisticated remote simultaneous interpreting (RSI) platforms and artificial intelligence-powered capabilities, including automatic speech recognition (ASR) and machine translation (MT) (Fantinuoli, 2023). This technological evolution is fundamentally transforming the input environment of SI. A noteworthy feature of contemporary CASI tools is their textual representation of source speech signals. Equipped with digital glossaries or ASR system configurations, these tools extend interpreters’ working memory (Mellinger, 2023) by introducing supplementary visual information; in this way they create enriched multimodal digital ecosystems for use in professional practice.

The increasing role that technologies are playing in SI practice is partly attributable to the belief that the multimodal input provided by CASI tools (e.g., terminology support) has the potential to enhance interpreters’ comprehension of source texts, reduce short-term memory load (Gile, 2009), and free up those cognitive resources specifically dedicated to target-language production. However, two critical risks exist: information discrepancies and cognitive load induced by cross-modal interference and redundancy. First, there may be discrepancies between the system outputs (e.g., transcriptions or term suggestions) and the speaker’s actual words due to speech-recognition errors (Li & Chmiel, 2024) or inaccurate retrievals from the corpus. The possible information discrepancies force interpreters to monitor the consistency between auditory input and visual cues continuously, which requires split-second decisions to be made about whether to adopt system-generated suggestions or not. Secondly, the visual support of CASI tools may create information redundancy and interference that increase an interpreter’s cognitive load. On the one hand, compared to pure SI, the concurrent presence of information from both auditory and visual channels is likely to generate more redundancy and impose additional cognitive load on a practitioner’s working memory (Kalyuga & Sweller, 2014). On the other, the interference stemming from cross-modal temporal asynchrony (Seeber et al., 2020) – specifically, the time lag between visual decoding and auditory input – induces additional cognitive load because of the necessity of suppressing such interference. These variables may jeopardize interpreters’ ability to coordinate their attention, increase their working memory load (Kalyuga & Sweller, 2014), and drain the cognitive resources that would otherwise be allocated to processing critical elements (e.g., paraverbal and contextual cues). The effect would be to increase substantially the cognitive complexity of the CASI process.

Given the inherent complexity of CASI, empirical enquiries into the cognitive challenges posed by multimodal input are of practical, pedagogical, and theoretical significance in facing the technological turn (Fantinuoli, 2018b). A better understanding could provide empirical data with which stakeholders would be able to refine the design of CASI tools, provide insights into better-informed interpreter training and interpreting practice, and offer more empirical evidence for the development of interpreting models and theories that incorporate the use of technology.

Earlier studies have demonstrated the promising performance of textual input in facilitating numerical accuracy in CASI (Defrancq & Fantinuoli, 2021; Desmet et al., 2018); however, the efficacy of other visual inputs, such as the visibility of the speaker, remains unclear in CASI. Furthermore, the impact of multimodal input on overall interpreting quality, cognitive load, and attention dynamics in CASI has received limited attention. Therefore, the goal of the present study was to investigate the influence of multimodal input on CASI – including both text availability and the speaker’s visibility. With that goal in mind, the study compared student interpreters’ overall interpreting quality, cognitive load, and attention division and coordination across four different input conditions.

2. Literature review

The influence of multimodal input on CASI has seldom been explored explicitly, but it has been alluded to implicitly in previous research. Three contentious questions have arisen in previous studies regarding the impact of multimodal input in CASI. The first and most prolific question concerns whether visual aids provided by CASI tools can enhance the quality of SI. The second question centres on whether such multimodal input might reduce interpreters’ cognitive load. The third debate explores the impact of multimodal input on interpreters’ attention dynamics – in other words, attention division and coordination – during CASI tasks.

The impact of CASI tool usage on SI quality is one of the most extensively researched aspects of interpreting. The usefulness of CASI tools in dealing with numbers and terminology in SI has been investigated by some (Defrancq & Fantinuoli, 2021; Desmet et al., 2018; Li & Chmiel, 2024; Pisani & Fantinuoli, 2021). These studies, which employed distinct aiding approaches (e.g., displaying numbers in isolation or embedded within transcriptions), found that the accuracy of number renditions improved significantly. For example, Desmet et al. (2018) conducted a pilot study in which student interpreters used a simulated CAI tool integrated with ASR to display a visual version of the numbers on the screen. They found that the accuracy of the interpreted numbers improved by approximately from 56.5% to 86.5%. In a follow-up experiment carried out by Defrancq and Fantinuoli (2021), they investigated the usefulness of the InterpretBank ASR tool that provides a transcript with the numbers highlighted for student interpreters. The study also observed that the provision of ASR enhanced the level of accuracy for all number types.

Studying accuracy from a slightly different perspective, Li and Chmiel (2024) examined the effect of ASR-generated real-time subtitles on interpreting accuracy. They found that the presence of subtitles significantly improved accuracy for critical items such as proper nouns, numbers, and content words, regardless of the subtitle precision rate. Similar results have also been reported in the research of Pisani and Fantinuoli (2021), whose study employed automatically recognized numbers displayed in isolation, and that of Prandi (2015), which involved term-searching configurations. However, the generalizability of these studies is limited due to the experimental findings being based only on the accuracy of numbers or terminology. The ways in which CAI tools affect overall SI quality therefore remain unclear. Few studies have focused on the impact of CAI tool usage on overall SI quality, except for those of Frittella (2022, 2023) and Prandi (2023). Frittella (2023) conducted a holistic analysis of interpreting performance (the sentence, the coherence and cohesion of the speech passage, etc.) and found that even when individual items were rendered correctly, a considerable percentage of errors were found beyond the scope of the problem trigger. This suggested that CAI usage may result in an overall inaccurate delivery. Prandi (2023) compared ASR-CAI tools against manual terminology lookup (using digital glossaries and standard CAI tools) and found that ASR-CAI improved both the accuracy of terms and the quality of the contextual rendering in SI.

Beyond interpreting quality, cognitive load is another critical consideration (Chen & Kruger, 2023; Mellinger, 2019, 2023), because CASI tools can be considered really effective only if the resulting improvement in interpreting quality outweighs the cognitive load required to use them. Seeber’s (2011, 2017) discussion on multimodal input in SI provides a valuable reference for understanding the impact of multimodal input in CASI. According to Seeber’s cognitive footprint matrix, the interference score or, in other words, the cognitive load, increases with the modality of the input from different channels – increasing from 9 (audio-only) to 11.6 (with visual–spatial information) and further to 14.8 (with both text and speaker visibility). Prandi (2018) also applied this framework to analyse the cognitive load in CASI and hypothesized, based on the model, that manual terminology lookup (digital glossaries and standard CAI tools) would require a higher cognitive load than ASR tools (Prandi, 2023). By employing a multi-method approach, Prandi (2023) found that ASR-CAI is able to reduce significantly the cognitive load during interpreting. Although previous investigations have involved limited sample sizes, their methodological approaches yielded valuable insights that informed our research framework. Moreover, Chen and Kruger (2024) observed a reduced cognitive load among student interpreters who received ASR transcripts paired with machine-generated translations. This followed Cheung and Li’s (2022) study, which indicated enhanced psychological security for interpreters processing ASR-derived subtitles in real-time during SI tasks. Drawing on self-reporting, eye-tracking, and EEG data, Li and Chmiel’s (2024) investigation involving professional interpreters also demonstrated that employing ASR subtitles alleviates cognitive load.

In order to gain a better understanding of the cognitive impact of multimodal input in CASI, research into interpreters’ attention division and coordination is therefore necessary. Defrancq and Fantinuoli (2021) investigated the experiences and interactions of six student interpreters with ASR support during SI in a booth using a camera and a questionnaire. The findings indicate that the participants engaged with the ASR support in diverse ways, consulting it in more than half of the experimental stimuli. The study also demonstrated that ASR support, whether actively used or not, significantly improved the accuracy of numerical interpreting, which suggests that there are psychological benefits. However, when ASR support was temporarily unavailable, complete rendition rates dropped from the supported baseline (94.9%) to merely 50% – even lower than the rate in the unsupported booths (69.1%) – which indicated an over-reliance on ASR support. Similar findings were reported by Frittella (2023), who tested the usability of the ASR and the AI-powered CAI tool SmarTerp and noted that even professional interpreters showed a tendency towards indiscriminate reliance on CAI support and struggled to achieve a balance between reliance and autonomy. In addition, it was noted that interpreters often failed to attend to the acoustic input and to grasp the overall meaning of a message, a finding that aligns with the observations of Prandi (2015). In a more relevant study, Li and Chmiel (2024) found that professional interpreters devoted significantly longer visual attention to subtitles than to the speaker’s area across varying levels of ASR precision.

Taken together, the existing studies, while providing valuable insights, have focused primarily on isolated term accuracy. As a result, they have paid limited attention to the way multimodal input may affect interpreting quality at the global level and other equally important aspects, including cognitive load and attention division and coordination. Moreover, previous research has predominantly focused on textual input (e.g., comparing scenarios with versus without visual–verbal support), leaving the speaker’s visibility – a typical element of multimodal input in SI – under-researched. Given that speaker visibility may influence interpreters in real-world settings (Bühler, 1985; Peng et al., 2024; Rennert, 2008; Setton & Dawrant, 2016a; Shang & Xie, 2024), it would be beneficial to incorporate this factor in order to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the way in which multimodal input shapes cognitive processing during CASI.

3. The present study

This study aimed to investigate the influence of multimodal input (the text and the speaker) on student interpreters’ overall interpreting quality, cognitive load, and attention division and coordination in CASI. In order to gain a greater understanding of the impact of multimodal input on CASI, four experimental conditions were created to simulate the input conditions: audio-only, audio–video, audio–text, and audio–video–text. The audio-only condition mirrors typical interpreting classroom exercises or accreditation test procedures administered in China (Shang & Xie, 2024). The second input condition replicates conventional SI parameters: speaker visibility without supplemental text. The first two input conditions served as a baseline for our analysis. The third and fourth conditions simulate ASR-CASI with and without speaker visibility. Because this article focuses on state-of-the-art ASR-supported CASI tools, we examined this form of aiding exclusively, setting aside alternative assistance methods. Nevertheless, the authors acknowledge the importance of empirically evaluating diverse approaches and configurations to determine their cognitive impact on SI and to identify the conditions under which they achieve optimal outcomes. To understand multimodality in CASI better, a mixed-methods approach containing audio recording, eye tracking, and interviews was employed to collect data from a group of student interpreters while they were performing SI from English to Chinese under four different input conditions. The study attempted to respond to the following questions:

(1) How does the overall interpreting quality compare across audio-only, audio–video, audio–text, and audio–video–text conditions?

(2) How does the cognitive load compare across audio-only, audio–video, audio–text, and audio–video–text conditions?

3.1 Participants

Thirty master’s-level student interpreters from four universities in China were recruited, including 23 females and seven males, aged between 22 and 27 (SD = 1.3). They are all native Chinese speakers with English as their L2. They have similar levels of English proficiency, as they had all passed the entrance examination for the Master of Translation and Interpreting (MTI) programme and had passed the China Accreditation Test for Translators and Interpreters (CATTI) in the English–Chinese language pair or gained the English Proficiency Test for English Majors Band 8 (TEM8). During the participant recruitment, all of them confirmed that they had received intensive professional SI training for one semester (16 weeks). The results of the pre-questionnaire indicate that none of the participants had had any professional experience in interpreting. They were rewarded 40 yuan for their valuable time spent completing the tasks.

3.2 Materials

We selected four speeches, each on a different topic, from the European Union’s speech repository (European Commission, 2012a, 2012b, 2017, 2019). For pedagogical purposes, the speeches featured plain language and had a clear logical structure. Their duration remained consistent with the participants’ routine training parameters. Multiple validation protocols were implemented to ensure the comparability of the materials. First, the speeches were all pitched at the intermediate level in the corpus. Secondly, parameters ensuring the comparability of the stimuli were checked. These included the duration, speed, word count, readability level,[1] proposition count (Brown et al., 2008),[2] and idea density[3] (Table 1). The second speech underwent controlled rate modification with preserved articulation parameters to ensure its comparability. To ensure that the difficulty of the experimental materials was appropriate to the participants of this study, four MTI graduates at a level comparable to that of the participants were invited to assess the level of difficulty of the stimuli further. A nine-point Likert scale (Paas, 1992) was used for this purpose, with 1 being “extremely easy” and 9 being “extremely difficult”. The results showed that the four speeches were comparable.

Table 1

Speech segment details

Note: “Delivery speed” was measured in words per minute (wpm) and “idea density” was measured in propositions per word (ppw).

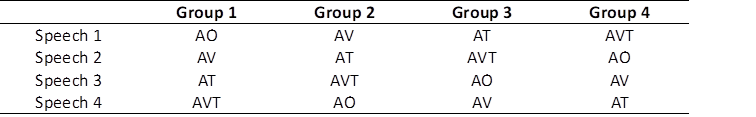

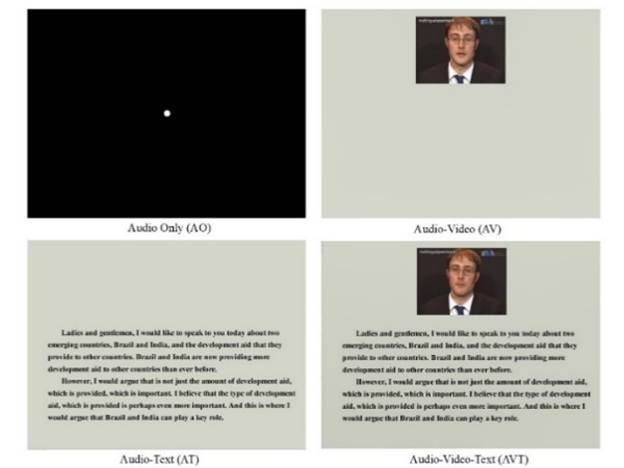

Four experimental conditions (see Table 2 and Figure 1) for each of the speeches were created by using Jiangying and Adobe Photoshop: speech with audio input (AO) only; speech with audio and video of the speaker (AV); speech with audio and written text (AT); and speech with audio, video of the speaker, and written text (AVT). In the AO condition, the participants heard the speech of the video only while they saw a white dot on the screen (Drijvers & Holler, 2023). In the AV and AVT conditions, the video of the speaker was shown in the top third of the screen; the verbatim transcript was displayed in the lower two-thirds of the screen (Seeber et al., 2020). The verbatim text varied with the speaker’s speech stream. The verbatim transcript, designed partially to mimic the presentation format of InterpretBank Model 1, preserves the informational context so as to mitigate semantic ambiguity (Defrancq & Fantinuoli, 2021). Although Model 1 may provide excessive visual information for interpreters, empirical evidence from the CASI interface usability study indicates a practitioner preference for information-rich interfaces (Saeed et al., 2023).

Table 2

Experiment design

3.3 Apparatus

3.3 Apparatus

The experiment was programmed in SR Experiment Builder (SR Research). The participants’ eye-movement data were collected by the EyeLink 1000 Plus eye-tracker and the eye-tracking data gathered were analysed using Data Viewer. The sampling rate adopted in this study was 1000 Hz. The stimuli were presented on a 19-inch LCD monitor with the screen resolution set at 1080*768 pixels; the stimulus covered the entire screen.

Figure 1

Study design

3.4 Experiment procedure

This is a within-subject study in which each participant performs all four SI tasks from English (L2) to Chinese (L1) in different conditions: AO, AV, AT, and AVT. The participants were randomly assigned to one of the four groups, each group performing four SI tasks in four conditions (see Table 2). The order of the four speeches was balanced across the 30 participants in a Latin square design.

The participants were individually tested in a soundproof room owing to the need to record the eye movements of one participant at a time. Prior to an introduction to the study, each participant filled out a pre-task questionnaire about their demographic information and their educational background. Before the actual data-recording began, the participants were given a prepared bilingual glossary containing the vocabulary of the four speeches as preparation within 10 minutes. After that, they carried out a five-minute warm-up task. At the start of the experiment, a nine-point calibration was conducted, the participants sitting 600–650 mm from the eye-tracker. Subsequently, a 4,000 ms visual instruction was provided about the context of each speech that was to be interpreted. The participants performed four interpreting tasks each.

Recalibration was performed on each participant prior to the commencement of each interpreting task. Immediately after the completion of each interpreting task, the participants were asked to rate the cognitive load of the task on a NASA task load questionnaire that is able to reflect their mental demand, effort, level of frustration, and performance (cf. Sun & Shreve, 2014). Finally, an oral interview (in Chinese) was conducted after they had completed all of the interpreting tasks. The total session lasted about 45 minutes.

3.5 Data analysis

This study adopted a mixed-methods approach to obtain qualitative and quantitative data that would form the basis for in-depth analysis. Whereas 30 participants took part in the experiment, one of them had to be excluded from all the measures because of their familiarity with one of the experimental materials.

3.5.1 Overall interpreting quality

To answer research question 1, the overall interpreting quality of CASI in different input conditions was assessed using the rubric-based scale developed by Han (2015). The rating scale is divided into three 8-point subscales that correspond to information completeness, fluency of delivery, and target language quality. Four MTI graduates participated in a half-day training session and then performed the assessment following the procedures specified in Han (2015). Recordings of the target speeches were transcribed. The source-language texts, target-speech recordings, and corresponding transcripts were provided to human raters for analytical rating. Each of the four raters rated each of the 116 interpreted speeches (29 participants × 4 conditions). The average measure intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were calculated in each condition of interpretation; all of the inter-rater reliability scores were above 0.7, indicating a high degree of reliability. The ratings from the four raters were averaged for subsequent analyses.

3.5.2 NASA Task Load Index (TLX) questionnaire

To answer research question 2, cognitive load was measured using the NASA-TLX scale. To measure the subjective overall cognitive load, subjective psychometric rating scales were used. This instrument was selected because it has been proved to be valid, non-intrusive, and easy to implement (Rubio et al., 2004). The NASA Task Load Index (NASA-TLX), developed by Hart and Staveland (1988) and adapted by Sun and Shreve (2014), was used. It consists of four subscales that measure different dimensions of workload: mental demand, effort, frustration, and performance. The aggregate TLX score and the scores for all four subscales were reported in response to recent calls (Bolton et al., 2023; Galy et al., 2018). In total, 29 participants returned valid questionnaires.

3.5.3 Eye-movement data

To answer research question 3, we measured the interpreters’ attention distribution across different input conditions and explored their attention division and coordination in the AVT condition. For this purpose, eye-tracking data were analysed; these included the average fixation duration (AFD) and the dwell-time percentage (DT%). The quality of the eye-tracking data for analysis was assessed using the gaze time on screen. Recordings with a valid gaze sample of more than 80% were used for further analysis in the present study (Hvelplund, 2014). We also discarded those data whose recording was affected by technical problems. This yielded valid eye-movement data from 24 participants for dwell-time percentage analysis in the AVT conditions and for AFD analysis in the AV, AT, and AVT conditions. One area of interest (AOI) was drawn in the AV condition (the speaker) and the AT condition, respectively. The AOIs of the video area in the AV condition and the text area in the AT condition were marked as “AV_V” and “AT_T”. Two AOIs were drawn in the AVT condition: one for the speaker’s video and one for the verbatim text. The AOIs of the video area in the AVT condition were marked as “AVT_V” and the text area as “AVT_T”. Interest periods were established for the material of each video. The AFD was used to examine the distribution patterns and duration across different AOIs with the aim of revealing differences in attentional allocation and adaptations in cognitive processing strategies among the interpreters under various input conditions. The dwell-time percentage was used as a measure of visual attention to examine the interpreters’ attention division and coordination in AVT-based CASI.

3.5.4 Interview data

In addition to analysing the AFD and the dwell-time percentage in the eye-tracking data, we collected interview data as a supplement to analyse the way the participants divided and coordinated their attention across various input modalities in the AVT condition. For this purpose, a semi-structured interview was conducted with each participant. The interview questions centred on “How did the audio, video, and text affect the allocation and coordination of your attention in the AVT condition?” The interviews were recorded and then transcribed into text for analysis.

3.5.5 Statistical analyses

To derive the qualitative data, statistical analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 26. Normality was checked for all the data using the Shapiro-Wilk test. We conducted repeated measures ANOVA for normally distributed data and the Friedman test for non-normally distributed data. A significance level of 0.05 was adopted for all the statistical analyses. The quantitative data obtained from the interviews were analysed using NVivo 11.

4. Results

4.1 Overall interpreting quality

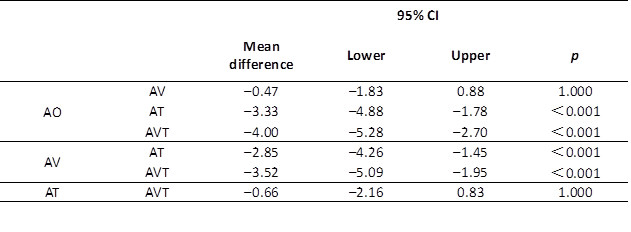

A one-way repeated ANOVA found that the four input conditions differed significantly in the interpreting quality scores (F (3, 84) = 30.853, p < .001, partial η² = .524). Post-hoc analysis with a Bonferroni adjustment showed that the interpreting quality in the AO condition (M = 13.50, SD = 3.03) was significantly lower than that in the AT condition (M = 16.83, SD = 3.50, p < .001) and the AVT condition (M = 17.49, SD = 2.64, p < .001). Furthermore, the AV condition (M = 13.97, SD = 2.86) led to significantly lower scores than the AT (p < .001) and the AVT conditions (p < .001). No significant differences were found between the AO and the AV conditions (p = 1.00). Although the difference between the AT and the AVT conditions did not reach statistical significance (p = 1.00), the interpreting quality was numerically higher in the AVT condition compared to the AT condition; this suggests a possible trend favouring AVT. The test statistics are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3

Comparison of the interpreting quality under different input conditions

4.2 NASA-TLX questionnaire

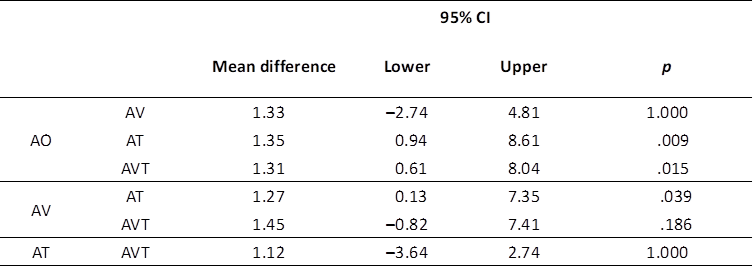

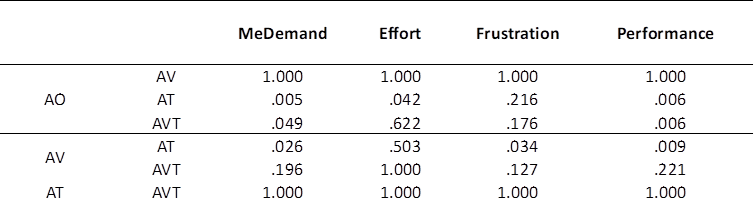

NASA-TLX was used to assess the cognitive load under different input conditions. The aggregate TLX and all subscales have been compared (Table 4 and Table 5). A one-way repeated measures ANOVA showed that the aggregate TLX score differed statistically significantly between the four input conditions (F (3, 84) = 6.579, p < .0001, partial η2 = 0.19). Post-hoc analysis with a Bonferroni adjustment revealed that the aggregate TLX in the AO condition was significantly higher than that in the AT condition (p = .009) and the AVT condition (p = .015); the score in the AV condition was significantly higher than that in the AT condition (p = .039).

Table 4

Means (SD) of aggregate and subscale score of TLX under different conditions

Table 5

Table 5

Comparison of subjective rating of aggregate TLX under different input conditions

A closer inspection of the subscales of cognitive load found that differences exist in every subscale (Table 6). This means that the participants experienced the lowest mental load and felt the most successful in the AT condition. They devoted the most effort in the AO condition and experienced the most frustration in the AV condition.

Table 6

|

Comparison of p-values of TLX subscales under different input conditions

4.3 Attention distribution across input conditions and in AVT-based CASI

4.3.1 Allocation of visual attention across visual input conditions and in AVT-based CASI

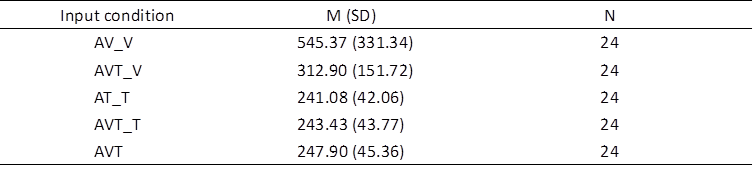

To examine how the interpreters allocated their visual attention across the visual input conditions, we analysed the AFD in the areas of interest of the AV (video), AT (text), and AVT (video and text) conditions (Table 7). The results show that the input condition did induce significant differences in the AFD (F (1.339, 1220571.688) = 16.156, p < .0001, partial η2 = 0.413). Post-hoc analysis with a Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons indicated that there was a significant difference between the AV_V and AT_T conditions (p = .002), the AV_V and AVT_V conditions (p = .024), the AV_V and AVT_T conditions (p = .002), and the AV_V and AVT conditions (p = .002). Compared to the AT condition, cognitive load increased in the AVT condition, but the difference did not reach a significant level. The significant differences of AV_V from AT_T and AVT_T are predictable, as “fixations durations in scene perception tend to have a longer average duration than in reading, and the range of fixation durations is greater” (Nuthmann & Anderson, 2012). The significant difference in AFD between AV_V and AVT suggests that the inclusion of textual information allowed the participants to achieve comprehension in a shorter overall fixation duration, indicating improved task efficiency. Furthermore, the absence of a significant difference in AFD between AT_T and AVT_T implies that the cognitive resources required for text processing remain relatively stable. In contrast, the significantly higher AFD observed in AV_V compared to AVT_V corroborates the view that the presence of text altered the interpreters’ attention-allocation patterns, diverting more cognitive resources towards textual information rather than visual content.

Descriptive statistics on AFD (ms) in the AV, AT, and AVT conditions

Note: AV_V

= video in the AV condition; AT_T = text in the AT condition; AVT_V = video in

the AVT condition; AVT_T = text in the AVT condition; AVT = a mean of

average fixation duration based on all the fixations in both AOIs of this

condition.

Note: AV_V

= video in the AV condition; AT_T = text in the AT condition; AVT_V = video in

the AVT condition; AVT_T = text in the AVT condition; AVT = a mean of

average fixation duration based on all the fixations in both AOIs of this

condition.

To examine more closely the way the interpreters devoted their attention to different information sources in AVT-based CASI, we analysed eye-movement data under the AVT condition; in particular, we focused on the dwell-time percentage in two distinct areas: video (dynamic visual input) and text. Paired-sample t-test results showed that the interpreters paid significantly more visual attention to the text (M = 0.04%, SD = 0.07%) than to the video (M = 0.93%, SD = 0.07%, t(27) = -26.56, p < .0001).

4.3.2 Attention division and strategic coordination patterns in AVT-based CASI

Interview data were also analysed to assess the impact of the multimodal input on the participants’ attention division and coordination in the AVT condition. Regarding attention division, 27 of the 29 participants reported concentrating their primary cognitive resources on textual input, with four participants explicitly describing an attention hierarchy of text > audio > video. This information matched the objective eye-tracking data. This allocation strategy was rationalized by several factors. For example, most of the participants reported that “text alleviated listening comprehension load and provided direct lexical support for accuracy when there was difficulty in listening”. According to two participants, “the cognitive burden imposed by text processing was already demanding, leaving no room for other inputs.” Another two stated that “there were no paralinguistic cues in the video that could help comprehension”. Consequently, audio primarily served as an auxiliary cue for text location and monitoring, while the speaker’s video was referenced only under circumstances such as when the speaker paused, the interpreter had spare mental capacity, or the interpreter experienced difficulty keeping up with the speaker’s pace.

Regarding attention coordination, different patterns of strategic coordination were observed. Apart from the benefits brought by text, 10 of the 27 participants reported difficulties in coordinating the simultaneous processing of auditory and visual modalities. As the participants said: “If I tried to watch, I missed the audio; if I focused on listening, I lost track of the text. It’s challenging to manage both concurrently.” In contrast, the remaining 17 participants could actively filter modal information without struggling with multimodal choices. Interestingly, two participants adopted a strategy of prioritizing the auditory input even in multimodal contexts.

5. Discussion

5.1 Impact of input condition on cognitive load and quality

The data collected from the self-reported cognitive load and quality assessment indicate that, compared to the AO and the AV conditions, the AT and the AVT conditions had much lower scores for aggregate TLX, mental strain, effort, frustration, and higher overall interpreting quality. This result is consistent with previous research (Defrancq & Fantinuoli, 2021; Desmet et al., 2018; Li & Chmiel, 2024; Pisani & Fantinuoli, 2021; Prandi, 2015, 2018) in finding that textual support from CASI tools did not impair but rather improved the interpreting quality while concurrently reducing the cognitive load (Chen & Kruger, 2024; Cheung & Li, 2022; Li & Chmiel, 2024; Prandi, 2023). This can be attributed to the textual support provided by the CASI tools, which alleviates interpreters’ memory load (Gile, 2009) through lexical and syntactic referencing. This cognitive offloading allows interpreters to devote more cognitive resources to comprehension and production processes, resulting in an enhanced interpreting quality. In contrast, the participants in the AO and AV conditions were required to comprehend and interpret speech without CASI assistance, relying solely on transient auditory input. According to Leahy and Sweller (2011), such ephemeral auditory signals impose a heavier burden on working memory compared to persistent written text, which renders the task more cognitively demanding. However, since the participants in this study are students, whether professional interpreters benefit to the same extent is still to be determined.

In addition, it is intriguing to find that, although the participants felt the most successful under the AT condition and also experienced the least cognitive strain under it, they attained the highest overall interpreting quality scores under the AVT condition (this despite no statistically significant difference being found between these conditions). This reveals the complex dynamics of the speaker’s visibility in multimodal processing in SI: while potentially inducing a slightly increased cognitive load, it contributed positively to the overall interpreting quality by promoting engagement and providing paralinguistic cues (Peng et al., 2024). This finding backs up the views expressed by both practitioners and scholars (Bühler, 1985; Pöchhacker, 2005) on the critical function that visual access to the speaker plays in SI.

5.2 Strategic shift in attentional allocation across conditions: implications for AVT-based CASI

An analysis of the AFD data reveal a high degree of behavioural adaptability in the interpreters’ attentional allocation patterns across conditions: attention was focused on the video in the AV condition and on the text in the AT condition, whereas a strategic reallocation towards a text-primary, video-secondary pattern was observed in the AVT condition. This adaptive shift can be attributed to a fundamental difference in cognitive processing mechanisms between verbal and non-verbal input. Verbal text primarily facilitates language comprehension by enabling lexical access and syntactic integration, whereas non-verbal input mainly serves to construct situational models and resolve referential links (Liao et al., 2022). Since text offers a more direct and efficient channel for core language processing, the cognitive system prioritizes it to optimize limited resources. This “text primary” strategy can be viewed as an adaptive response to reduce the cognitive load (i.e., the load generated by processing continuous and often ambiguous paralinguistic cues from video), in this way freeing up resources for the cognitive load demands of comprehension and reformulation. The benefit of this strategy is also directly evidenced by the enhanced processing efficiency, as indicated by a significantly shorter overall AFD in the AVT condition compared to the AV condition.

A closer inspection of the interpreters’ attention division and coordination in the AVT-based CASI found some interesting points that may shed light on multimodal processing and the complexity of human–technology interaction. The dwell-time percentage data and interviews indicate that the student interpreters prioritized their attention on written text over auditory speech and the speaker’s visual image. This aligns with the finding of Li and Chmiel (2024) and confirms the Colavita visual dominance effect observed by Chmiel et al. (2020) in SI with text.

Despite the substantial benefits of CASI tools, caution remains warranted in their application for two primary reasons. First, real-world CASI systems may exhibit recognition inaccuracies, given that current ASR technologies are imperfect under certain conditions (O’Shaughnessy, 2024). Inaccuracies in the ASR results provided to interpreters could lead to inaccurate interpreting, as interpreters may fail to notice such errors under a high cognitive workload (Li & Chmiel, 2024). Crucially, the ASR-generated transcripts in this study were perfectly aligned with the source speech. This artificial consistency probably attenuated the interpreters’ vigilance in monitoring audio-textual congruence, which also explains why some of the participants reported devoting predominant attention to the text rather than the audio channel. Whether other CASI configurations, such as target-text presentation or search functions, generate similar effects on cognitive load, interpreting quality, and attentional dynamics deserves further investigation. Second, over-reliance on textual input goes against the recommendation of giving “priority in attention to listening over reading” (Setton & Dawrant, 2016b, p. 281) and the rule that “authoritative input still arrives through the acoustic channel” (Pöchhacker, 2004, p. 19). Since the participants in this study are student interpreters, it is crucial to determine whether the trends seen here hold true for professional interpreters.

The interview data identified different patterns in attention coordination, which could be different strategies that the participants adopted. However, whether different strategic patterns lead to differences in the quality of interpretation is subject to further research. Furthermore, some interpreters reported difficulties in attention coordination in CASI, which is in accordance with the observation made by Defrancq and Fantinuoli (2021) and Frittella (2023). This suggests that CASI is a complex cognitive task. Its complexity is reflected not only in multitasking but also in multimodal processing (Seeber, 2017). On the one hand, the participants must balance the allocation of cognitive resources across listening, reading, memorization, comprehension, production, and self-monitoring. On the other, they must decide in real-time which sources of information – auditory, visual, or textual – to select, extract, and integrate, while dynamically constructing cross-modal meaning. With limited working memory (Miller, 1956) and cognitive resources (Kahneman, 1973) the temporal overlap of multitasking causes mutual interference, resulting in coordination difficulties.

5.3 Implications

This study yields substantial theoretical, practical, and pedagogical implications. Theoretically, its findings provide robust evidence in support of the inherent complexity of CASI in multitasking and multimodal processing. This aligns with the perspective advocated by Seeber (2017) and Wang (2023) that SI is essentially a multimodal interaction. Furthermore, it responds to Mellinger’s (2019, 2023) and Fantinuoli’s (2018a, 2018b) call to systematically investigate the ways in which CAI tools engage with – enabling, mediating, constraining, and reshaping – interpreting processes.

Practically speaking, our findings regarding improved interpreting quality and reduced cognitive load when verbatim written text and the visibility of the speaker were available corroborate the results of previous research investigating the feasibility of technology in the interpreting workflow (Defrancq & Fantinuoli, 2021; Desmet et al., 2018). These findings not only provide empirical backing to inform the design and development of CASI tools, but also offer promising avenues for applying CASI tools so as to facilitate interpreting. The preference for text over audio found in the present study suggests that training interpreters to manage attention skilfully and actively when using CASI tools should be an important component of CAI training. From another perspective, it is advisable for software developers to bear in mind the existence of the Colavita visual dominance effect and to ground their user-interface design in empirical evidence of the impact on interpreters of different proportions of information, interface options, and display configurations.

This study holds significant pedagogical relevance for interpreter training too. First, the difficulty experienced with coordination indicates that educators should consider an iterative design approach when selecting suitable activities and instructional materials, and carefully scaffold instruction as needed. Secondly, the study found that the input conditions significantly affect the interpreting quality and the cognitive load. It therefore offers empirical support for diversifying the input conditions during interpreting training, aptitude testing, and professional assessments. Whereas audio input has traditionally dominated these domains – for instance, the current interpreter training, accreditation, and aptitude tests, particularly in China, heavily rely on audio speeches (Shang & Xie, 2024) – other input conditions remain understudied. Crucially, it must be borne in mind that different input conditions entail different cognitive mechanisms and coping strategies. This means that greater emphasis should be placed on a diverse range of input conditions in training programmes and also in interpreter accreditation and aptitude tests. By doing so, interpreting education will not only reflect the real-world situations that interpreters may encounter in practice, but will also equip student interpreters with diverse skill sets. In this way, interpreting education will prepare student interpreters more constructively to function effectively across a wide range of services.

6. Conclusion

This study investigated the impact of multimodal input in CASI on the overall interpreting quality, cognitive load, and interpreters’ attention dynamics of a group of student interpreters. The findings suggest that the visual input provided by CASI tools significantly improved the interpreting quality and reduced the cognitive load of this cohort. Specifically, the audio–video–text input condition resulted in the highest overall interpreting quality and relatively low cognitive load, a result that suggests promising prospects for computer-assisted human interpreting. Moreover, attention was focused on the video in the AV condition and on the text in the AT condition, while a strategic realignment towards a text-primary, video-secondary pattern was observed under the AVT condition. The student interpreters presented different patterns of attention division and coordination in the AVT-based CASI. Given the complexity of the human–technology interaction identified in this study, coupled with the growing popularity of CASI tools in facilitating SI, we call for the collection of more empirical data on the cognitive impact of CASI adoption before offering specific suggestions for CASI design.

Several limitations must be borne in mind before we are able to generalize the findings in this study. First, since the experiment was conducted with student interpreters, the results may not be readily applicable to professional interpreters. Secondly, we acknowledge the discrepancies between our experimental setting and the real CASI tools, which may affect the generalizability of our research findings. For instance, ASR may not achieve perfect recognition owing to certain latencies. Consequently, our findings represent the potential maximum efficiency that could be attained with such a perfect system. Moreover, the possible cognitive impact of alternative CASI configurations, such as target-text presentation and term searching for interpreting, requires further empirical exploration. Future studies should consider adopting the real CASI software equipped with diverse configuration options that is currently available on the market.

To conclude, the empirical findings in this study underscore the impact of multimodal input on the overall interpreting quality and cognitive load and also highlight the complexity of the multimodal processing that characterises CASI. We therefore call for more research that delves into the cognitive mechanisms of multimodal processing in order to inform CASI tool development, interpreting practice, and interpreting education in an age of rapid technological development.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the editors, the anonymous reviewers, and Dr Yanfang Jia for their valuable comments and feedback on the earlier drafts of this article. Many thanks must also go to the raters and the participants for the time and effort they put into their tasks.

Funding

This work was supported by the Key project of Hunan Province for the reform of graduate education (grant number 2022JGZD021).

References

Bolton, M. L., Biltekoff, E., & Humphrey, L. (2023). The mathematical meaninglessness of the NASA Task Load Index: A level of measurement analysis. IEEE Transactions on Human Machine Systems, 53(3), 590–599. https://doi.org/10.1109/THMS.2023.3263482

Brown, C., Snodgrass, T., Kemper, S. J., Herman, R., & Covington, M. A. (2008). Automatic measurement of propositional idea density from part-of-speech tagging. Behavior Research Methods, 40(2), 540–545. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.2.540

Bühler, H. (1985). Conference interpreting: A multichannel communication phenomenon. Meta: Journal des traducteurs, 30(1), 49–54. https://doi.org/10.7202/002176ar

Chen, S., & Kruger, J. L. (2023). The effectiveness of computer-assisted interpreting: A preliminary study based on English–Chinese consecutive interpreting. Translation & Interpreting Studies, 18(3), 399–420. https://doi.org/10.1075/tis.21036.che

Chen, S., & Kruger, J. L. (2024). A computer-assisted consecutive interpreting workflow: Training and evaluation. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 18(3), 380–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2024.2373553

Cheung, A. K., & Li, T. (2022). Machine aided interpreting: An experiment of automatic speech recognition in simultaneous interpreting. Translation Quarterly, 104(2), 1–20.

Chmiel, A., Janikowski, P., & Lijewska, A. (2020). Multimodal processing in simultaneous interpreting with text: Interpreters focus more on the visual than the auditory modality. Target. International Journal of Translation Studies, 32(1), 37–58. https://doi.org/10.1075/target. 18157.chm

Defrancq, B., & Fantinuoli, C. (2021). Automatic speech recognition in the booth: Assessment of system performance, interpreters’ performances and interactions in the context of numbers. Target. International Journal of Translation Studies, 33(1), 73–102. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.19166.def

Desmet, B., Vandierendonck, M., & Defrancq, B. (2018). Simultaneous interpretation of numbers and the impact of technological support. In C. Fantinuoli (Ed.), Interpreting and technology (pp. 13–27). Language Science Press. https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.1493291

Drijvers, L., & Holler, J. (2023). The multimodal facilitation effect in human communication. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 30(2), 792–801. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-022-02178-x

European Commission. (2012a, January 19). Brazil and India: A different type of development aid. Speech Repository. Retrieved October 31, 2022, from https://speech-repository.webcloud.ec.europa.eu/speech/brazil-and-india-different-type-development-aid

European Commission. (2012b, June 19). Recruitment of South African nurses to work in the British National Health Service. Speech Repository. Retrieved October 31, 2022, from https://speechrepository.webcloud.ec.europa.eu/speech/recruitment-south-african-nurses-work-britishnational-health-service

European Commission. (2017, June 22). Handheld devices and developmental delays in small children. Speech Repository. Retrieved October 31, 2022, from https://speech-repository.webcloud. ec.europa.eu/speech/handheld-devices-and-developmental-delays-small-children

European Commission. (2019, March 29). Military spending: Looking for the balance between strength and diplomacy? Speech Repository. Retrieved October 31, 2022, from https://speechrepository.webcloud.ec.europa.eu/speech/military-spending-looking-balance-betweenstrength-and-diplomacy

Fantinuoli, C. (2018a). Computer-assisted interpreting: Challenges and future perspectives. In I. Durán-Muñoz & G. Corpas Pastor (Eds.), Trends in e-tools and resources for translators and interpreters (pp. 153–174). Koninklijke Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004351790_009

Fantinuoli, C. (2018b). Interpreting and technology: The upcoming technological turn. In C. Fantinuoli (Ed.), Interpreting and technology (pp. 1–12). Language Science Press. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1493289

Fantinuoli, C. (2023). Towards AI-enhanced computer-assisted interpreting. In G. Corpas Pastor & B. Defrancq (Eds.), Interpreting technologies: Current and future trends (pp. 46–71). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/ivitra.37

Frittella, F. M. (2022). CAI-tool supported SI of numbers: A theoretical and methodological contribution. International Journal of Interpreter Education, 14(1), 32–56. https://doi.org/10.34068/ijie.14.01.05

Frittella, F. M. (2023). Usability research for interpreter-centred technology: The case study of SmarTerp. Language Science Press. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7376351

Galy, E., Paxion, J., & Berthelon, C. (2018). Measuring mental workload with the NASA-TLX needs to examine each dimension rather than relying on the global score: An example with driving. Ergonomics, 61(4), 517–527. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139.2017.1369583

Gile, D. (2009). Basic concepts and models for interpreter and translator training (rev. ed.). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.8

Han, C. (2015). Investigating rater severity/leniency in interpreter performance testing: A multifaceted Rasch measurement approach. Interpreting, 17(2), 255–283. https://doi.org/ 10.1075/intp.17.2.05han

Hart, S. G., & Staveland, L. E. (1988). Development of NASA-TLX (Task Load Index): Results of empirical and theoretical research. In P. A. Hancock & N. Meshkati (Eds.), Human mental workload (pp. 139–183). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-4115(08)62386-9

Hvelplund, K. T. (2014). Eye tracking and the translation process: Reflections on the analysis and interpretation of eye-tracking data. Monografías de Traducción e Interpretación, Special issue, 201–223. https://doi.org/10.6035/MonTI.2014.ne1.6

Kahneman, D. (1973). Attention and effort. Prentice Hall. https://doi. org/10.2307/1421603

Kalyuga, S., & Sweller, J. (2014). The redundancy principle in multimedia learning. In R. E. Mayer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (2nd ed., pp. 247–262). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139547369.013

Leahy, W., & Sweller, J. (2011). Cognitive load theory, modality of presentation and the transient information effect. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 25(6), 943–951. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1787

Lederer, M. (1981). La Traduction Simultanée : Expérience et Théorie. Minard.

Li, T., & Chmiel, A. (2024). Automatic subtitles increase accuracy and decrease cognitive load in simultaneous interpreting. Interpreting, 26(2), 253-281. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.00111.li

Liao, S., Yu, L., Kruger, J. L., & Reichle, E. D. (2022). The impact of audio on the reading of intralingual versus interlingual subtitles: Evidence from eye movements. Applied psycholinguistics, 43 (1), 237–269. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716421000527

Mackintosh, J. (2003). The AIIC workload study. Forum, 1(2), 189–214. https://doi.org/10.1075/forum.1.2.09mac

Mellinger, C. D. (2019). Computer-assisted interpreting technologies and interpreter cognition: A product and process-oriented perspective. Tradumàtica, 17, 33–44. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/tradumatica.228

Mellinger, C. D. (2023). Embedding, extending, and distributing interpreter cognition with technology. In G. Corpas Pastor & B. Defrancq (Eds.), Interpreting technologies: Current and future trends (pp. 195–216). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/ivitra.37.08mel

Miller, G. (1956). Human memory and the storage of information. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, 2(3), 129–137. https://doi. org/10.1109/TIT.1956.1056815

Nuthmann, A., & Henderson, J. M. (2012). Using CRISP to model global characteristics of fixation durations in scene viewing and reading with a common mechanism. Visual Cognition, 20(4–5), 457–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/13506285.2012.670142

O'Shaughnessy, D. (2024). Trends and developments in automatic speech recognition research. Computer Speech & Language, 83(101538), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csl.2023.101538

Paas, F. G. (1992). Training strategies for attaining transfer of problem-solving skill in statistics: A cognitive-load approach. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(4), 429–434. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.84.4.429

Peng, X., Wang, X., & Chen, G. (2024). Text availability and the speaker’s visibility in simultaneous interpreting: effects on the process, product, and interpreters’ perceptions. Perspectives, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2024.2414477

Pisani, E., & Fantinuoli, C. (2021). Measuring the impact of automatic speech recognition on number rendition in simultaneous interpreting. In B. Zheng & C. Wang (Eds.) Empirical studies of translation and interpreting (pp. 181–197). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003017400-14

Pöchhacker, F. (2004). Introducing interpreting studies. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203504802

Pöchhacker, F. (2005). From operation to action: Process-orientation in interpreting studies. Meta Journal des Traducteurs, 50(2), 682–695. https://doi.org/10.7202/011011ar

Prandi, B. (2015). The use of CAI tools in interpreters’ training: A pilot study. In Proceedings of the 37th Conference Translating and the Computer (pp. 48–57). AsLing.

Prandi, B. (2018). An exploratory study on CAI tools in simultaneous interpreting: Theoretical framework and stimulus validation. In C. Fantinuoli (Ed.), Interpreting and technology (pp. 29–59). Language Science Press. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1493293

Prandi, B. (2023). Computer-assisted simultaneous interpreting: A cognitive-experimental study on terminology. Language Science Press. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7143056

Rennert, S. (2008). Visual input in simultaneous interpreting. Meta. Journal des Traducteurs, 53(1), 204–217. https://doi.org/10.7202/017983ar

Rubio, S., Díaz, E., Martín, J., & Puente, J. M. (2004). Evaluation of subjective mental workload: A comparison of SWAT, NASA-TLX, and workload profile methods. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 53(1), 61–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2004.00161.x

Saeed, M. A., Rodríguez González, E., Korybski, T., Davitti, E., & Braun, S. (2023). Comparing interface designs to improve RSI platforms: Insights from an experimental study. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Human-informed Translation and Interpreting Technology (HiT-IT 2023) (pp. 147–156). https://doi.org/10.26615/issn.2683-0078.2023_013

Seeber, K. G. (2011). Cognitive load in simultaneous interpreting: Existing theories — new models. Interpreting, 13(2), 176–204. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.13.2.02see

Seeber, K. G. (2017). Multimodal processing in simultaneous interpreting. In J. W. Schwieter & L. Wei (Eds.), The handbook of translation and cognition (pp. 461–475). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119241485.ch25

Seeber, K. G., Keller, L., & Hervais-Adelman, A. (2020). When the ear leads the eye: The use of text during simultaneous interpretation. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 35(10), 1480–1494. https://doi.org/10.1080/23273798.2020.1799045

Setton, R. (1999). Simultaneous interpretation: A cognitive–pragmatic analysis. John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.28

Setton, R., & Dawrant, A. (2016a). Conference interpreting: A trainer's guide. John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.121

Setton, R., & Dawrant, A. (2016b). Conference interpreting: A complete course. John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.120

Shang, X., & Xie, G. (2024). Investigating the impact of visual access on trainee interpreters’ simultaneous interpreting performance. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 18(4), 645–663. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2024.2381404

Sun, S., & Shreve, G. M. (2014). Measuring translation difficulty: An empirical study. Target. International Journal of Translation Studies, 26(1), 98–127. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.26.1.04sun

Wang, B. (2023). Exploring information processing as a new research orientation beyond cognitive operations and their management in interpreting studies: Taking stock and looking forward. Perspectives, 31(6), 996–1013. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2023.2200955