Syntactic complexity as a discriminator between machine and human interpreting: A machine-learning classification approach

Yao Yao

Xi’an Jiaotong University

The Hong Kong Polytechnic University

https://orcid.org/0009-0003-7005-9075

Kanglong Liu

The Hong Kong Polytechnic University

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3962-2563

Andrew Kay-Fan Cheung

The Hong Kong Polytechnic University

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0848-1980

Dechao Li

The Hong Kong Polytechnic University

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6312-6581

Abstract

The emergence of language technologies has positioned machine interpreting (MI) as a scalable solution to real-time multilingual communication, necessitating systematic examinations of its linguistic characteristics compared to those of human interpreting (HI) in order to foster more human-like outputs. Whereas initial studies have investigated various linguistic dimensions, syntactic complexity – a key indicator of linguistic sophistication and processing – remains under-explored in MI–HI comparisons. This study sought to bridge this gap by leveraging machine-learning classifiers to differentiate MI and HI based on multidimensional syntactic complexity metrics. We compiled a comparable Chinese-to-English corpus from government press conferences featuring HI renditions by professional interpreters and MI outputs generated by the iFlytek platform from identical source speeches. Ten machine-learning algorithms were trained on selected metrics across five dimensions, with ensemble models developed from top-performing classifiers and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) applied to quantify the importance of features. The results show that the equal-weighted ensemble of SVM, GB, and MLP yielded optimal discriminative performance (AUC = 84.29%, Accuracy = 76.15%). SHAP analysis revealed a distinct hierarchy of feature salience. Specifically, MI outputs exhibited “additive complexity”, which reflects sequential, modular processing within cascading architectures, whereas HI demonstrated “integrative complexity” derived from conceptually mediated processing that balances cognitive constraints against communicative goals. These findings advance our theoretical understanding of computational versus human language-processing mechanisms and provide empirical foundations for developing more naturalistic MI systems, thereby contributing to the emerging field exploring the interplay between interpreting and technology.

Keywords: human interpreting, machine interpreting, machine-learning classification, syntactic complexity, ensemble model, SHapley Additive exPlanations

1. Introduction

In contrast to the technologies designed to augment human interpreters, MI, also termed automatic speech translation (AST), embodies a paradigm that is aimed at “replacing human interpreters” (Fantinuoli, 2018, p. 5). This automation typically follows one of two architectures: (1) the end-to-end model, which translates speeches directly without intermediary steps; and (2) the more prevalent cascading model, which links automatic speech recognition (ASR), machine translation (MT), and occasionally voice synthesis or text-to-speech synthesis (TSS) (Fantinuoli, 2018, 2025). Despite significant advancements, MI has yet to achieve parity with human interpreting (HI), owing to persistent constraints such as algorithmic bias, limited contextual sensitivity, and inadequate handling of pragmatic nuances (Chen & Kruger, 2024; Liu & Liang, 2024; Pöchhacker, 2024). Yet, market trends indicate that, driven by economic concerns, raw MI outputs are increasingly being deployed as final products (Downie, 2023). This trend reveals a troubling mismatch: whereas MI adoption accelerates in practical settings, it has received disproportionately limited scholarly attention, which has fostered widespread automation anxiety among interpreters amid a dearth of empirical insights (Vieira, 2018). This confluence of factors underscores the urgent need for empirical investigations to delineate the capabilities and limitations of MI, particularly as its use proliferates in diverse communicative settings without adequate understanding of its linguistic traits and constraints.

Notwithstanding the growing body of research on MI, including conceptualizations (Pöchhacker, 2024), quality assessment (Fantinuoli & Prandi, 2021; Lu, 2022, 2023), sentiment analysis (Zhang et al., 2025), and the analysis of machine translationese, defined as the distinct linguistic features of machine-generated translations (Bizzoni et al., 2020), significant gaps persist in the literature. First, the linguistic divergences between MI and HI outputs warrant more nuanced analysis to elucidate how machine-generated discourse deviates from the “gold standard” of professional interpreter renditions (Fantinuoli & Prandi, 2021, p. 3). In particular, inconsistent findings regarding syntactic complexity across investigations (e.g., Bizzoni et al., 2020; Liu & Liang, 2024; Zhang et al., 2025) call for more granular analytical lenses to be applied. Second, previous analyses have predominantly relied on traditional inferential statistics, which struggle to capture complex, non-linear interactions among linguistic features or to pinpoint the features that are driving distinctions. Machine-learning algorithms, with their capabilities in pattern recognition and the ranking of the importance of features, hold promise for modelling these intricate dynamics and facilitating robust comparisons between mediated and non-mediated language (e.g., Baroni & Bernardini, 2006; Hu & Kübler, 2021; Liu et al., 2022; Popović et al., 2023). Nevertheless, their application in distinguishing interpreting modalities remains underexplored – a research lacuna that this study aims to address.

Motivated by these considerations, the present study aimed to identify syntactic complexity features that differentiate MI from HI by employing machine-learning classifiers. Extending beyond commonly used classifiers, such as support vector machines (SVMs), we evaluated a broader array of models and established ensemble models by combining top-performing classifiers to boost classification performance. To enhance the interpretability of the models, we applied SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) values (Lundberg & Lee, 2017) to quantify the predictive impact of each feature; in this way we were able to uncover the most salient syntactic features that distinguish MI from HI. The significance of this study lies in its potential to bridge the divide between technological innovation and linguistic structure, providing evidence-based insights that can refine MI systems to produce outputs more closely aligned to HI norms. Moreover, these findings are highly valuable for designing interpreter training curricula and empowering professionals to adapt effectively to hybrid human–machine systems while building professional resilience amid ongoing digital transformation.

2. Related work

2.1 Machine–human differences in interpreted language patterns

Recent developments in language technologies have intensified scholarly attention to the distinct linguistic features that distinguish human- from machine-generated translations and interpreting. Investigations have spanned various dimensions, such as lexical choice, syntactic organization, and discourse coherence (De Clercq et al., 2021; Jiang & Niu, 2022; Krüger, 2020; Luo & Li, 2022; Vanmassenhove et al., 2019). These efforts often draw on the concept of translation universals, including simplification, explicitation, and normalization (Baker, 1993; Laviosa, 1998), which vary depending on whether the agent is human or machine. Given that this body of work has primarily concerned itself with MT, investigations into interpreting modalities are relatively limited, with direct comparisons between MI and HI remaining notably scarce.

A foundational study by Bizzoni et al. (2020) explored translationese patterns in English–German outputs from “in-house MT engines” (p. 282), which were specifically trained for speech and text translation, respectively; they also compared these patterns with those in human translation (HT) and HI. Moreover, they operationalized syntactic complexity using two indicators: (1) part-of-speech (PoS) perplexity for sequential patterns and (2) dependency parsing distances for hierarchical structures. Their results indicate that HI exhibits cognitive-induced syntactic simplification that is characterized by shorter dependency distances and greater variability in PoS sequences, whereas MT fails to replicate these patterns, displaying instead source language (SL) interference that is determined by the mechanisms of the MT systems. Crucially, the differences were attributed to the translation agent (human vs machine) rather than to the register (written vs spoken). Their analysis, however, was confined to only two features and “speech-oriented” MT systems, pointing to the need for more nuanced investigations into syntactic variations between real MI systems and HI.

Extending this line of enquiry, Liu and Liang (2024) conducted a quantitative comparison of outputs by “state-of-the-art MT technologies” (p. 3), including Google Translate and Baidu Translate, against those generated by professional interpreters in Chinese–English settings. Through a multidimensional analysis of linguistic features across descriptive, lexical, syntactic, and cohesive levels, they found that HI typically features simpler vocabulary, shorter sentences, and stronger discourse cohesion, with an emphasis on semantic explicitation and accessibility. These comparative advantages could be attributed to the dual influences of real-time cognitive demands on interpreters and their superior contextual awareness and pragmatic competence. Nevertheless, their focus on text-to-text MT using transcriptions of source speeches neglects the complete MI architecture, which incorporates ASR and TSS technologies, limiting the relevance of findings to authentic interpreting situations. Furthermore, the limited size of the three sub-corpora, with an average of 17,500 tokens, and the 15,000-token limit for analysis set by Coh-Metrix, may possibly weaken the robustness and generalizability of the results. Third, inferential statistical methods, such as one-way ANOVA, may hinder the identification of intricate interactions between linguistic features and their respective contributions to observed differences.

In a more recent study, Zhang et al. (2025) investigated lexico-syntactic complexity in a Chinese–English intermodal corpus derived from government press conferences, which situated MI as an intermediate register between HI and HT. Employing the L2 Syntactic Complexity Analyzer (L2SCA) (Lu, 2010), they observed that MI consistently surpasses HI regarding the length of production units, coordination density, and specific structures; this outcome can be ascribed to the superior algorithmic capabilities that are not hindered by human-processing constraints. However, the reliance on isolated univariate tests overlooked potential correlations among the 14 L2SCA indices, especially those in the same dimension, and excluded machine-learning models for assessing the importance of features or the generalizability of models. Taken together, the present study takes into account these limitations regarding MI–HI comparisons by integrating multivariate collinearity diagnostics, classification algorithms, and SHAP-based feature attribution.

2.2 Syntactic complexity of interpreted language

Syntactic complexity functions as an essential indicator of linguistic competence and underlying cognitive mechanisms, encompassing as it does the diversity and intricacy of grammatical constructions in output (Ortega, 2003). In second language acquisition (SLA) research, it is conceptualized as a multidimensional construct influenced by factors such as task type, proficiency level, and language modality (Biber et al., 2011; Kyle & Crossley, 2018; Lu & Ai, 2015). Lu (2010) systematized the measurement of syntactic complexity by proposing 14 metrics that have been widely adopted in SLA studies. These metrics are grouped into five dimensions: length of production unit, amount of subordination, amount of coordination, degree of phrasal sophistication, and overall sentence complexity. These metrics enable a thorough analysis of both surface-level and underlying structural aspects of syntactic usage, with L2SCA serving as a computational tool with which to automate the assessment process.

In translation studies, this holistic approach has been employed to compare translated and non-translated texts systematically, thereby elucidating distinct patterns in syntactic complexity (e.g., Chen et al., 2024; Liu & Afzaal, 2021; Xu & Li, 2021; Wang et al., 2023). For instance, Chen et al. (2024) adapted this framework to constrained languages, comparing translated English (TE), English as a Foreign Language (EFL), and native English (NE) texts. Their findings indicated that both TE and EFL texts exhibit longer sentences but reduced sentence complexity and subordination compared to NE texts; this suggests a tendency towards strategic syntactic simplification in translated and learner-produced texts. Studies in interpreting, however, have attracted proportionally fewer empirical investigations that employ such analytical frameworks (Li et al., 2025; Liu et al., 2023; Xie et al., 2025). Liu et al. (2023) made noteworthy contributions by employing L2SCA metrics to compare interpreted and non-interpreted languages. They demonstrated that interpreted language generally displays lower syntactic complexity, with a preference for shorter clauses and less subordination so as to sustain fluency and accommodate the demands of real-time processing. This study highlights the ways in which cognitive and linguistic constraints shape syntactic choices in interpreting, providing valuable insights into bilingual speech production.

The scarcity of research comparing the syntactic complexity of MI and HI represents a critical gap in our understanding of interpreted language production, particularly given the rapid advancement and deployment of MI systems in professional contexts. And whereas Zhang et al. (2025) initiated this comparative enquiry, systematic investigation of the syntactic profiles of MI versus HI remains largely unexplored. This lacuna is particularly concerning as machine systems that operate without the cognitive constraints inherent in human processing may generate structurally complex yet contextually inappropriate output. The application of Lu’s (2010) framework to MI–HI comparisons could therefore yield crucial insights that lead to both theoretical understanding and practical applications of MI systems.

2.3 Application of machine-learning classification to translational language

Machine-learning classifiers have revolutionized the detection of linguistic patterns in translation studies, surpassing traditional statistics by modelling non-linear interactions and ranking the importance of features (Sen, 2021; Wang, Liu & Liu, 2024; Wang, Liu & Moratto, 2024). Baroni and Bernardini (2006) pioneered this trend by using SVMs to identify translationese via lexical and syntactic features, in the process highlighting the potential of machine learning to uncover subtle linguistic differences that may not be evident through conventional statistical analysis. Building upon this line of research, Ilisei et al. (2010) applied eight classifiers to test the simplification hypothesis in Spanish translations. Here, the SVMs achieved a significantly improved accuracy level of 81.76%, which underscores the effectiveness of machine-learning classifiers in testing translational universals. Hu and Kübler (2021) implemented SVMs combined with tenfold cross-validation to distinguish translated Chinese variants originating from diverse source languages. Their findings emphasized the importance of tailored feature selection and demonstrated that machine-learning classifiers could effectively adapt to various linguistic and translation contexts. Liu et al. (2022) tested multiple classifiers, including SVMs, linear discriminant analysis (LDA), Random Forests, and Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), based on seven entropy-based metrics. Focusing specifically on distinguishing translated from non-translated Chinese texts, their findings demonstrated that SVMs achieved the highest level of performance, with an AUC of 90.5% and an accuracy level of 84.3%. These outcomes highlight the ability of the SVMs to manage complex linguistic features. As one of the few studies to use L2SCA metrics, that of Wang, Liu and Liu (2024) employed Lu’s (2010) syntactic complexity metrics to distinguish between translated and non-translated corporate annual reports. They used various classifiers and ensemble models, achieving a notable AUC of 99.3%. The study demonstrated the effectiveness of syntactic complexity indicators in machine-learning classification and emphasized the ways in which ensemble models can improve performance by blending the strengths of different algorithms.

Notwithstanding the progress made through these studies, the deployment of machine learning in interpreting research, particularly for differentiating MI from HI, has not been thoroughly examined. Although SVMs have dominated previous studies, it is essential to explore a wider array of potential classifiers in order to identify the best-performing models. Moreover, establishing ensemble models could provide notable benefits since they combine the strengths of various algorithms, potentially exceeding the performance of single models by capturing more diverse patterns and minimizing overfitting (Rokach, 2010; Sagi & Rokach, 2018). Finally, the interpretability of machine-learning models, often considered as “black boxes”, can be enhanced using techniques such as SHAP values (Liu et al., 2023; Lundberg & Lee, 2017). These values explicitly quantify the contribution of each feature to the model’s predictions, in this way clarifying those features that influence classification decisions most significantly.

3. Research questions

To continue with this line of enquiry, the present study applies machine-learning classifiers to differentiate between MI and HI, with an emphasis on a multidimensional analysis of syntactic complexity. SHAP values were computed to identify and quantify the most influential syntactic features during the classification, thus enabling an objective and nuanced interpretation of the results. The following research questions guided the investigation:

· To what extent can syntactic complexity metrics serve as discriminative features in machine-learning classifiers for differentiating between MI and HI?

· Which syntactic complexity metrics contribute most significantly to this differentiation, and what patterns do they reveal about the syntactic characteristics of MI and HI?

4. Methodology

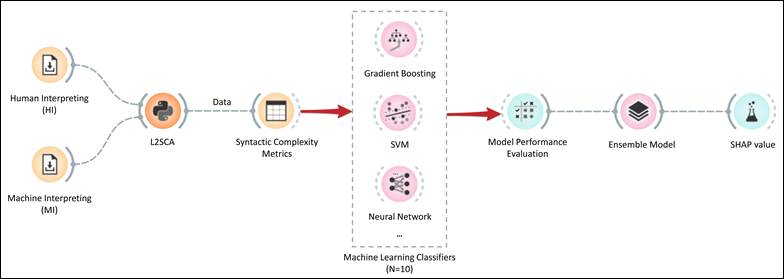

This section details the methods employed to examine the differences in syntactic complexity between MI and HI, including corpus construction, feature extraction and selection, machine-learning classification with ensemble techniques, and the interpretability analysis via SHAP values. Figure 1 illustrates the overall workflow.

Figure 1

Procedures for data collection and analysis

4.1 Corpus construction

To enable a robust comparison of the syntactic complexity patterns in MI and HI, we compiled a comparable English corpus drawn from identical source speeches. The HI sub-corpus consists of interpreted renditions delivered by professional interpreters during China’s annual “Two Sessions”, comprising the National People’s Congress (NPC) and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), spanning the period from 2014 to 2023. These conferences are among the most influential government-initiated events in China; they serve as paramount platforms for communicating the government’s policies and perspectives to both domestic and international audiences (Li, 2018, p. 4). The MI sub-corpus was generated using iFlytek1, a leading multilingual simultaneous interpreting platform that performs automatic speech-to-speech (S2S) translation by combining ASR, MT, and TSS. To ensure direct comparability, iFlytek, renowned for its technological sophistication and real-world applicability, was chosen to process the same source speeches as the HI sub-corpus. This mirrors the approaches in recent MI studies, where commercial systems were evaluated against human baselines in order to assess their ecological validity (Zhang et al., 2025).

To ensure consistency and comparability between HI and MI corpora, we focused exclusively on Chinese-to-English interpreting during question-and-answer (Q&A) sessions. These sessions provide an ideal testing ground for both interpreting modalities because they feature impromptu, specialized communications that replicate authentic interpreting challenges. The source speeches in these Chinese government press conferences present distinctive linguistic and rhetorical features that create specific interpreting demands (Wang, 2012; Yao et al., 2024). Q&A sessions, in particular, are characterized by their formal tone, precise terminology, and structured yet spontaneous exchanges, where spokespersons’ responses tend to be carefully measured, reflecting the political and diplomatic sensitivity of the topics discussed. These characteristics pose unique challenges for both HI and MI, who must operate under complex linguistic features while maintaining accuracy and an appropriate register.

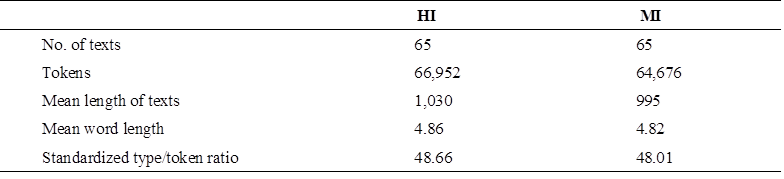

For corpus preparation, transcriptions of the interpreting outputs generated by human interpreters were subjected to manual verification to ensure their fidelity, while machine-generated outputs were preserved in their original form to maintain their authenticity. To control for potential length effects and ensure analytical consistency, we segmented all transcriptions at sentence boundaries, creating comparable text units of approximately 1,000 tokens each. The resulting corpus is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

Description of HI and MI corpora

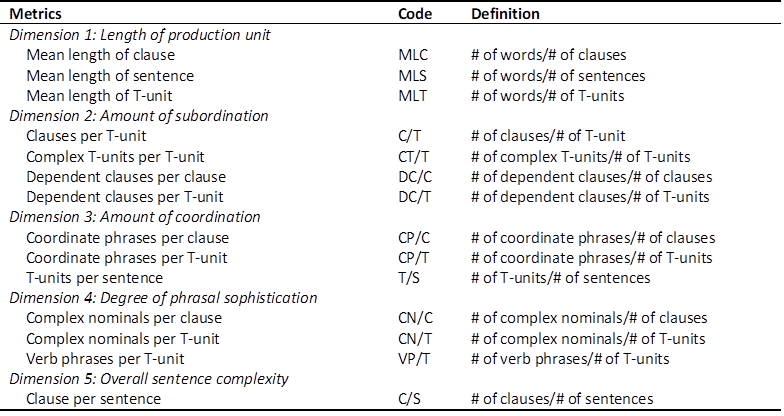

4.2 Syntactic complexity metrics and feature selection

Syntactic complexity was operationalized using the 14 metrics proposed by Lu (2010), which provide a multidimensional lens on clause-level, phrase-level, and overall sentence-level structures. As delineated in Table 2, the metrics were categorized into five dimensions. Lu (2010) provided complete definitions and operational procedures for these metrics. For instance, Hunt (1970) characterized a T-unit as “one main clause plus any subordinate clause or nonclausal structure that is attached to or embedded in it” (p. 4). Following Lu’s (2010) methodological approach, our framework identified three distinct T-unit forms: self-contained independent clauses, coordinated independent clauses functioning collectively, and purposefully segmented sentence components marked by sentence-final punctuation. The metrics were computed automatically via a Python implementation of the L2SCA, which integrates the Stanford parser (Klein & Manning, 2003) to parse the text and Tregex (Levy & Andrew, 2006) to query the parse trees. Although initially designed for the syntactic complexity analysis of second language writing, the L2SCA has been applied effectively in translation and interpreting contexts, enabling the detection and classification of patterns in mediated languages (Chen et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2023; Wang, Liu & Liu, 2024).

Table 2

Syntactic complexity metrics (Lu & Ai, 2015, p. 18)

|

To meet Levshina’s (2015) criterion of at least 15–20 instances per predictor, we implemented a dimension-wise feature selection process that reduces the original 14 indices to five non-redundant high-impact variables, resulting in a conservative 26:1 instance-to-feature ratio. The protocol preserves the conceptual framework of Lu’s (2010) multidimensional model while guarding against overfitting that could arise from excessive parameterization. The procedure unfolded in two sequential stages: first, within each theoretical dimension, we computed Pearson correlations between candidate features and discarded multicollinear features whose absolute correlation coefficient exceeded 0.70 (Dormann et al., 2013). By removing redundant features, we improved the stability of subsequent statistical analyses while preserving the unique information contributed by each dimension. Second, mutual information scores were computed to quantify the extent to which each remaining feature contributed to reducing uncertainty in distinguishing between HI and MI outputs (Vergara & Estévez, 2014). Consequently, the feature with the highest MI score on each dimension was selected and used to train machine-learning classifiers.

4.3 Machine-learning classifiers and evaluation

Following feature selection, we evaluated ten algorithms that span discriminative, probabilistic, generative, and ensemble paradigms to isolate the syntactic features that optimally distinguish MI from HI. The classical set comprised:

(a) linear-discriminative models: logistic regression and linear discriminant analysis (LDA);

(b) boundary-focused model: support vector machines (SVMs);

(c) similarity-based model: k-nearest neighbors (KNN);

(d) probabilistic model: naïve Bayes;

(e) tree-based models: Decision Tree, Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting (GB); and

(f) neural network models: multi-layer perceptron (MLP), a custom deep neural network (DNN).

Specifically, a two-layer feed-forward deep neural network (DNN) implemented in TensorFlow 2.x (ReLU activations, 16→8 units, dropout 0.2, sigmoid output, Adam optimizer) was included. To obtain unbiased performance estimates while tuning the hyperparameters, we adopted a nested 10 × 5 stratified K-fold cross-validation approach (Larracy et al., 2021). We initially established a performance baseline by evaluating all the classifiers with default hyperparameters, then conducted exhaustive grid searches over specified hyperparameter spaces for each classifier in the inner cross-validation loop. This evaluation strategy consisted of an outer tenfold stratified cross-validation for performance evaluation and an inner fivefold loop for hyperparameter tuning.

Based on the performance of the individual classifiers, we developed ensemble models to enhance the overall classification accuracy and robustness, capitalizing on the complementary strengths of diverse algorithms (Sagi & Rokach, 2018; Wang, Liu & Liu, 2024). In particular, we assembled multiple combinations of the highest-performing individual classifiers through a soft voting mechanism. Here, each classifier’s prediction is weighted by its prediction probability, thereby mitigating individual biases and enhancing the decision-making reliability (Rokach, 2010). We experimented with both equal weighting, which assigns uniform influence to all ensemble members for balanced integration, and performance-based weighting, which allocates greater emphasis to classifiers proportional to their validated efficacy. These ensembles were rigorously assessed within the same nested cross-validation framework as individual models, employing identical performance metrics. To facilitate direct and equitable comparisons, these performance metrics included Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC), accuracy, F1-score, precision, and recall (Naidu et al., 2023; Powers, 2011).

4.4 Analysis of feature importance using SHAP values

To elucidate the relative contributions of syntactic complexity features in distinguishing between HI and MI, we performed a post-hoc SHAP analysis to provide insights into both the magnitude and the direction of feature influences, thus augmenting the interpretability of the algorithm (Lundberg & Lee, 2017). Rooted in cooperative game theory, Shapley values were developed to determine the fair allocation of contributions among players in a coalition (Rozemberczki et al., 2022; Shapley, 1953). When applied to machine-learning interpretation, these values quantify each feature’s marginal contribution by averaging its effects over all possible feature coalitions. This approach satisfies several key mathematical properties, including local accuracy, missingness, and consistency (Molnar, 2020), which render it particularly suitable for linguistic analysis where intricate interactions between features are expected.

We implemented SHAP analysis via the KernelExplainer from the Python shap library, which was chosen for its model-agnostic properties that enable the explanation of any black-box classifier (Lundberg & Lee, 2017). The process followed a structured five-step protocol:

1. The selected features were standardized after train-test splitting to eliminate scale-induced bias.

2. The framework was configured to analyse the optimal classifier identified from prior evaluations.

3. A K-means summary of the training data was adopted as the SHAP background, thereby reducing the computational load while preserving the essential distributions, in line with established practice in explainable AI (Lundberg et al., 2020).

4. SHAP values were computed for each feature across all dataset instances, capturing both main effects and potential pairwise interactions among syntactic features.

5. Values were aggregated to yield global metrics such as mean absolute SHAP values for measuring overall feature importance and mean SHAP values for assessing the directional influence of features on predictions.

5. Results

5.1 Feature selection and descriptive statistics

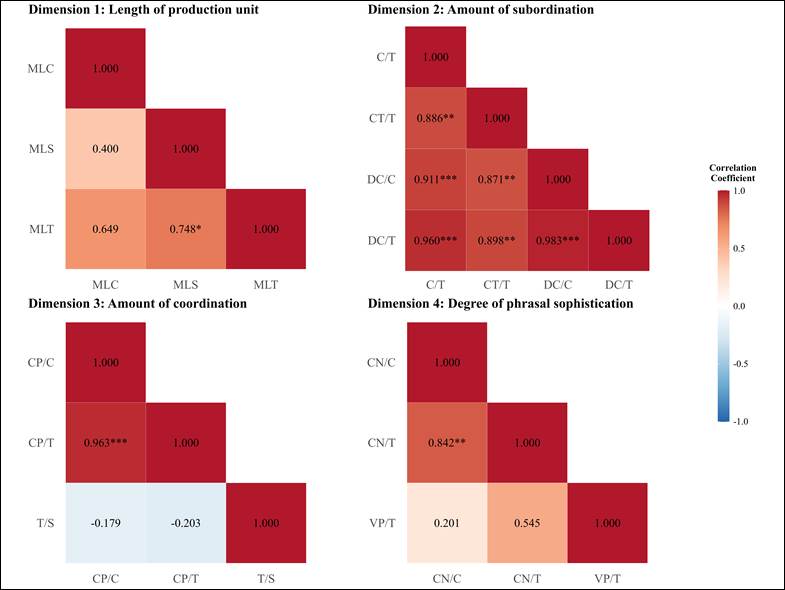

The two-stage feature selection process yielded a refined set of five metrics, one from each of the syntactic complexity dimensions proposed by Lu (2010). In the initial correlation filtering stage, we eliminated multicollinear features within dimensions (threshold: |r| ≥ 0.7) to enhance the model’s stability and interpretability. Figure 2 presents the correlation matrices for Dimensions 1-4, highlighting redundancies such as the strong association between MLS and MLT in Dimension 1 (r = 0.748; MLT removed) and the near-perfect overlap between DC/C and DC/T in Dimension 2 (r = 0.983; DC/T, DC/C, and CT/T removed). Similar patterns emerged in Dimensions 3 and 4, reducing the total features from 14 to 8. Dimension 5, with its single metric (C/S), required no filtering.

Figure 2

Correlation matrices for the four dimensions of syntactic complexity. Stars indicate significance levels (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

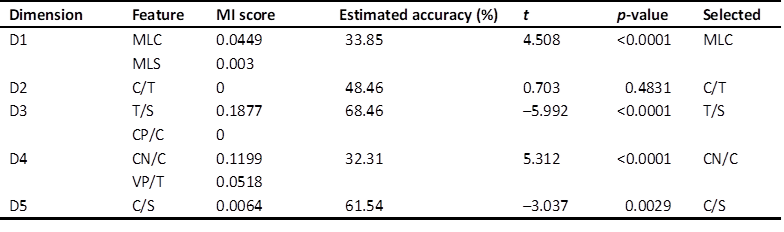

The subsequent mutual information analysis quantified the ability of each remaining feature to discriminate between HI and MI, with higher scores indicating greater informational value (Vergara & Estévez, 2014). Table 3 summarizes the MI scores for all the features, revealing T/S as the most discriminative overall (MI = 0.1877), followed by CN/C (MI = 0.1199). For dimensions with a single post-filtering feature (Dimensions 2 and 5), C/T and C/S were retained despite relatively low MI scores. The final set, including MLC, C/T, T/S, CN/C, and C/S, therefore balances multidimensional coverage with statistical efficiency.

Table 3

Mutual information scores for features after correlation filtering

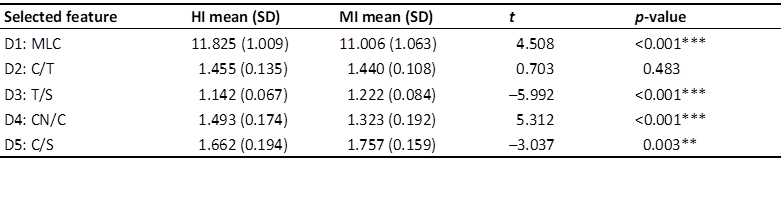

Descriptive statistics and inferential test results for the five selected features in Table 4 also illustrate distributional differences. Figure 3 presents violin plots with embedded boxplots for visualizing these patterns, showing significant divergences in four metrics (p < 0.01), with MI exhibiting lower MLC and CN/C values but higher T/S and C/S values compared to HI. No significant difference emerged for C/T (p = 0.483).

Table 4

Descriptive statistics and statistical significance of selected features

Figure 3

Distribution of selected syntactic complexity features for HI and MI outputs

5.2 Classifier performance in differentiating MI and HI

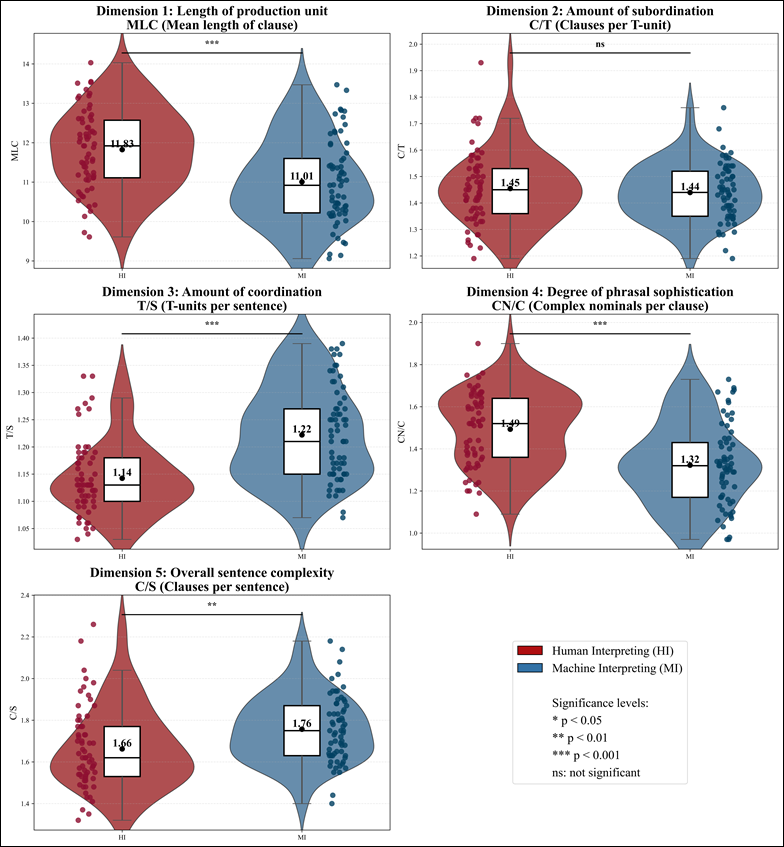

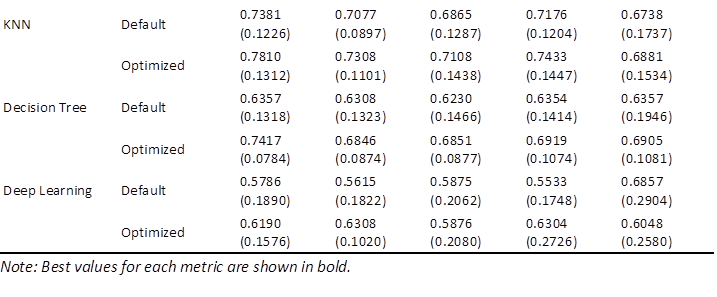

To determine the extent to which syntactic complexity metrics function as discriminative features in machine-learning classifiers, we evaluated ten classifiers under default and fine-tuned hyperparameters, followed by ensemble models combining three top-performing individual classifiers. Table 5 presents the mean performance metrics with standard deviations (SD) across tenfold nested cross-validation, revealing moderate-to-strong classification efficacy and affirming the capability of selected features in capturing modality-specific syntactic patterns.

Table 5

Performance of classifiers for HI vs MI classification

Among individual classifiers, the default SVM stood out as the top performer, achieving the highest level of accuracy (0.7769 ± 0.0939) and a competitive AUC (0.8262 ± 0.1380). Among the tuned variants, the optimized GB achieved the highest AUC (0.8214 ± 0.0858), while the optimized MLP demonstrated superior balance with the top F1 score (0.7370 ± 0.1255) and precision (0.7762 ± 0.1215). Naïve Bayes, conversely, achieved the highest (0.7381 ± 0.1269), highlighting its probabilistic strengths in identifying HI instances. Hyperparameter optimization, implemented via a grid search in the inner cross-validation loop, produced varied effects. Substantial improvements were evident in models such as Decision Tree (AUC increase: 16.7%; accuracy increase: 8.5%). KNN and deep-learning models also benefited, with AUC increases of 5.8% and 7.0%, respectively. However, optimization occasionally led to marginal declines, as seen in SVM (AUC drop: 5.2%; accuracy drop: 5.9%), suggesting that default parameters were already well aligned with the feature space. Models such as LDA and Naïve Bayes showed negligible changes, indicating robustness in their fundamental assumptions.

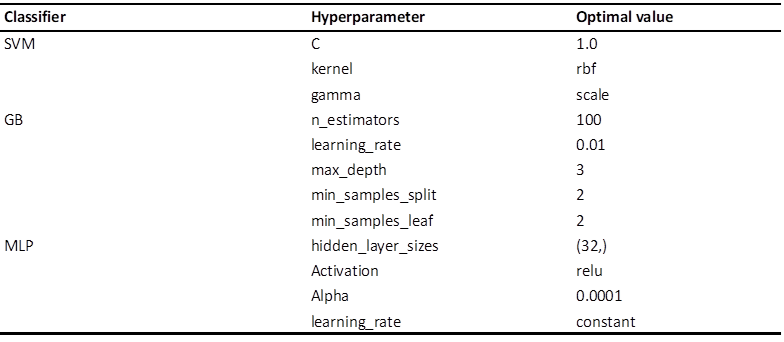

The subsequent analysis focused on identifying the optimal model configurations and exploring the potential of ensemble learning. Table 6 details the optimal hyperparameters for the top three classifiers chosen as the foundation for ensemble methods: default SVM, optimized GB, and optimized MLP. Table 7 presents a detailed comparison of these top individual models against various ensemble configurations. Among them, the equal-weighted SVM + GB + MLP ensemble emerged as the top-performing model in terms of superior discriminatory power, i.e., the highest AUC (0.8429 ± 0.1044), enhanced stability and generalizability (lower SD), and a holistic, unbiased assessment based on different classifiers. Notably, ensembles often displayed greater stability, as evidenced by a lower SD in key metrics compared to standalone models.

Table 6

Optimal hyperparameters for top-performing classifiers

Table 7

Performance of ensemble models for HI vs MI classification

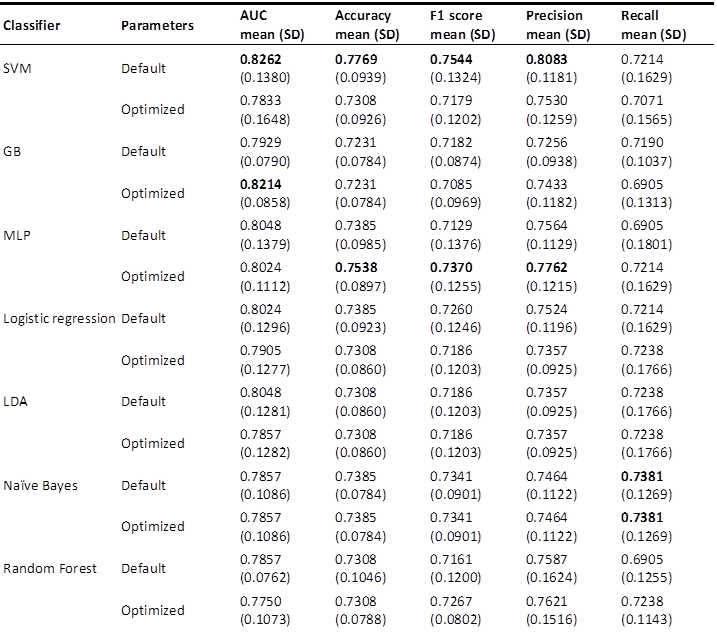

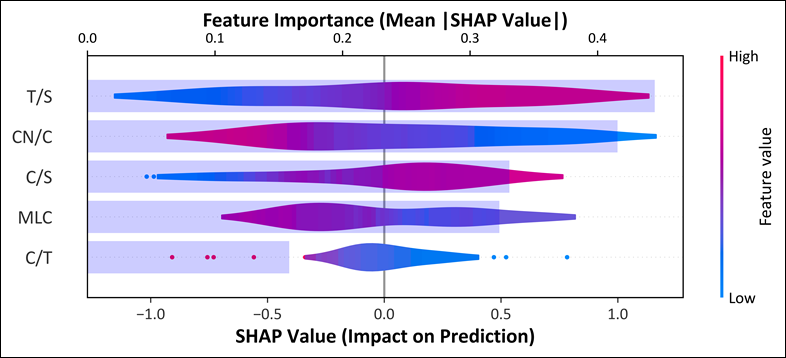

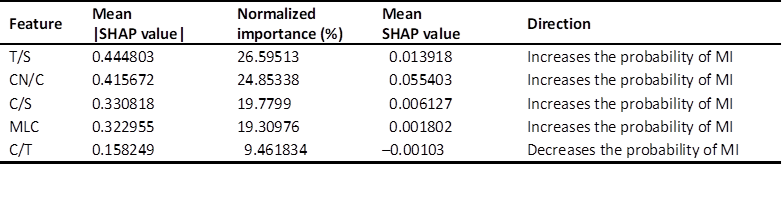

5.3 Distinctive syntactic complexity metrics and patterns

To identify the most salient syntactic complexity metrics and their patterns, we conducted a SHAP analysis on the optimal ensemble model (equal-weighted SVM + GB + MLP). Figure 4 combines a bar plot of mean absolute SHAP values for overall importance and a bee swarm plot illustrating the distribution of individual SHAP values. Table 8 complements this by summarizing the mean absolute SHAP values, normalized importance percentages, mean SHAP values, and directional tendencies.

Figure 4

SHAP summary plot for the best-performing model: SVM + GB + MLP (Equal Weights)

Table 8

Feature importance and impact direction based on SHAP analysis

The analysis establishes a clear hierarchy of feature importance, with four metrics predominantly driving classifications towards MI and one towards HI, thereby illuminating modality-specific syntactic characteristics. Leading this hierarchy is T/S, which accounts for 26.6% of the model’s discriminative power. Its positive mean SHAP value indicates a systematic bias towards MI classification, with higher T/S values denoting increased coordination through independent T-units within sentences. Closely following is CN/C, which accounts for 24.9% of the model’s discriminative power. This metric exhibits the strongest positive directional impact, underscoring MI’s tendency towards heightened phrasal sophistication through complex noun phrases. C/S and MLC occupy mid-tier positions, with comparable importance levels at 19.8% and 19.3%, respectively – both of them producing positive mean SHAP values and direct predictions towards MI. These patterns highlight MI’s tendency towards denser and more complex clausal constructions. In contrast, C/T exerts the least influence, comprising only 9.5% of the model’s explanatory weight, and stands alone with a negative mean SHAP value. This orientation implies that higher C/T values, signifying increased subordination within T-units, decrease the likelihood of an MI classification, in this way favouring HI.

Collectively, these findings delineate a coherent pattern: MI outputs are characterized by elevated values in coordination (T/S), phrasal sophistication (CN/C), overall sentence complexity (C/S), and production unit length (MLC). This suggests that MI outputs have a propensity for structural density and elaboration. In contrast, HI outputs display a higher level of subordination (C/T), one characterized by more integrated embedding within T-units.

6. Discussion

6.1 Syntactic complexity as an effective discriminator

This study employed machine-learning classifiers to differentiate between MI and HI based on multidimensional syntactic complexity metrics. These classifiers achieved substantial discriminative performance and revealed distinctive syntactic patterns between the two modalities. The results demonstrate that syntactic complexity metrics serve as moderately to highly effective discriminators between MI and HI, with the optimal ensemble model (equal-weighted SVM + GB + MLP) achieving an AUC of 84.29% and an accuracy of 76.15%. These performance metrics substantiate our hypothesis that systematic syntactic differences exist between computational and human-language mediation, extending beyond surface-level variations to reflect fundamental divergences in processing mechanisms.

Methodologically, this study represents one of the first attempts to apply machine-learning classifiers to interpreting studies, where the classification performance aligns with that reported in comparable studies on translated language. Whereas Wang, Liu and Liu (2024) achieved a higher level of discrimination (AUC = 99.3%) using similar L2SCA metrics, their task involved distinguishing between linguistically distant categories, specifically distinguishing between translated and non-translated corporate texts. Our more moderate results reflect the intrinsic challenge of distinguishing between mediated language variants that share essential features, specifically real-time bilingual processing constrained by cognitive or computational limitations. Furthermore, the superiority of ensemble models over individual classifiers corroborates the established machine-learning principles regarding the variance in reduction and the exploitation of complementary strengths (Rokach, 2010; Sagi & Rokach, 2018; Wang, Liu & Liu, 2024). Consequently, this finding extends previous interpreting studies that relied predominantly on traditional statistical methods or individual classification models.

The dimension-wise feature selection was essential to ensuring reliable classification results without sacrificing model interpretability. By reducing multicollinearity and selecting maximally informative features from each theoretical dimension, we preserved Lu’s (2010) multidimensional framework while optimizing its statistical efficiency. This approach served to overcome the limitations identified in previous studies, where high correlations among syntactic metrics may have confounded the results (Norris & Ortega, 2009; Pan & Zhou, 2024). The mutual information scores revealed substantial variability in discriminative power across dimensions, with coordination (T/S, MI = 0.1877) and phrasal sophistication (CN/C, MI = 0.1199) emerging as particularly informative, whereas subordination (C/T, MI = 0) showed minimal univariate discrimination – a pattern that would be obscured by the inclusion of holistic features.

6.2 Distinctive syntactic profiles of MI and HI

The SHAP analysis revealed a clear hierarchy of feature importance and directional patterns, establishing distinct syntactic features for MI and HI. These patterns illuminate fundamental differences in processing mechanisms, with MI exhibiting a propensity for structural density through coordination and HI demonstrating a preference for hierarchical integration through subordination. The dominance of T/S as the primary discriminator reveals how architectural constraints shape language production. MI’s significantly higher T/S values indicate a systematic preference for paratactic structures, with sequences of independent clauses more connected through coordination rather than subordination. This finding corroborates Zhang et al.’s (2025) observations while extending their analysis by quantifying the discriminative power of coordination patterns.

The cascading architecture of MI systems—a multi-stage processing structure where each component’s output feeds sequentially into the next—fundamentally shapes their syntactic output. To balance translation accuracy and system latency, as Fantinuoli (2025) elucidates, the sequential pipeline involving ASR, MT, and TSS components necessitates modular processing, segmenting incoming speech into discrete chunks for real-time translation. Each component operates in a limited local context: ASR segments audio based on acoustic boundaries; MT processes these segments independently, and TSS generates output without having access to the global discourse structure. This architectural constraint manifests linguistically as what Schaeffer and Carl (2014) term “horizontal translation”, a process that prioritizes automatic translinguistic equivalences over conceptual integration. The horizontal processing paradigm reflects deeper computational limitations. Downie’s (2020) criticism that MI operates on the premise that “there are only words and nothing but words” (p. 37) captures the fundamental absence of a conceptual substrate in machine processing. Without access to world knowledge or discourse models, MI systems default to surface-level transformations that preserve local coherence while sacrificing global integration.

In contrast, human interpreters engage in “vertical translation”, a conceptually mediated process that transcends linguistic form in order to access meaning. This vertical dimension, as Setton (1999) demonstrates, involves constructing mental models that integrate linguistic input with world knowledge, situational context, and communicative intent. Such conceptual mediation enables the subordination to be strategically deployed, as evidenced by C/T emerging as the sole metric with a negative directional effect. Although C/T contributed only 9.5% to overall discrimination, its oppositional pattern illuminates a crucial dimension of human expertise. While MI excels at generating coordinate structures, human interpreters demonstrate superior ability to create hierarchically integrated structures through embedded subordination. The subordination advantage could stem from human interpreters’ ability to engage in anticipatory processing (Setton, 1998; Van Besien, 1999). This anticipation, difficult for current MI systems operating in the local context, enables a commitment to complex hierarchical structures with confidence in successful integration. The top-down planning capacity inherent in human cognition therefore facilitates syntactic choices that optimize both information density and processing efficiency.

Beyond the coordination–subordination divide, three additional metrics, including CN/C (24.9%), C/S (19.8%), and MLC (19.3%), exhibited positive effects on MI classification, revealing multifaceted patterns of syntactic elaboration. The findings partially corroborate previous observations about the elevated complexity in machine-generated language (Liu & Liang, 2024; Zhang et al., 2025) while also revealing important nuances. The positive effect of C/S on MI classification indicates the accumulation of clauses within sentence boundaries in MI outputs; this could be due to the absence of working-memory constraints that limit human clausal density. Similarly, elevated MLC values in MI suggest longer individual clauses unconstrained by articulatory planning that naturally segment human speech. Paradoxically, CN/C displayed a positive contribution to MI classification despite MI’s lower absolute values. This contradiction is resolved when considering the role of metric in the broader feature space. The positive SHAP value indicates that, when accounting for other variables, increases in CN/C make MI classification more probable. This statistical relationship to some extent reflects MI’s inconsistent deployment of complex nominals, alternating between over-simplification and inappropriate elaboration, compared to HI’s strategic and consistent use of nominal complexity for information packaging.

Collectively, these observed distinctions underscore the essential differences in the processing mechanisms employed by human interpreters and computational algorithms. Human interpreters often operate under what Gile (1995/2009) terms the “tightrope hypothesis”, constantly approaching cognitive saturation due to competing demands on attention, memory, and production. These constraints include temporal pressure, working-memory limitations, linearity requirements, and knowledge asymmetries (Gumul, 2017). Traditional views interpret such constraints as impediments, predicting universal simplification in interpreted language (Bizzoni et al., 2020; Laviosa, 2002; Liang et al., 2019; Lv & Liang, 2019). However, our findings suggest that cognitive constraints may, in turn, facilitate the development of sophisticated linguistic strategies, reflecting a more nuanced understanding of their role. Operating within tight capacity limits, human interpreters develop optimized solutions that balance multiple demands. The higher subordination rates in HI demonstrate the way in which expertise involves not transcending constraints but optimizing within them. Strategic simplification in some dimensions (e.g., lower clausal density) creates cognitive space for complexity in others (e.g., hierarchical integration). This trade-off reflects what Seeber (2011) identifies as “cognitive load management” regarding the strategic allocation of limited resources to maximize communicative effectiveness. Conversely, MI systems operate without such constraints, possessing virtually unlimited working memory and processing capacity. This computational advantage enables them to generate complex structures without experiencing capacity limitations or fatigue. However, the absence of cognitive constraints paradoxically leads to less effective output. Their outputs reflect statistical optimization rather than genuine linguistic competence, which results in a homogeneous output that prioritizes formal complexity over functional adequacy (Vanmassenhove et al., 2021).

To summarize, the analysis reveals two complementary syntactic strategies: MI employs an “additive complexity” approach characterized by sequential processing without overarching planning, whereas HI demonstrates “integrative complexity” through human-specific conceptual mediation. This process facilitates the construction of abstract meaning representations that effectively guide syntactic encoding. These complementary profiles resonate with the observation of Bizzoni et al. (2020) that MT systems fail to replicate cognitively induced patterns in HI, in which the training dataset and the algorithm bias may play a role (Graham et al., 2019; Vanmassenhove et al., 2019, 2021; Zhang & Toral, 2019). Consequently, our analysis extends beyond the simple presence or absence of simplification to reveal qualitatively different complexity strategies, highlighting a clear and practical division of labor for effective human-computer collaboration in interpreting.

7. Conclusion

This study employed machine-learning classifiers to investigate syntactic complexity as a discriminator between MI and HI, responding to a critical gap in our understanding of the way computational and human cognitive systems diverge in real-time language mediation. Through a systematic analysis of multidimensional syntactic features, we achieved three principal contributions: demonstrating the discriminative power of syntactic complexity metrics, revealing the distinctive syntactic characteristics of MI and HI, and providing empirically grounded insights for both theoretical advancement and practical application.

Findings offer valuable insights into both theoretical understanding and practical applications. For interpreting studies, they necessitate reconceptualizing translation universals when machine processing enters the equation. Traditional conceptualizations that assume human agency to be a constant must be revised to accommodate state-of-the-art technologies, such as MI’s mechanical complexification versus HI’s strategic optimization. For MI system developers, the importance hierarchy of the SHAP-derived features offers concrete optimization targets. For interpreter training programmes, understanding MI’s linguistic features becomes crucial because human–machine collaboration increasingly characterizes professional practice. Notably, the moderate accuracy of classification also carries nuanced implications, since a 23.85% error rate reveals zones of convergence where MI and HI outputs become indistinguishable syntactically, pointing to possible areas for effective human–machine collaboration.

Several limitations should be acknowledged in order to contextualize our findings appropriately. First, this study is limited to a relatively small and domain-specific corpus containing Chinese-to-English interpreting, which may not capture the full range of linguistic diversity present in other interpreting settings or language pairs. Future research should consider expanding the corpus to include various domains, genres, and language combinations to enhance the generalizability of the results. Moreover, our exclusive focus on syntactic complexity metrics represents only one aspect of linguistic analysis. Other linguistic features – such as lexical diversity, semantic cohesion, and pragmatic markers – may also play a significant role in differentiating MI from HI. Third, we acknowledge the limitations in the precise internal architecture of the MI system, such as processing latencies and segmentation strategies (Fantinuoli, 2025). A deeper understanding of these internal workings would be beneficial for a more nuanced interpretation of the sources of syntactic variation between machine and human outputs.

Finally, one methodological consideration concerns the interpreting modes compared. The MI system processed source speeches continuously, whereas human interpreters performed consecutive interpreting. Despite Fantinuoli’s (2023) acknowledgement that the translation process in MI systems can be either simultaneous or consecutive, commercial MI systems still blur the traditional modal distinctions – their ASR-MT-TSS pipeline remains architecturally consistent whether they are processing continuous or segmented input. This architectural invariance suggests that the syntactic patterns we identified reflect fundamental human–machine differences rather than mode-specific effects. Nevertheless, to further disentangle mode-specific effects from system-based variation, future research could directly compare MI and HI within identical interpreting modes in order to isolate modal influences on syntactic variation.

Endnote

1 See the website: https://tongchuan.iflyrec.com/

References

Baker, M. (1993). Corpus linguistics and translation studies: Implications and applications. In M. Baker, G. Francis, & E. Tognini-Bonelli (Eds.), Text and technology: In honour of John Sinclair (pp. 233–250). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/z.64.15bak

Baroni, M., & Bernardini, S. (2006). A new approach to the study of translationese: Machine-learning the difference between original and translated text. Literary and Linguistic Computing, 21(3), 259–274. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqi039

Biber, D., Gray, B., & Poonpon, K. (2011). Should we use characteristics of conversation to measure grammatical complexity in L2 writing development? TESOL Quarterly, 45(1), 5–35. https://doi.org/10.5054/tq.2011.244483

Bizzoni, Y., Juzek, T. S., España-Bonet, C., Dutta Chowdhury, K., van Genabith, J., & Teich, E. (2020). How human is machine translationese?: Comparing human and machine translations of text and speech. In Proceedings of the 17th international conference on spoken language translation (pp. 280–290). Association for Computational Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2020.iwslt-1.34

Braun, S. (2015). Remote interpreting. In H. Mikkelson & R. Jourdenais (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of interpreting (pp. 352–367). Routledge.

Chen, J., Li, D., & Liu, K. (2024). Unraveling cognitive constraints in constrained languages: A comparative study of syntactic complexity in translated, EFL, and native varieties. Language Sciences, 102, Article 101612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2024.101612

Chen, S., & Kruger, J.-L. (2023). The effectiveness of computer-assisted interpreting: A preliminary study based on English–Chinese consecutive interpreting. Translation and Interpreting Studies, 18(3), 399–420. https://doi.org/10.1075/tis.21036.che

Chen, S., & Kruger, J.-L. (2024). Visual processing during computer-assisted consecutive interpreting. Interpreting, 26(2), 231–252. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.00104.che

Cheung, A. K. F. (2024). Cognitive load in remote simultaneous interpreting: Place name translation in two Mandarin variants. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), Article 1238. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03767-y

De Clercq, O., de Sutter, G., Loock, R., Cappelle, B., & Plevoets, K. (2021). Uncovering machine translationese using corpus analysis techniques to distinguish between original and machine-translated French. Translation Quarterly, 101, 21–45. https://hal.science/hal-03406287

Defrancq, B., & Fantinuoli, C. (2021). Automatic speech recognition in the booth: Assessment of system performance, interpreters’ performances and interactions in the context of numbers. Target, 33(1), 73–102. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.19166.def

Dormann, C. F., Elith, J., Bacher, S., Buchmann, C., Carl, G., Carré, G., Marquéz, J. R. G., Gruber, B., Lafourcade, B., Leitão, P. J., Münkemüller, T., McClean, C., Osborne, P. E., Reineking, B., Schröder, B., Skidmore, A. K., Zurell, D., & Lautenbach, S. (2013). Collinearity: A review of methods to deal with it and a simulation study evaluating their performance. Ecography, 36(1), 27–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2012.07348.x

Downie, J. (2020). Interpreters vs machines. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003001805

Downie, J. (2023). Where is it all going?: Technology, economic pressures and the future of interpreting. In G. C. Pastor & B. Defrancq (Eds.), Interpreting technologies: Current and future trends (pp. 277–301). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/ivitra.37.11dow

Fantinuoli, C. (2018). Interpreting and technology: The upcoming technological turn. In C. Fantinuoli (Ed.), Interpreting and technology (pp. 1–12). Language Science Press.

Fantinuoli, C. (2023). The emergence of machine interpreting. European Society for Translation Studies, 62, 10. https://www.claudiofantinuoli.org/docs/ESTNL_May_2023.pdf

Fantinuoli, C. (2025). Machine interpreting. In E. Davitti, T. Korybski, & S. Braun (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of interpreting, technology and AI (pp. 209–226). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003053248-16

Fantinuoli, C., & Prandi, B. (2021). Towards the evaluation of automatic simultaneous speech translation from a communicative perspective. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2103.08364

Gile, D. (1995/2009). Basic concepts and models for interpreter and translator training. John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.8

Graham, Y., Haddow, B., & Koehn, P. (2019). Translationese in machine translation evaluation. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1906.09833

Gumul, E. (2017). Explicitation in simultaneous interpreting: A study into explicitating behaviour of trainee interpreters. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego.

Hu, H., & Kübler, S. (2021). Investigating translated Chinese and its variants using machine learning. Natural Language Engineering, 27(3), 339–372. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1351324920000182

Hunt, K. W. (1970). Recent measures in syntactic development. In M. Lester (Ed.), Readings in applied transformation grammar. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Ilisei, I., Inkpen, D., Corpas Pastor, G., & Mitkov, R. (2010). Identification of translationese: A machine learning approach. In A. Gelbukh (Ed.), Computational linguistics and intelligent text processing. CICLing 2010 (pp. 503–511). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-12116-6_43

Jiang, Y., & Niu, J. (2022). A corpus-based search for machine translationese in terms of discourse coherence. Across Languages and Cultures, 23(2), 148–166. https://doi.org/10.1556/084.2022.00182

Klein, D., & Manning, C. D. (2003). Accurate unlexicalized parsing. In Proceedings of the 41st annual meeting of the association for computational linguistics (pp. 423–430). Association for Computational Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.3115/1075096.1075150

Krüger, R. (2020). Explicitation in neural machine translation. Across Languages and Cultures, 21(2), 195–216. https://doi.org/10.1556/084.2020.00012

Kyle, K., & Crossley, S. A. (2018). Measuring syntactic complexity in L2 writing using fine‐grained clausal and phrasal indices. The Modern Language Journal, 102(2), 333–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12468

Larracy, R., Phinyomark, A., & Scheme, E. (2021). Machine learning model validation for early stage studies with small sample sizes. In 2021 43rd annual international conference of the IEEE engineering in medicine & biology society (EMBC) (pp. 2314–2319). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/EMBC46164.2021.9629697

Laviosa, S. (1998). The corpus-based approach: A new paradigm in translation studies. Meta, 43(4), 474–479. https://doi.org/10.7202/003424ar

Laviosa, S. (2002). Corpus-based translation studies: Theory, findings, applications. Rodopi. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004485907

Levshina, N. (2015). How to do linguistics with R: Data exploration and statistical analysis. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1075/z.195

Levy, R., & Andrew, G. (2006). Tregex and Tsurgeon: Tools for querying and manipulating tree data structures. In N. Calzolari, K. Choukri, A. Gangemi, B. Maegaard, J. Mariani, J. Odijk, & D. Tapias (Eds.), Proceedings of the fifth international conference on language resources and evaluation (pp. 2231–2234). European Language Resources Association. http://www.lrec-conf.org/proceedings/lrec2006/pdf/513_pdf.pdf

Li, R., Liu, K., & Cheung, A. K. F. (2025). Exploring the impact of intermodal transfer on simplification: Insights from signed language interpreting, subtitle translation, and native speech in TED talks. Language Sciences, 110, Article 101726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2025.101726

Li, X. (2018). The reconstruction of modality in Chinese–English government press conference interpreting: A corpus-based study. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5169-2

Liang, J., Lv, Q., & Liu, Y. (2019). Quantifying interpreting types: Language sequence mirrors cognitive load minimization in interpreting tasks. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, Article 285. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00285

Liu, K., & Afzaal, M. (2021). Syntactic complexity in translated and non-translated texts: A corpus-based study of simplification. PLoS ONE, 16(6), Article e0253454. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253454

Liu, K., Ye, R., Liu, Z., & Ye, R. (2022). Entropy-based discrimination between translated Chinese and original Chinese using data mining techniques. PLoS ONE, 17(3), Article e0265633. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265633

Liu, Y., Cheung, A. K. F., Liu, K. (2023). Syntactic complexity of interpreted, L2 and L1 speech: A constrained language perspective. Lingua, 286, Article 103509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2023.103509

Liu, Y., & Liang, J. (2024). Multidimensional comparison of Chinese–English interpreting outputs from human and machine: Implications for interpreting education in the machine-translation age. Linguistics and Education, 80, Article 101273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2024.101273

Lu, X. (2010). Automatic analysis of syntactic complexity in second language writing. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 15(4), 474–496. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.15.4.02lu

Lu, X. (2022). Yiyuan yu jiqi hanying tongsheng chuanyi zhiliang he guocheng duibi yanjiu [Comparing the quality and processes of Chinese–English simultaneous interpreting by interpreters and a machine]. Foreign Language Teaching and Research (bimonthly), 54(4), 600–610 + 641. https://doi.org/10.19923/j.cnki.fltr.2022.04.011

Lu, X. (2023). Rengong yu jiqi tongsheng chuanyi: Renzhi guocheng, nengli, zhiliang duibi yu zhanwang [Human and machine simultaneous interpreting: Comparative analysis and prospects of cognitive processes, competence, and quality]. Chinese Translators Journal, 44(3), 135–141.

Lu, X., & Ai, H. (2015). Syntactic complexity in college-level English writing: Differences among writers with diverse L1 backgrounds. Journal of Second Language Writing, 29, 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2015.06.003

Lundberg, S. M., Erion, G., Chen, H., DeGrave, A., Prutkin, J. M., Nair, B., Katz, R., Himmelfarb, J., Bansal, N., & Lee, S.-I. (2020). From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nature Machine Intelligence, 2, 56–67. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-019-0138-9

Lundberg, S. M., & Lee, S. I. (2017). A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 30, 4765–4774. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1705.07874

Luo, J., & Li, D. (2022). Universals in machine translation?: A corpus-based study of Chinese–English translations by WeChat Translate. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 27(1), 31–58. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.19127.luo

Lv, Q., & Liang, J. (2019). Is consecutive interpreting easier than simultaneous interpreting?: A corpus-based study of lexical simplification in interpretation. Perspectives, 27(1), 91–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2018.1498531

Molnar, C. (2020). Interpretable machine learning: A guide for making black box models explainable. Lulu.com.

Naidu, G., Zuva, T., & Sibanda, E. M. (2023). A review of evaluation metrics in machine learning algorithms. In R. Silhavy & P. Silhavy (Eds.), Artificial intelligence application in networks and systems (pp. 15–25). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-35314-7_2

Norris, J. M., & Ortega, L. (2009). Towards an organic approach to investigating CAF in instructed SLA: The case of complexity. Applied Linguistics, 30(4), 555–578. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amp044

Ortega, L. (2003). Syntactic complexity measures and their relationship to L2 proficiency: A research synthesis of college‐level L2 writing. Applied Linguistics, 24(4), 492–518. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/24.4.492

Pan, F., & Zhou, X. (2024). Are research articles becoming more syntactically complex?: Corpus-based evidence from research articles in applied linguistics and biology (1965–2015). Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 42(4), 554–571. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073614.2024.2333280

Pöchhacker, F. (2024). Is machine interpreting interpreting? Translation Spaces. https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.23028.poc

Popović, M., Lapshinova-Koltunski, E., & Koponen, M. (2023). Computational analysis of different translations: By professionals, students and machines. In Proceedings of the 24th annual conference of the European association for machine translation (pp. 365–374). European Association for Machine Translation. https://aclanthology.org/2023.eamt-1.36

Powers, D. M. (2011). Evaluation: From precision, recall and F-measure to ROC, informedness, markedness and correlation. Journal of Machine Learning Technologies, 2(1), 37–63. https://doi.org/10.9735/2229-3981

Prandi, B. (2023). Computer-assisted simultaneous interpreting: A cognitive-experimental study on terminology. Language Science Press.

Rokach, L. (2010). Ensemble-based classifiers. Artificial Intelligence Review, 33(1–2), 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-009-9124-7

Rozemberczki, B., Watson, L., Bayer, P., Yang, H.-T., Kiss, O., Nilsson, S., & Sarkar, R. (2022). The Shapley value in machine learning. In L. De Raedt (Ed.), Proceedings of the 31st international joint conference on artificial intelligence, IJCAI-ECAI 2022 (pp. 5572–5579). International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence Organization. https://doi.org/10.24963/ijcai.2022/778

Roziner, I., & Shlesinger, M. (2010). Much ado about something remote: Stress and performance in remote interpreting. Interpreting, 12(2), 214–247. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.12.2.05roz

Schaeffer, M., & Carl, M. (2014). Measuring the cognitive effort of literal translation processes. In U. Germann, M. Carl, P. Koehn, G. Sanchis-Trilles, F. Casacuberta, R. Hill, & S. O’Brien (Eds.), Proceedings of the workshop on humans and computer-assisted translation (pp. 29–37). Association for Computational Linguistics. https://aclanthology.org/W14-0306/

Sagi, O., & Rokach, L. (2018). Ensemble learning: A survey. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 8(4), Article e1249. https://doi.org/10.1002/widm.1249

Seeber, K. G. (2011). Cognitive load in simultaneous interpreting: Existing theories: New models. Interpreting, 13(2), 176–204. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.13.2.02see

Setton, R. (1998). Meaning assembly in simultaneous interpreting. Interpreting, 3(2), 163–199. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.3.2.03set

Setton, R. (1999). Simultaneous interpretation: A cognitive-pragmatic analysis. John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.28

Sen, J. (2021). Machine learning: Algorithms, models, and applications. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.94615

Shapley, L. S. (1953). A value for n-person games. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400881970-018

Van Besien, F. (1999). Anticipation in simultaneous interpretation. Meta, 44(2), 250–259. https://doi.org/10.7202/004532ar

Vanmassenhove, E., Shterionov, D., & Gwilliam, M. (2021). Machine translationese: Effects of algorithmic bias on linguistic complexity in machine translation. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2102.00287

Vanmassenhove, E., Shterionov, D., & Way, A. (2019). Lost in translation: Loss and decay of linguistic richness in machine translation. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1906.12068

Vergara, J. R., & Estévez, P. A. (2014). A review of feature selection methods based on mutual information. Neural Computing and Applications, 24, 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-013-1368-0

Vieira, L. N. (2018). Automation anxiety and translators. Translation Studies, 13(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2018.1543613

Wang, B. (2012). A descriptive study of norms in interpreting: Based on the Chinese–English consecutive interpreting corpus of Chinese premier press conferences. Meta, 57(1), 198–212. https://doi.org/10.7202/1012749ar

Wang, X., & Wang, C. (2019). Can computer-assisted interpreting tools assist interpreting? Transletters. International Journal of Translation and Interpreting, 3, 109–139. https://journals.uco.es/tl/article/view/11575

Wang, Z., Cheung, A. K. F., & Liu, K. (2024). Entropy-based syntactic tree analysis for text classification: A novel approach to distinguishing between original and translated Chinese texts. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 39(3), 984–1000. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqae030

Wang, Z., Liu, M., & Liu, K. (2024). Utilizing machine Learning techniques for classifying translated and non-translated corporate annual reports. Applied Artificial Intelligence, 38(1), Article 2340393. https://doi.org/10.1080/08839514.2024.2340393

Wang, Z., Liu, K., & Moratto, R. (2023). A corpus-based study of syntactic complexity of translated and non-translated chairman’s statements. Translation & Interpreting: The International Journal of Translation and Interpreting Research, 15(1), 135–151. https://doi.org/10.12807/ti.115201.2023.a07

Xie, R., Yao, Y., Zhang, W., & Cheung, A. K. F. (2025). Language interference in Mandarin Chinese–English simultaneous interpreting: Insights from multi-dimensional syntactic complexity. Lingua, 325, Article 104005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2025.104005

Xu, J., & Li, J. (2021). A syntactic complexity analysis of translational English across genres. Across Languages and Cultures, 22(2), 214–232. https://doi.org/10.1556/084.2021.00015

Yao, Y., Li, D., Huang, Y., & Sang, Z. (2024). Linguistic variation in mediated diplomatic communication: A full multi-dimensional analysis of interpreted language in Chinese regular press conferences. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), Article 1409. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03967-6

Zhang, M., & Toral, A. (2019). The effect of translationese in machine translation test sets. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1906.08069

Zhang, W., & Xie, R. (2025). Monolingual versus bilingual captioning: An ergonomic perspective on computer-assisted simultaneous interpreting. Interpreting and Society: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 5(2), 131–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/27523810251323943

Zhang, W., Xie, R., Yao, Y., & Li, D. (2025). Lexico-syntactic complexity in machine interpreting: A corpus-based comparison with human interpreting and translation. International Journal of Applied Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijal.12830

Zhang, W., Yao, Y., Xie, R., & Li, D. (2025). Can artificial intelligence mirror the human’s emotions?: A comparative sentiment analysis of human and machine interpreting in press conferences. Behaviour & Information Technology, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929x.2025.2546975