Eye-tracking visual attention of professional interpreters during technology-assisted simultaneous interpreting

Wenchao Su

Guangdong University of Foreign Studies

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9851-9753

Defeng Li

University of Macau

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9316-3313

Abstract

This study investigated the ways in which professional interpreters’ visual attention is captured by real-time source text captions generated by automatic speech recognition (ASR) and real-time target text subtitles generated by automatic speech translation (AST) – both of which are presented in parallel during simultaneous interpreting (SI). Using eye-tracking data, we examined whether attention to ASR and AST varies according to the interpreting direction (L1–L2 vs L2–L1) and how it relates to interpreting accuracy. The findings indicate that the ASR captions captured more attention than the AST subtitles, especially in the L1–L2 direction. In the L2–L1 direction, greater attention to AST subtitles in the interpreters’ L1 (Chinese) was linked to a greater level of accuracy. These findings were explained by the interaction of bottom-up and top-down factors. Insights into these attention patterns could possibly inform the design of tailored training sessions to equip interpreters better for SI in technology-assisted environments.

Keywords: technology-assisted simultaneous interpreting, visual attention, professional interpreters, student interpreters, eye-tracking, directionality

1. Introduction

Simultaneous interpreting (SI) is a demanding cognitive task that requires strategic attention management. The ways in which interpreters’ attention is captured during this process is closely related to interpreting accuracy (Lambert, 2004; Gile, 2009). With the advent of new technologies, professional interpreters are increasingly using automatic speech recognition (ASR) and automatic speech translation (AST) tools to aid their practice (e.g., Fantinuoli, 2022, 2023; Lu, 2022, 2023).

ASR transcribes spoken source language (SL) into written text. To define the translation technology used in our study, we considered the terms machine interpreting (MI) and machine translation (MT). MI typically delivers spoken output and is therefore not entirely suitable to our study, because the interpreters in our cohort read real-time visual translations. Similarly, MT does not describe our study’s setup accurately, because it does not imply the display of real-time translation. Therefore, following Pöchhacker (2024), we use the term “automatic speech translation” (or “AST”) specifically to refer to the real-time translation of source speech transcripts from one language to another. These new technologies in SI raise questions about the ways in which ASR captions and AST subtitles could draw interpreters’ visual attention and affect their interpreting accuracy.

Furthermore, the direction of interpreting, whether from L1 to L2 or from L2 to L1, can influence the manner in which interpreters’ attention is captured (Su & Li, 2020). Technology-assisted modes may add complexity, because interpreters need to navigate and focus their attention between the source speech, the ASR-generated source text, the AST-generated target text, and their own output. We use the term “technology-assisted interpreting” to emphasize the integration of real-time tools, specifically ASR and AST, in the interpreting process. Unlike computer-assisted interpreting (CAI), which often provides partial or static support such as terminology databases or pre-translated segments, ASR and AST offer continuous and dynamic assistance by transcribing and translating the full source speech in real-time. This distinction supports our use of the broader term “technology-assisted interpreting”, which reflects more accurately the real-time and comprehensive nature of the tools used in our study.

Previous studies have examined the ways in which technologies such as ASR and AST affect interpreters’ cognitive load and output accuracy in SI, indicating that these tools can enhance accuracy while reducing cognitive load (Defrancq & Fantinuoli, 2021; Li & Chmiel, 2024; Su & Li, 2024; Yuan & Wang, 2023). These studies primarily investigated whether the use of technologies affects the accuracy of interpreting and also interpreters’ cognitive load. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies to date have focused on the way professional interpreters’ visual attention is captured by ASR captions and AST subtitles during SI in both the L1–L2 and the L2–L1 directions.

Therefore, further empirical investigation is necessary to explore the way in which visual attention is captured by ASR and AST throughout the process of SI, where both are shown in parallel. Understanding these visual attention patterns can yield concrete recommendations for interpreters. For instance, these insights can help interpreters refine their focus-shifting techniques and manage their interactions with ASR captions and AST subtitles. As a result, the study’s findings may help interpreters to manage the complexities of technology-assisted SI more effectively and to improve their levels of accuracy and confidence. The present study attempted to fill this gap by investigating professional interpreters’ visual attention during technology-assisted SI from Chinese to English (L1–L2) and English to Chinese (L2–L1); it focused on the interaction of visual attention and interpreting direction and the relationship between interpreting accuracy and visual attention.

2. Visual attention and interpreting accuracy in simultaneous interpreting

Visual attention is the way we focus on certain parts of what we see, which allows us to find, recognize, and make sense of objects in our environment (Chalmers & Cater, 2005). In SI, interpreters need to manage multiple inputs, such as listening to speech while processing visual cues such as texts, images, gestures, or real-time captions. The way in which they direct their visual attention is crucial to producing accurate high-quality interpretations. Research has shown that visual support can enhance interpreting accuracy. For example, Stachowiak-Szymczak and Korpal (2019) found that interpreters who had access to PowerPoint slides achieved a higher level of numerical accuracy than those without it; similar benefits have been reported by Lambert (2004). However, static visual aids can also introduce challenges: asymmetrical structures in sight translation and slide-supported SI have been shown to pose additional cognitive demands on interpreters’ processing (Su & Li, 2019; Su et al., 2024). Similarly, AST subtitles dynamically adjust around such asymmetries, which may influence the way interpreters engage visually with AST subtitles (see Discussion for details).

With the increase in technology-assisted SI, interpreters now encounter dynamic visual elements such as ASR captions and AST subtitles. This real-time visual–textual information offers continuous support (or possibly no support) for interpreters and introduces a new area of interest for researching in the field of SI. In a pioneering study, Defrancq and Fantinuoli (2021) used video recordings to investigate whether student interpreters engaged with running ASR transcriptions during SI and how this input affected numerical accuracy. Because the gaze shifts captured in the recordings offered only partial evidence, such cases were labelled “presumed ASR use”. That study tested three scenarios: (1) no ASR support; (2) ASR available without observable engagement; and (3) ASR available with observable engagement (e.g., gaze shifts). Numerical accuracy was highest in the third scenario.

Similarly, Yuan and Wang (2023) conducted an eye-tracking study on students’ cognitive processing and interpreting accuracy in technology-assisted SI. Live captions were provided by ASR. They found that the students focused their visual attention on the captioning area when the speaker mentioned numbers and proper names. The level of accuracy in interpreting numbers and proper names improved when ASR captions were available compared to when they were not. Li and Chmiel (2024) examined the ways in which real-time simulated ASR captions affect output accuracy and cognitive load in technology-assisted SI. The professional interpreters in this study worked under five conditions: no captions and captions with 100%, 95%, 90%, and 80% precision. The interpreters paid more attention to the captions than to the speaker. The ASR captions, regardless of their level of precision, improved the accuracy of the interpreting of proper nouns, numbers, and key content words. The theta-based cognitive load was significantly lower with 100% and 80% precise captions than when there were no captions.

Su and Li (2024) expanded on previous research by incorporating AST subtitles alongside ASR captions in their eye-tracking experiment on technology-assisted SI. They found that their cohort of student interpreters actively referred to both ASR captions and AST subtitles to support their interpreting. Renditions of the entire source text and of problematic triggers such as asymmetrical structures were more accurate in technology-assisted SI than in SI without such support. These findings suggest that ASR captions and AST subtitles provide useful visual aids for interpreters during SI.

Whereas previous studies have focused on ASR captions in SI, few have examined both ASR captions and AST subtitles together. This limited research reveals a gap in understanding how professional interpreters process these visual aids. In addition, the relationship between the way visual attention is captured by ASR captions and AST subtitles, on the one hand, and output accuracy, on the other, remains largely unexplored. Moreover, most studies also focus on a single interpreting direction instead of comparing L1–L2 and L2–L1 scenarios. It is still unclear how devoting visual attention to ASR captions and AST subtitles varies between the L1–L2 and the L2–L1 interpreting directions.

Eye tracking makes it possible to analyse the way in which interpreters’ attention is captured by different visual sources such as ASR captions and AST subtitles. Key eye-tracking measures such as total fixation duration (TFD), percentage of fixation duration (PFD), and fixation count per minute (FCmin) provide a multifaceted view of interpreters’ visual attention management during interpreting tasks. The TFD represents the cumulative time that participants fixate on areas of interest and this serves as a direct index of sustained attention and cognitive processing. It indicates how much raw time is allocated to processing specific stimuli. In contrast, the PFD expresses the fixation duration as a percentage of the total duration of fixations. Whereas both TFD and PFD measure fixation duration, the PFD normalizes the data; this enables meaningful comparisons across participants, tasks, or conditions where the overall fixation duration may vary. This relative measure highlights the proportion of total attention devoted to particular areas, in this way contextualizing the absolute duration captured by the TFD. Finally, FCmin measures the frequency of fixations per minute. FCmin reflects the intensity of visual attention during an SI task. A higher FCmin indicates greater visual attention as it suggests more frequent engagement with visual stimuli. By examining both absolute (TFD) and relative (PFD) fixation durations, researchers can understand not only how long attention is sustained but also how it is captured by different elements in relation to the overall task. Measuring the FCmin also reveals the intensity of an interpreter’s visual engagement. Together, these measures offer a more comprehensive picture of the management of attention during interpreting tasks.

In theory, visual attention is influenced by both bottom-up factors and top-down factors (Theeuwes & Failing, 2020). Bottom-up factors are driven by external stimuli or features in the environment, whereas top-down factors are guided by task prioritization, task demands, prior knowledge and experience, and self-regulation, among other factors. We believe that bottom-up and top-down factors can effectively explain how ASR captions and AST subtitles are attended to visually by professional interpreters in the context of technology-assisted SI. Bottom-up factors, such as the dynamic features of captions and subtitles, can influence the interpreter’s visual attention by serving as salient visual signals that attract the interpreter’s gaze. Meanwhile, top-down factors, such as the interpreter’s task priorities and familiarity with the languages involved, can guide the way in which they respond to the textual information presented by ASR captions and AST subtitles. For example, interpreters who prioritize source text comprehension may focus more on ASR captions to support their understanding of the speech. Similarly, their greater familiarity with either the SL or the TL may influence where interpreters focus their visual attention: they may be more drawn to ASR captions or AST subtitles in the language they are more familiar with. Gaining knowledge of this interaction between bottom-up and top-down factors enhances our understanding of the way in which visual attention is managed in technology-assisted SI.

3. Directionality and visual attention in technology-assisted simultaneous interpreting

Professional interpreters often work in both directions, either interpreting from their second language (L2) into their first language (L1) or vice versa. This makes directionality a significant topic in interpreting studies. Previous research has mainly examined the cognitive load involved in L1–L2 and L2–L1 interpreting (e.g., Bartłomiejczyk & Gumul, 2024; Su & Li, 2019). Some studies have taken a more detailed look at the way interpreters process the source text in each direction during sight translation (Su & Li, 2020). The results indicate that interpreters encounter different challenges when interpreting in L1–L2 versus L2–L1. When interpreting from L1 into L2, interpreters may struggle more with TL production, such as finding precise vocabulary or maintaining grammatical accuracy and fluency. In contrast, when interpreting from L2 into L1, the main challenge often lies in SL comprehension, especially when the speech contains unfamiliar accents or complex syntax, or is delivered rapidly (see Lu, 2018; Su et al., 2024). Overall, the findings seem to indicate that L1–L2 interpreting is more cognitively demanding than L2–L1 interpreting. This conclusion is based primarily on objective measures, including interpreting accuracy, the frequency of disfluencies in the output, and eye-tracking data reflecting visual attention and processing effort.

In technology-assisted SI, research has primarily concentrated on the ways interpreters process ASR captions, with comparatively fewer studies exploring the visual processing of AST subtitles. Notably, most of these studies examine only one interpreting direction, either L2–L1 (Defrancq & Fantinuoli, 2021; Li & Chmiel, 2024; Yuan & Wang, 2023) or L1–L2 (Su & Li, 2024). The interaction between visual attention to ASR captions and AST subtitles and interpreting directionality remains largely underexplored. Chen and Kruger (2024) investigated the impact of interpreting direction on visual attention in computer-assisted CI. In phase one, the interpreter listens to the source speech and respeaks it into speech recognition software, generating a transcript that is then machine-translated. In phase two, the interpreter delivers the target speech using both the transcript and its translation as support. Their results revealed that during respeaking, the participants mainly focused on listening and respeaking, with greater speech recognition monitoring correlating with higher respeaking quality. In the production phase, they relied more on the MT text, although increased attention to MT improved the quality only in the L2–L1 direction. Since CI differs cognitively from SI, further research is needed to explore the way directionality affects visual attention to ASR captions and AST subtitles in technology-assisted SI.

In the present study, the ASR captions were expected to support the interpreters’ comprehension processes, whereas the AST subtitles were expected to aid their production. It is important to note that both the ASR captions and the AST subtitles were generated by machines. One way to explore the ways in which interpreters’ visual attention to ASR captions and AST subtitles might differ in the L1–L2 and L2–L1 directions is to examine the relative difficulty of comprehension and production in each direction (Chmiel, 2016). Since comprehension in interpreters’ L2 is relatively more difficult in L2–L1 interpreting and production in interpreters’ L2 tends to be more challenging in L1–L2 interpreting, it is likely that interpreters might view more ASR captions in their L2 during L2–L1 interpreting and more AST subtitles in their L2 during L1–L2 interpreting.

However, interpreters may prefer to read textual information in their L1, whether ASR captions or AST subtitles, regardless of their intended support function. Lee (2024) found that two Japanese conference interpreters had difficulty quickly reading Korean (L2) ASR captions, suggesting that L1 preference may outweigh the intended function of such tools. This points to the importance of studying the ways in which interpreters’ attention is captured by technology in both L1–L2 and L2–L1 interpreting and also the reasons behind these priorities.

With these considerations in mind, the present study aimed to assess the ways in which professional interpreters visually process information during technology-assisted SI in both L1–L2 and L2–L1 directions, using eye-tracking measures. Furthermore, we examined the correlation between interpreters’ visual attention and their interpreting accuracy. Specifically, we gathered empirical evidence to respond to the following three questions:

· How much visual attention is captured by real-time source text captions generated by ASR and real-time target text subtitles generated by AST during technology-assisted SI?

· Does the amount of visual attention captured by the ASR captions or AST subtitles vary with the interpreting direction?

· How is the visual attention captured by the ASR captions or AST subtitles associated with interpreting accuracy in each interpreting direction?

4. Methodology

4.1 Participants

Fourteen professional interpreters (ten women, four men) participated in the study. The interpreters’ mean age was 40 (SD = 4.91) and their mean self-reported interpreting experience was seven years (SD = 2.58). They were native Chinese speakers with English as their L2. All of the participants signed written consent forms prior to the experiment.

4.2 System descriptions

The real-time ASR captions and the AST subtitles used in the study were generated by Tencent Simultaneous Interpreting.[1] According to its official website, the system offers high recognition precision, with the accuracy rate for Mandarin speech reaching 97%. In our study, both the Chinese and the English ASR captions achieved 98% accuracy and the AST subtitles also reached 98% (see section 4.3 for details). Although the official website does not disclose specific latency data, we invited two additional professional interpreters to subjectively evaluate the system’s latency, and their feedback was positive (see also section 4.3).

Tencent Simultaneous Interpreting adopts a strategy that segments the audio stream at preset time intervals. This strategy divides continuous speech into fixed-length frames for transmission and recognition. The system also incorporates a delayed error-correction mechanism to improve the accuracy of the ASR captions. It retains a portion of the preceding context and uses subsequent audio input to confirm and refine earlier recognition results when necessary.

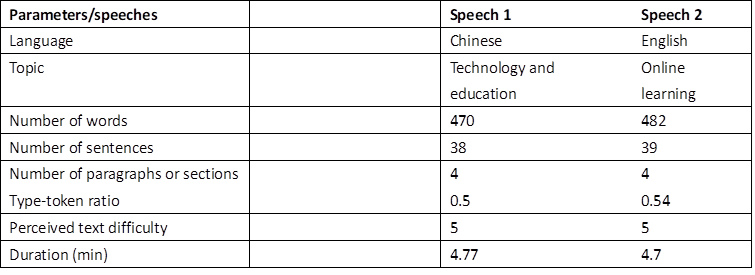

4.3 Materials

The experiment used one Chinese and one English speech, carefully matched by topic, word count, sentence count, paragraph count, type-token ratio, perceived text difficulty, and duration (see Table 1). The type–token ratio was calculated by dividing the number of unique words by the total number of words in each language. Two interpreting studies professors independently rated the text difficulty on a 1–7 scale, with 1 being “very easy” and 7 “very difficult”. They read the texts and were informed that the materials would be used in SI with technological assistance. Both rated the texts as a 5, yielding a mean difficulty rating of 5 for each. The English speech was recorded by a native English speaker and the Chinese speech by a native Mandarin speaker, both in a soundproof room. Each speech had a delivery rate of approximately 100 words per minute and was divided into four sections of comparable length. For Speech 1, the sections contained 116, 116, 117, and 121 words (M = 117.5, SD = 2.06) and for Speech 2, they contained 122, 122, 116, and 122 words (M = 120.5, SD = 2.60).

Table 1

Features of the source speeches

The real-time ASR captions and AST subtitles were dynamically updated as the system processed the ongoing speech. These captions and subtitles served as the two areas of interest (AOIs) and were displayed at the bottom of the screen in white text on a black background (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Screenshot of the display setup with two AOIs (ASR captions, AST subtitles) during L1–L2 (Chinese–English) technology-assisted SI

To ensure consistency across the participants, the ASR captions and the AST subtitles were pre-recorded and played back during the experiment. Both types of text were simultaneously visible on the screen during the task, each displayed in two lines (see also Li & Chmiel, 2024). The number of words per caption or subtitle was limited to fit within two lines. As new words appeared, part of the existing text, typically the first line, was removed to accommodate the incoming content. To simulate a real CI setting closely, we added the PowerPoint slides above the captions and subtitles. The slides were designed to resemble those typically used by speakers in live presentations. Each slide featured a title and four bullet points, arranged in the same order as the corresponding section in the source speech (see also Su et al., 2024).

The language and content on the slides were identical to those of the source speech to ensure congruence between the visual and the auditory input. The source speech offered more detailed contextual information for each bullet point. Because the slide content overlapped with the ASR captions and the AST subtitles, we acknowledge that this may have reduced the participants’ reliance on the captions and subtitles for comprehension or production. However, this design choice was made to simulate authentic conference interpreting settings in which interpreters frequently work with PowerPoint slides. In such contexts, interpreters either actively use ASR captions and/or AST subtitles, or these are provided to them as part of their working environment. Although the simultaneous presentation of multiple visual elements such as slides, captions, and subtitles could theoretically compete for visual attention, we believe that the high degree of congruence between these sources may have mitigated such competition. Nevertheless, we encourage readers to take into account the potential influence of slide inclusion on participants’ visual attention when they interpret the findings of this study.

We calculated the ASR caption accuracy using the NER model (Romero-Fresco & Martínez Pérez, 2015), achieving a mean accuracy of 98% across both interpreting directions. The AST subtitle accuracy was assessed using the NTR model (Romero-Fresco & Pöchhacker, 2017), also reaching 98% mean accuracy in both directions. To evaluate the feasibility of the ASR captions and the AST subtitles further, we conducted a preliminary test with two additional professional interpreters. We gathered their subjective evaluations regarding latency, accuracy, and overall user experience. Each interpreter was asked to interpret one section from Speech 1 and one from Speech 2 with the support of the tools. Their feedback was then collected by means of a brief interview. According to their feedback, the ASR captions and the AST subtitles demonstrated acceptable latency and high accuracy, and provided a positive user experience. However, they noted that the changing wording in the AST subtitles occasionally distracted them.

4.4 Procedure

Each participant was instructed to sit in front of the Tobii Pro Spectrum remote eye-tracker (sampling rate = 600 Hz). The stimuli were displayed on a 23.8-inch LED screen with a resolution of 1 920 × 1 080 pixels, viewed from a distance of 65 cm. Tobii Pro Lab software version 1.171 was used to capture and export both gaze data and oral recordings of the interpreting outcomes for statistical analysis.

Before the experimental session began, each participant completed a five-minute warm-up practice of SI with ASR captions and AST subtitles in both directions, presented in the same format as the experimental materials. After completing the required calibration procedure, the participants performed two technology-assisted SI tasks. The order of the two tasks was counter-balanced to mitigate potential order effects. Half of the interpreters first interpreted Speech 1 from Chinese into English (L1–L2 direction), followed by Speech 2 from English into Chinese (L2–L1 direction). The remaining participants completed the tasks in the reverse order. For both Speech 1 and Speech 2, the interpreters interpreted the content in its original sequential order, from Section 1 through to Section 4. This ordering reflected the natural progression of the speech.

After the experiment, a semi-structured interview was conducted in Chinese, the participants’ native language. Eleven participants reviewed their gaze data with a researcher and discussed their experience with using ASR captions and AST subtitles. Specifically, they were asked to share how they decided where to focus their visual attention between the ASR captions and the AST subtitles. They were also asked whether their attention was captured differently when interpreting into their L1 compared to their L2 and, if so, why. The interviews were recorded using an external recorder and both the interpreting outcomes and the interviews were transcribed verbatim for analysis.

4.5 Data analysis

In our experiment, the mean accuracy of the eye-tracking data (measured in degrees) was 0.12 (SD = 0.07) for L1–L2 technology-assisted SI and 0.13 (SD = 0.06) for L2–L1 technology-assisted SI. These values were significantly lower than the 0.5-degree threshold commonly reported in previous eye-tracking studies, with lower accuracy values indicating greater precision.

In order to analyse the eye-tracking data, we defined two areas of interest (AOIs): the ASR captions and the AST subtitles (see Figure 1). The commonly reported measures of visual attention – including the TFD, the PFD, and the FCmin – were calculated for each AOI (see section 2 for a detailed explanation of each measure).

In addition to these eye-movement measures, an analysis of the interpreting accuracy was also conducted to illustrate the correlation between interpreters’ visual attention to each AOI and their interpreting accuracy. The transcripts of the interpreting outputs were evaluated for information accuracy by two independent interpreting trainers using a holistic text-level approach. Accuracy was assessed based on the proportion of original messages accurately conveyed with due consideration being given to deviations, inaccuracies, and omissions. The ratings followed a rubric-based 4-band scale adapted from Han (2018), ranging from 1 (least accurate) to 8 (most accurate). The inter-rater reliability was high (Krippendorff’s α = 0.97 for L1–L2 interpreting and 0.93 for L2–L1 interpreting). The average of the two raters’ scores was used as the accuracy score for each interpreter when interpreting each section.

We adopted Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-phase thematic analysis approach to analyse the semi-structured interviews. All of the recordings were transcribed and read repeatedly by both authors in order to gain familiarity with the data. Both authors coded four interviews independently, focusing on the way the interpreters’ visual attention was drawn to the ASR captions and/or the AST subtitles, and how this attention pattern varied according to interpreting direction. Coding was conducted systematically across the dataset and relevant segments were collated for each code. Intercoder reliability, as measured by percentage agreement, was 75%. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved through consultation of the data, after which the first author coded the remaining interviews. The first author grouped the codes into preliminary themes, which were cross-checked by the second author. Final themes were defined and named, and key comments were selected to illustrate how and why interpreters attended to the ASR captions or the AST subtitles, with particular attention being given to differences across the interpreting directions. Both authors contributed to this phase to ensure that the themes accurately reflected the data and that the selected comments were both relevant and representative.

To examine the impact of ASR captions and AST subtitles on interpreters’ visual attention (Research Question 1) and the interaction of visual attention with interpreting direction (Research Question 2), we constructed three linear mixed-effects models using the lme4 package (Bates et al., 2015) in R 4.4.2. Satterthwaite approximations were applied to calculate the p-values. In all three models, the independent variables were AOI (ASR vs AST), interpreting direction (L1–L2 vs L2–L1), and their interaction. The dependent variables were the TFD in the first model, the PFD in the second, and the FCmin in the third. The TFD was log-transformed so that the residuals were approximately normally distributed.

To explore the relationship between the interpreters’ visual attention to the ASR captions and the AST subtitles and their interpreting accuracy in each direction (Research Question 3), we applied a series of linear mixed-effects models. The independent variables in each model were the TFD, the PFD, and the FCmin on either the ASR captions or the AST subtitles. The dependent variable in all the models was accuracy scores. Separate analyses were conducted for the L1–L2 and the L2–L1 interpreting directions as our research question centres on the manner in which visual attention to the ASR captions or the AST subtitles relates to interpreting accuracy in each direction. Since we were not specifically investigating the main effect of directionality on accuracy, nor its potential to modulate the relationship between visual attention and accuracy, we opted for separate models to keep the analysis aligned with our primary focus. We used backward elimination to select random effects structures, starting with maximal models justified by the design (Bates et al., 2018). This process yielded random-intercept-only models, each including random effects for participants (interpreters) and items (each section of each speech in the technology-assisted SI task).

5. Results

5.1 Visual attention captured by ASR captions and AST subtitles

The first research question examined the extent to which professional interpreters’ visual attention was captured by the ASR captions and the AST subtitles. The inferential tests for the main effect of AOI (ASR captions, AST subtitles) and its interaction with interpreting direction on visual attention are reported together in section 5.2.

Overall, the ASR captions received a mean TFD of 98.09 seconds, whereas the AST subtitles received a mean TFD of 39.14 seconds. The average PFD was 38.52% for the ASR captions and 15.51% for the AST subtitles. In addition, the ASR captions and the AST subtitles had a mean FCmin of 67.59 and 31.33, respectively. The remaining time was either spent fixating on other areas of the screen, such as the PowerPoint slides, or involved moments when the participants were looking away from the screen.

5.2 Directionality effect on visual attention captured by ASR captions and AST subtitles

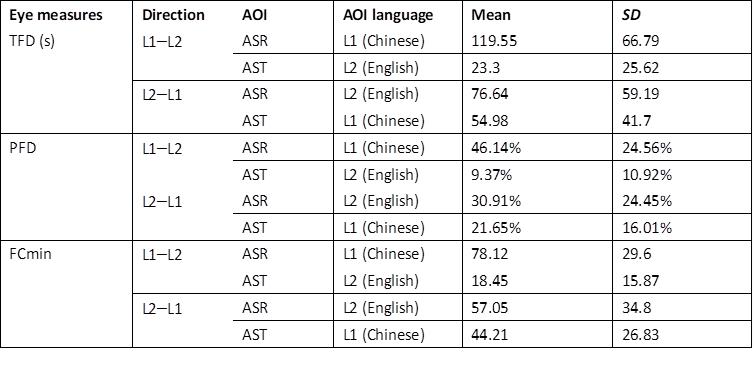

The second research question examined the effect of directionality on visual attention as captured by ASR captions and AST subtitles. The TFD, PFD and FCmin were calculated and tabulated in each direction (see Table 2).

Table 2

Descriptive data for eye-movement measures in ASR captions and AST subtitles with respect to the L1–L2 and the L2–L1 directions

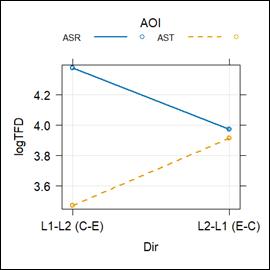

An LMER analysis of the TFD revealed a significant interaction

effect between AOI and interpreting direction (β = 0.85, t =

6.56, p < 0.001). In the L1–L2 SI, the ASR captions

attracted longer total fixation durations than the AST subtitles (β = 0.90,

t = 9.81, p < 0.001), whereas no

significant difference was observed between the two AOIs in the L2–L1

direction. The fixations were longer on the ASR captions than on the AST

subtitles in the L1–L2 direction, but not in the L2–L1 direction. In addition, the

ASR captions in the L1 during L1–L2 interpreting received more total fixation

time than the ASR captions in the L2 during L2–L1 interpreting (β = 0.40,

t = 4.41, p < 0.001). In contrast, the AST

subtitles in the L1 during L2–L1 interpreting attracted more fixation time than

the AST subtitles in the L2 during L1–L2 interpreting (β = 0.44,

t = 4.86, p < 0.001). The captions and

subtitles presented in the interpreter’s L1 received longer total fixation

durations.

An LMER analysis of the TFD revealed a significant interaction

effect between AOI and interpreting direction (β = 0.85, t =

6.56, p < 0.001). In the L1–L2 SI, the ASR captions

attracted longer total fixation durations than the AST subtitles (β = 0.90,

t = 9.81, p < 0.001), whereas no

significant difference was observed between the two AOIs in the L2–L1

direction. The fixations were longer on the ASR captions than on the AST

subtitles in the L1–L2 direction, but not in the L2–L1 direction. In addition, the

ASR captions in the L1 during L1–L2 interpreting received more total fixation

time than the ASR captions in the L2 during L2–L1 interpreting (β = 0.40,

t = 4.41, p < 0.001). In contrast, the AST

subtitles in the L1 during L2–L1 interpreting attracted more fixation time than

the AST subtitles in the L2 during L1–L2 interpreting (β = 0.44,

t = 4.86, p < 0.001). The captions and

subtitles presented in the interpreter’s L1 received longer total fixation

durations.

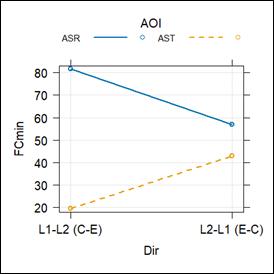

Figure 2

Interaction effects between AOI and direction on logTFD

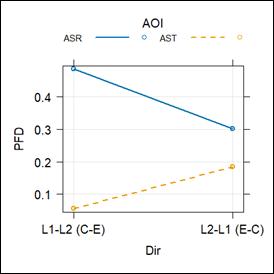

An LMER analysis of the PFD revealed a significant interaction effect between AOI and interpreting direction (β = 0.31, t = 6.08, p < 0.001). The ASR captions received a higher PFD than the AST subtitles, with a greater effect in the L1–L2 direction (β = 0.43, t = 11.48, p < 0.001) compared to the L2–L1 direction (β = 0.12, t = 3.32, p = 0.001). The PFD on the ASR captions was higher than on the AST subtitles and this difference was more pronounced during L1–L2 interpreting than during L2–L1 interpreting. Furthermore, the ASR captions in the L1 during L1–L2 interpreting had a higher PFD than those in the L2 during L2–L1 interpreting (β = 0.18, t = 5.21, p < 0.001). In contrast, the AST subtitles in the L1 during L2–L1 interpreting received a higher PFD than those in the L2 during L1–L2 interpreting (β = 0.13, t = 3.46, p < 0.001). Again, the captions and subtitles presented in the interpreter’s L1 received a higher percentage of fixation durations.

Figure 3

Interaction effects between AOI and direction on PFD

An LMER analysis of the FCmin revealed a significant interaction effect between AOI and direction (β = 48.13, t = 5.42, p < 0.001). The ASR captions had a higher FCmin than the AST subtitles in the L1–L2 direction (β = 62.25, t = 9.85, p < 0.001) and also received a higher FCmin in the L2–L1 direction (β = 14.12, t = 2.27, p = 0.025), though the difference was greater in the L1–L2 direction. The FCmin on the ASR captions was higher than that on the AST subtitles, and this difference was more pronounced during L1–L2 interpreting than during L2–L1 interpreting. In addition, the ASR captions in the L1 during L1–L2 interpreting had a higher FCmin compared to those in the L2 during L2–L1 interpreting (β = 24.56, t = 3.92, p < 0.001). In contrast, the AST subtitles in the L1 during L2–L1 interpreting received a higher FCmin than those in the L2 during L1–L2 interpreting (β = 23.57, t = 3.75, p < 0.001). Again, the captions and subtitles presented in the interpreter’s L1 received a higher fixation count per minute.

Figure 4

Interaction effects between AOI and direction on FCmin

5.3 Association between visual attention and interpreting accuracy

The third research question examined the association between the professional interpreter’s visual attention and their interpreting accuracy. The interpreting accuracy was rated on a scale of 1–8 (8 = the highest quality); the mean value was 7.4 and 7.31 for the L1–L2 and the L2–L1 direction, respectively.

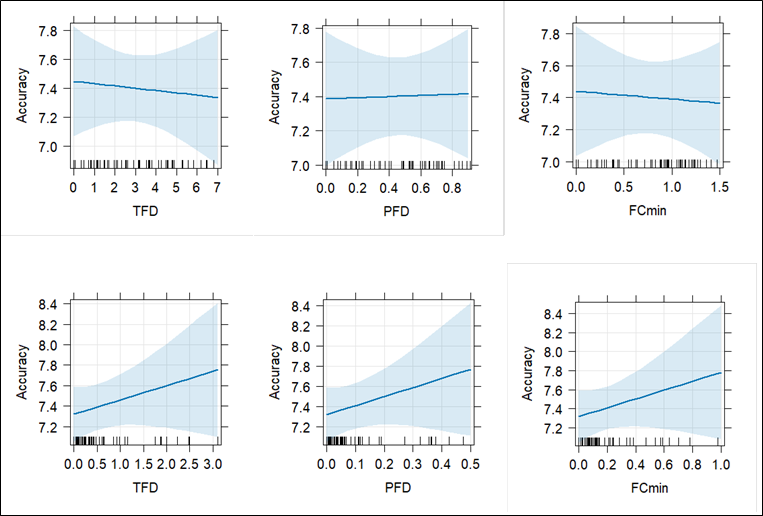

In the L1–L2 direction, the LMER analysis revealed no significant association between the TFD on the ASR captions and accuracy (β = –0.02, t = –0.31, p = 0.76). Similarly, neither the PFD on the ASR captions (β = 0.03, t = 0.09, p = 0.93) nor the FCmin on the ASR captions (β = –0.05, t = –0.23, p = 0.82) showed a significant relationship with accuracy. Furthermore, the TFD, PFD or FCmin on the AST subtitles did not predict a score of accuracy (TFD: β = 0.14, t = 1.15, p = 0.26; PFD: β = 0.9, t = 1.19, p = 0.24; FCmin: β = 0.47, t = 1.14, p = 0.26).

Figure 5

Associations between TFD, PFD, and

FCmin on ASR captions (upper row) and AST subtitles (lower row) with accuracy

in the L1–L2 direction (TFD and FCmin were rescaled)

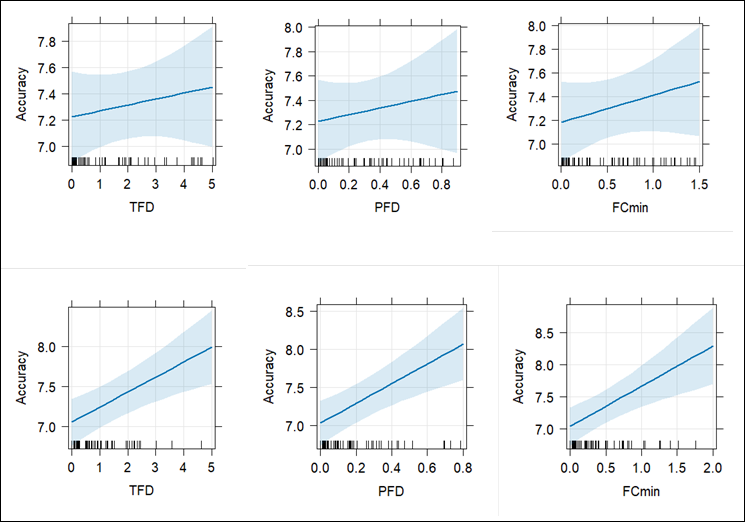

In the L2–L1 direction, neither the TFD, the PFD nor the FCmin on the ASR captions predicted the score of accuracy (TFD: β = 0.05, t = 0.73, p = 0.47; PFD: β = 0.27, t = 0.73, p = 0.47; FCmin: β = 0.23, t = 1.09, p = 0.28). Nevertheless, the TFD on the AST subtitles was associated with accuracy (β = 0.19, t = 3.58, p < 0.001), which meant that there was a tendency for the interpreting to be more accurate when professional interpreters devoted longer total fixation durations on the AST subtitles in their L1. Similarly, both the PFD and the FCmin on the AST subtitles in the interpreters’ L1 in the L2–L1 direction significantly predicted interpreting accuracy (PFD: β = 1.29, t = 3.78, p < 0.001; FCmin: β = 0.63, t = 3.64, p < 0.001).

Figure 6

Associations between TFD, PFD, and FCmin on ASR captions (upper row) and AST subtitles (lower row) with accuracy in the L2–L1 direction (TFD and FCmin were rescaled)

5.4 Interview findings on visual attention

The previous sections reported on the eye-tracking data. In this section, we present the interview data in order to triangulate the findings. Four key themes emerged from the analysis.

First, the ASR captions captured more visual attention than the AST subtitles. Two interpreters reported focusing more on the ASR captions, regardless of the interpreting direction. They used the ASR captions as a primary aid for comprehension during SI. As one interpreter noted: “Most of the time I relied on the ASR captions to help me, and sometimes I could do a bit of sight translation from them.”

Second, the AST subtitles attracted more visual attention than the ASR captions. One interpreter reported that they focused primarily on the AST subtitles, regardless of the interpreting direction.

Third, the Chinese ASR captions and AST subtitles captured more attention than the English versions. Five interpreters reported that their attention was more frequently drawn to the Chinese text in both ASR and AST. They expressed a clear preference for reading content in Chinese. As one interpreter said, “if I only have a very short amount of time [to process information], I will choose to read the Chinese text first.” Fourth, the English ASR captions and AST subtitles captured more attention than the Chinese versions. One interpreter reported focusing more on the English text across both the ASR captions and the AST subtitles.

6. Discussion

6.1 ASR captions generally attracted more attention than AST subtitles

Overall, the results indicate that, during technology-assisted SI, ASR captions generally draw more attention than AST subtitles, especially from L1 to L2. This section first explains why the ASR captions generally attracted more attention than the AST subtitles, followed by a discussion in section 6.2 on why this effect was particularly pronounced in the L1–L2 direction.

One possible reason for the difference in overall visual attention between the ASR captions and the AST subtitles could be the features of the captions and the subtitles themselves. In this study, the speeches used as the source text were spoken clearly and recorded with high sound quality. As a result, the ASR captions accurately captured the speakers’ words and flowed smoothly, with only approximately 5.8 occurrences of alterations per 100 source-text words across both Chinese and English. These ASR captions provided interpreters with a reliable and consistent representation of the source speech.

In the present study, the AST subtitles were generated using a cascading approach (see Fantinuoli, 2023). First, ASR converts the spoken SL into the written text. Then, the machine translates the written text from the SL into the TL. Each stage relies on the output of the previous one, creating a “cascade” of processes that together produce the real-time AST subtitles. Consequently, the accuracy and stability of the AST subtitles were expected to align closely with those of the ASR captions. However, while the ASR captions remained relatively stable, the AST subtitles exhibited some changes. These changes in the AST subtitles were not primarily caused by variations in the ASR captions but they seemed instead to result from the need to maintain low latency and the specific linguistic characteristics of the language pair involved (see also Lu, 2023).

To maintain low latency and provide the interpreters with translated texts ahead of their own delivery, the AST subtitles appeared rapidly and adapted dynamically as the source speech progressed. Notably, because the source speech progresses linearly, once an ASR segment is finalized for display, it remains largely stable. In contrast, the AST subtitles continued updating themselves when new information from the source text affects the translation.

Another factor contributing to these changes in the AST subtitles was language-pair specificity (Gile, 2009). A typical example of this is the asymmetrical structures between Chinese and English: Chinese often employs head-final or left-branching structures, whereas English typically uses head-initial or right-branching structures. These structural asymmetries can complicate the stability of real-time AST subtitles.

For instance, in the L1–L2 direction, the speaker said a head-final structure in Chinese: “已在网上学习了基础知识的学生” (with the head “学生” [students] in bold; a word-for-word translation would be “have online learned the basic knowledge students”). The corresponding English translation is: “students who have learned basic knowledge online” (with the head “students” in bold). The ASR captions recognized the words accurately and smoothly within this structure. However, the AST subtitles initially displayed “have learned the basic” before eventually correcting themselves into “students who have learned the basic knowledge online”.

In this example, we analysed the synchronized recordings of the speaker’s speech, the scanpaths, and the oral renditions. We found that most of the interpreters relied on listening comprehension and the ASR captions to construct their interpreting output, correctly using "students" as the subject. Some interpreters also consulted the PPT slides in combination with listening and the ASR captions.

Another example is found in the L2–L1 direction. The speaker said an English sentence with a head-initial structure: “I was not pleased with the scene that looked like the Olympic Games in a classroom” (head: the scene). The corresponding Chinese translation could be “我不喜欢教室里看起来像奥运会的场面” (head: 场面 [the scene]). In this case, the ASR captions accurately and fluently captured the speaker’s original sentence. However, the initial AST subtitles displayed an incomplete version: “我对这一幕并不满意” (“I am not pleased with the scene”), before correcting themselves to “我对教室里看起来像奥运会的场面很不满意” (“I was not pleased with the scene that looked like the Olympic Games in a classroom”).

Synchronized replay revealed two main patterns. First, some interpreters initially said “我对这一幕并不满意” (“I am not pleased with the scene”) and then elaborated by adding “因为教室里看起来像奥运会一样” (“because the classroom looked like the Olympic Games”), mainly relying on listening comprehension combined with the ASR captions or the AST subtitles. Others restructured the sentence by first describing the classroom scene, saying “好像在教室举行奥运会一样” (“It looked like the Olympic Games were taking place in the classroom”), followed by expressing their evaluation: “我对此不满意” (“I was not pleased with this”). They mainly relied on listening comprehension and ASR captions, or a combination of listening comprehension, AST subtitles, and PPT slides.

This adaptability of the AST subtitles was beneficial to enhancing the interpreting accuracy. It provided the interpreters with partial information early on to reduce waiting time and later revisions conveyed the complete meaning necessary for accurate production. Nevertheless, it also introduced a level of variability and unpredictability, which might affect the way AST subtitles capture interpreters’ visual attention. The variability of AST subtitles may lead professional interpreters to rely more on ASR captions due to their greater consistency. This tendency was probably due to the challenge interpreters experienced in tracking the changing information presented by the AST subtitles. As one interpreter noted: “Sometimes the AST subtitles adjust the word order … and I have to revise my own output accordingly.” Similarly, Defrancq and Fantinuoli (2021) reported that interpreters were distracted by the changing shapes of numbers in the running transcriptions. However, it is important to note that their study focused solely on ASR transcriptions and did not include AST subtitles.

More importantly, top-down cognitive factors, such as the self-perceived priority of SI, may also explain how professional interpreters directed visual attention. In the interviews, the professional interpreters consistently emphasized that their primary focus in SI, whether in the L1–L2 or the L2–L1 direction, was always on comprehending the source text. As one interpreter noted: “Comprehension is the most important thing [during SI]; I think this has become the standard pattern for professional interpreters.” This emphasis led them to prioritize ASR captions that offered a clear and uninterrupted understanding of the SL content. Similarly, Bartłomiejczyk (2006) highlighted the crucial role of comprehension in SI, noting that, if comprehension failed, the entire interpreting process was at risk. The ASR captions, which almost faithfully transcribed the speaker’s words, underpinned this priority.

The observed low percentage of fixation duration and low fixation count per minute on the AST subtitles in technology-assisted SI differ from Chen and Kruger’s (2024) findings in technology-assisted CI, where the dwell time on machine-translated text reached 64.44% (L1–L2) and 48.17% (L2–L1). This difference could be attributed to the distinctive features of SI and CI.

In technology-assisted SI, interpreters simultaneously listen, read ASR captions and AST subtitles, and produce output, which requires a careful distribution of processing resources across these tasks. In this study, the professional interpreters strategically relied more on the ASR captions than on the AST subtitles. In contrast, in technology-assisted CI, comprehension (listening and reading ASR captions) and reformulation occur sequentially. During the reformulation phase, interpreters do not have to share processing capacity between comprehension and production under high cognitive load, as would be necessary in SI (Gile, 2009). Therefore, in Chen and Kruger’s (2024) study, the interpreters relied more on machine-translated text than on ASR captions to support target-speech production.

Also, it is important to note that the differing results may be attributed to the respective characteristics of MTs in technology-assisted SI and CI. In technology-assisted SI, the source speech unfolds live and both ASR captions and AST subtitles are generated and updated in real-time. In contrast, in technology-assisted CI, the MTs are produced by an MT system and presented all at once.

6.2 ASR captions attracted more attention than AST subtitles, with the attention gap more pronounced in the L1–L2 direction

Interpreting direction influenced visual attention, with a larger attention gap occurring between ASR captions and AST subtitles in the L1–L2 direction. This greater ASR–AST attention gap in the L1–L2 direction may be explained by the interpreters’ stronger preference for reading the source text in Chinese when it appears in their native language. In the L2–L1 direction, although the ASR captions still attracted more attention than the AST subtitles, the preference for reading the English source text weakened. In contrast, the translated Chinese subtitles became more attractive and narrowed the attention gap between ASR and AST.

The eye-tracking results were supported by the interview data: five interpreters reported being more frequently drawn to the Chinese text in both the ASR captions and the AST subtitles. The results suggest that the professional interpreters tended to look at the ASR captions and the AST subtitles in their L1 (Chinese) during technology-assisted SI. The interpreters’ native language and the task demands of SI may constitute two key top-down factors which account for the influence of interpreting direction on these visual-attention patterns.

Being native Chinese speakers, the professional interpreters naturally found it more efficient to engage with Chinese text. As one interpreter explained: “Because Chinese is my native language, I can understand it faster.” Another interpreter noted: “Since Chinese is my native language, I can read faster, access information more quickly, and make decisions more rapidly.” As a result, they displayed greater engagement with the ASR captions and the AST subtitles in their L1 compared to those in their L2. These results corroborated those of Lee (2024), who found that professional interpreters experienced difficulty in reading the ASR captions quickly in their foreign language during SI.

This finding suggests that professional interpreters tend to leverage their linguistic proficiency to facilitate comprehension and production. In addition, SI is cognitively demanding and can lead to cognitive saturation (Gile, 2009). Chinese characters, being box-shaped, appear to be denser than English words, which consist of sequences of letters (Yu & Reichle, 2017). Furthermore, the linguistic information conveyed in Chinese is more compact (Rayner, 2009). These features may help interpreters to process information more efficiently under pressure. This probably accounts for their greater focus on Chinese captions and subtitles, which are in their native language (L1).

Our findings differed from those of Chen and Kruger (2024). In their study on technology-assisted CI, student interpreters showed greater reliance on ASR captions when those captions were in their L2 than when they were in their L1 during the production phase. Similarly, they relied more on MTs in their L2 than in their L1, as indicated by higher dwell-time percentages. As discussed in section 6.1, unlike in SI, CI allows interpreters to devote more attention to texts in a less familiar language during reformulation.

6.3 Paying more attention to AST subtitles in L1 in the L2–L1 direction led to more accurate interpreting output

Although the professional interpreters focused more on the ASR captions, this approach did not lead to improved interpreting accuracy. Interestingly, positive correlations were observed between interpreting accuracy and the total fixation duration, the percentage of fixation duration, and the fixation count per minute on the AST subtitles in the interpreters’ L1 in the L2–L1 direction. However, this was not the case in the L1–L2 direction. It is difficult to pin down the reasons for such findings. However, we suspect that one possible contributing top-down cognitive factor is the self-evaluation motive of professional interpreters (see Heidemeier & Staudinger, 2012). In the interviews, one interpreter mentioned comparing what was heard in their L2 with the corresponding AST subtitles in their L1 to evaluate and confirm the understanding of the source text. This self-evaluation process was perceived to support accurate interpreting. Further research is needed to gain a better understanding the self-evaluation motive of professional interpreters during technology-assisted SI.

Our interpretation is also in line with previous research suggesting that L2 comprehension can be cognitively demanding for unbalanced bilinguals during SI from L2 (English) into L1 (Chinese) (e.g., Lu, 2018, 2021). It also echoes the findings of Lu et al. (2019), who reported that professional interpreters regarded foreign-language listening and reading comprehension as essential and central components of simultaneous interpreter competence.

In addition, the observed relationship between the visual attention captured by AST subtitles in L1 during L2–L1 interpreting and interpreting accuracy may be influenced by the dynamic nature of the AST subtitles. Therefore, future research with more refined designs is needed to help us understand these findings better.

7. Implications

The current study has important implications for interpreting, particularly in the context of technology-assisted SI.

First, the study reveals a correlation between an increased focus on AST subtitles during L2-to-L1 SI and improved accuracy. Whereas ASR captions typically attract more attention, interpreters can enhance their accuracy by strategically directing their focus to AST subtitles when needed. This implies that interpreters could benefit from training that enables them to shift their focus flexibly between ASR captions and AST subtitles based on the interpreting direction. Encouraging interpreters to monitor and manage real-time AST subtitles actively in their L1 could be particularly beneficial as it allows them to leverage the strengths of both ASR captions and AST subtitles to improve the accuracy of their interpreting output.

Second, the study underscores the importance of enhancing interpreters’ reading and comprehension skills in their L2. This is crucial to using both real-time ASR captions and AST subtitles effectively. Interpreters who possess strong language-processing skills in their L2 will be better equipped to process the information presented in captions and subtitles quickly and accurately, which could possibly support more accurate performance in SI.

Together, these findings advocate a comprehensive approach to interpreter training and practices that emphasize both cognitive flexibility and language-processing skills. This approach is essential to enabling interpreters to use technological tools such as ASR captions and AST subtitles effectively. By incorporating these tools into their practice, interpreters are better able enhance their accuracy in real-time interpreting scenarios. This comprehensive approach not only improves their accuracy but also ensures that interpreters remain adaptable and effective in an increasingly technology-assisted field.

8. Summary and conclusion

This study explored the ways in which professional interpreters’ attention is captured during SI with real-time ASR captions and AST subtitles. It specifically examined whether attention patterns varied across interpreting directions and how these patterns related to interpreting accuracy.

The findings indicate that interpreters focused more on ASR captions than AST subtitles, particularly in the L1–L2 direction. This inclination, along with a tendency to prioritize both captions and subtitles in their native language (L1), was probably driven by an interaction of bottom-up factors, such as caption and subtitle features, and top-down cognitive factors, including the interpreters’ self-perceived priority of SI, their native language, and task demands. In addition, a positive correlation was observed between interpreting accuracy and visual attention to AST subtitles in interpreters’ L1 during the L2–L1 direction.

Overall, these insights collectively enhance our understanding of the way professional interpreters interact with technology in real-time contexts. This study offers practical implications for improving the processing of real-time captions and subtitles in SI. In addition, one intriguing area for future research is to explore the way AST subtitles evolve over time and to develop strategies that help interpreters adapt effectively to these changes.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the National Social Science Fund of China (grant number: 24CYY094).

References

Bartłomiejczyk, M. (2006). Strategies of simultaneous interpreting and directionality. Interpreting, 8(2), 149–174. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.8.2.03bar

Bartłomiejczyk, M., & Gumul, E. (2024). Disfluencies and directionality in simultaneous interpreting: A corpus study comparing into-B and into-A interpretations from the European Parliament. Translation & Interpreting, 16(1), 38–54. https://doi.org/10.12807/ti.116201.2024.a03

Bates, D., Kliegl, R., Vasishth, S., & Baayen, R. H. (2018). Parsimonious mixed models. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1506.04967

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. M., & Walker, S. C. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Chalmers, A., & Cater, K. (2005). Exploiting human visual perception in visualization. In C. D. Hansen & C. R. Johnson (Eds.), Visualization handbook (pp. 807–816). Elsevier Butterworth–Heinemann. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012387582-2/50043-5

Chen, S., & Kruger, J.-L. (2024). Visual processing during computer-assisted consecutive interpreting: Evidence from eye movements. Interpreting, 26(2), 231–252. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.00104.che

Chmiel, A. (2016). Directionality and context effects in word translation tasks performed by conference interpreters. Poznań Studies in Contemporary Linguistics, 52(2), 269–295. https://doi.org/10.1515/psicl-2016-0010

Defrancq, B., & Fantinuoli, C. (2021). Automatic speech recognition in the booth: Assessment of system performance, interpreters’ performances and interactions in the context of numbers. Target, 33(1), 73–102. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.19166.def

Fantinuoli, C. (2022). Conference interpreting and new technologies. In M. Albl-Mikasa & E. Tiselius (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of conference interpreting (pp. 508–522). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429297878-44

Fantinuoli, C. (2023). Towards AI-enhanced computer-assisted interpreting. In G. Corpas Pastor & B. Defrancq (Eds.), Interpreting technologies: Current and future trends (pp. 46–71). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/ivitra.37.03fan

Gile, D. (2009). Basic concepts and models for interpreter and translator training (Rev. ed.). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.8

Han, C. (2018). Latent trait modelling of rater accuracy in formative peer assessment of English–Chinese consecutive interpreting. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(6), 979–994. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1424799

Heidemeier, H., & Staudinger, U. M. (2012). Self-evaluation processes in life satisfaction: Uncovering measurement non-equivalence and age-related differences. Social Indicators Research, 105(1), 39–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9762-9

Lambert, S. (2004). Shared attention during sight translation, sight interpretation and simultaneous interpretation. Meta, 49(2), 294–306. https://doi.org/10.7202/009352ar

Lee, J. (2024). Exploring the possibility of using speech-to-text transcription as a tool for interpreting. In R. Moratto & H.-O. Lim (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of Korean interpreting (pp. 387–412). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003349723-30

Li, T., & Chmiel, A. (2024). Automatic subtitles increase accuracy and decrease cognitive load in simultaneous interpreting. Interpreting, 26(2), 253–281. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.00111.li

Lu, X. (2018). Propositional information loss in English-to-Chinese simultaneous conference interpreting: A corpus-based study. Babel, 64(5–6), 792–818. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.00070.lu

Lu, X. (2021). A study on the causes and mechanisms of propositional information loss in English-Chinese simultaneous interpreting. Chinese Translators Journal, 42(3), 157–167.

Lu, X. (2022). Comparing the quality and processes of Chinese–English simultaneous interpreting by interpreters and a machine. Foreign Language Teaching and Research, 54(4), 600–610, 641. https://doi.org/10.19923/j.cnki.fltr.2022.04.011

Lu, X. (2023). Human and machine simultaneous interpreting: Cognitive processes, competence, quality and future trends. Chinese Translators Journal, 44(3), 135–141.

Lu, X., Li, D., & Li, L. (2019). An investigation of layers of components and subcompetences of professional simultaneous interpreter competence. Foreign Language Teaching and Research, 51(5), 760–773, 801.

Pöchhacker, F. (2024). Is machine interpreting interpreting? Translation Spaces. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.23028.poc

Rayner, K. (2009). The 35th Sir Frederick Bartlett Lecture: Eye movements and attention in reading, scene perception, and visual search. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 62(8), 1457–1506. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470210902816461

Romero-Fresco, P., & Martínez Pérez, J. (2015). Accuracy rate in live subtitling: The NER model. In R. Baños Piñero & J. Díaz Cintas (Eds.), Audiovisual translation in a global context: Mapping an ever-changing landscape (pp. 28–50). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137552891_3

Romero-Fresco, P., & Pöchhacker, F. (2017). Quality assessment in interlingual live subtitling: The NTR Model. Linguistica Antverpiensia, New Series – Themes in Translation Studies, 16, 149–167. https://doi.org/10.52034/lanstts.v16i0.438

Stachowiak-Szymczak, K., & Korpal, P. (2019). Interpreting accuracy and visual processing of numbers in professional and student interpreters: An eye-tracking study. Across Languages and Cultures, 20(2), 235–251. https://doi.org/10.1556/084.2019.20.2.5

Su, W., & Li, D. (2019). Identifying translation problems in English-Chinese sight translation: An eye-tracking experiment. Translation and Interpreting Studies, 14(1), 110–134. https://doi.org/10.1075/tis.00033.su

Su, W., & Li, D. (2020). Exploring processing patterns of Chinese–English sight translation. Babel, 66(6), 999–1024. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.00192.su

Su, W., & Li, D. (2024). Cognitive load and interpretation quality of technology-assisted simultaneous interpreting. Foreign Language Teaching and Research, 56(1), 125–135, 161. https://doi.org/10.19923/j.cnki.fltr.2024.01.012

Su, W., Li, D., & Ning, J. (2024). Syntactic asymmetry and spillover effects in simultaneous interpreting with slides: An eye-tracking study on beginner interpreters. Perspectives. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676x.2024.2427680

Theeuwes, J., & Failing, M. (2020). Attentional selection: Top-down, bottom-up and history-based biases. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108891288

Yu, L., & Reichle, E. D. (2017). Chinese versus English: Insights on cognition during reading. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 21(10), 721–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2017.06.004

Yuan, L., & Wang, B. (2023). Cognitive processing of the extra visual layer of live captioning in simultaneous interpreting. Triangulation of eye-tracked process and performance data. Ampersand, 11, Article 100131, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amper.2023.100131