Exploring the translation–development interactions from an emergent semiotic perspective: A case study of the Greater Bay Area, China

Xi Chen

Macau University of Science and Technology

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8057-4623

Abstract

The Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area (Greater Bay Area or GBA), a megalopolis in China, has developed rapidly and achieved remarkable results in recent years. This study aims to explore the translation–development interactions in the GBA from an emergent semiotic perspective. Following the studies on translation and development (Marais, 2014, 2018; Olivier de Sarden, 2005), this study views development as a semiotic process of making meaning under specific affordances and constraints, while translations could be regarded as meaningful intercultural mediations or adaptations that help to transcend language barriers and support regional development. Through exploring different translation practices in education, economics and the media, this study analyses how translation plays a mediating role in the development of the GBA in multiple respects. It first examines the adaptation of curriculum designs of translation courses in the universities of the GBA and then analyses the functions of the translation industry in support of the economic development of the GBA. Finally, it analyses the translations of international publicity material on the tourism websites of the GBA to explore the ways in which translation mediates in the cultural exchanges and coordinated developments regarding the GBA and its component parts. The research findings show that translation practices interact with the developmental contexts at the linguistic, economic and cultural levels, contributing to the coordinated development of the GBA.

Keywords: emergent semiotics; social–cultural emergence; development; translation; Greater Bay Area (GBA)

1. Introduction

The Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area (referred to as Greater Bay Area or GBA), is a megalopolis in China that includes nine cities in Guangdong Province and two Special Administrative Regions, Hong Kong and Macao. In 2017, the governments of Guangdong, Hong Kong and Macao signed a framework agreement to set the goals and principles of cooperation, which marked the establishment of key cooperation areas in the GBA. In 2019, the Outline Development Plan for the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area was issued, signifying a new stage in the development of the GBA. This outline proposed a series of basic principles and areas of development, emphasizing innovation, reformation, coordinated development and ecological conservation. It was expected that by 2022 the framework of a world-class urban cluster would be formed in the GBA and that by 2035, with high-level connections and diverse cultural exchanges, an international first-class bay area would be fully completed that would enable much-improved living, working and travel arrangements.

With a population of approximately 5 per cent of China’s total population and a GDP equivalent to 12 per cent of the total GDP of the Chinese mainland, the GBA is the largest and richest economic region in China and also ranks as the 12th largest economy in the world (Woetzel et al., 2019). With the highest concentration of Fortune 500 companies in China, the GBA houses many Chinese technology companies, such as Huawei, ZTE and Tencent, and is regarded as an emerging Silicon Valley of Asia owing to its development potential in the field of high-tech innovation (Bork, 2019). Apart from economic cooperation, the GBA also has great potential for developing education and culture. There are more than 200 universities and colleges in the GBA, including world-class universities and leading academic centres which produce a large number of highly educated graduates every year (Wang et al., 2019). Moreover, as an important hub of the Belt and Road Initiative1 (Liu, 2019), the GBA offers fertile soil for cultural convergence and communication between Guangdong Province, Hong Kong and Macao in which the Cantonese culture and Western cultures create new possibilities for integration.

During the past four years, the GBA has developed rapidly and has achieved remarkable results in various respects: technological innovation, financial services, education, transportation, tourism, etc. The rapid development of such a huge megalopolis that attracts attention globally is worth investigating. Scholars have conducted various studies on the GBA from different perspectives, including technology innovation (Lin & Zheng, 2020), economic development (Yu, 2019; Zhou & Zhang, 2020), tourism and hospitality (Lu et al., 2020; Luo & Lam, 2020), environmental protection and sustainable development (Chang, 2020), education (Wang et al., 2019), and history and culture (Li, 2020). However, compared to these other areas, there have been few studies which have explored language usage in the GBA (Qu, 2021), with even fewer studying the field of translation and development. In recent years, the thriving development of the language industry has contributed greatly to cultural exchange and coordinated development in the GBA, a contribution that has great potential for further exploration.

This study aims to explore the translation–development interactions in the GBA from the perspective of emergent semiotics. Following other studies on translation and development (Marais, 2014, 2018; Olivier de Sardan, 2005), this study views development as a semiotic process of making meaning under specific affordances and constraints in which the meanings include thoughts, emotions, actions and phenomena in a society or a culture. Meanwhile, translations could be viewed as meaningful intercultural mediations or adaptations that transcend language barriers in developing countries and regions. From this perspective, translation and development are meaning-making processes that interact with each other. Specific constraints in development contexts might affect translation practices and products, whereas translation could also work as an agent or method to influence social and cultural phenomena in the development contexts.

Through considering different instances of translation practices in education, economics and the media in the GBA, this study analyses the way translation plays a mediating role in the development of the GBA in a number of respects. First, it examines the adaptations to the curriculum designs of translation courses at the universities of the GBA to investigate mediation in respect of language needs and language competence. Secondly, it analyses the functions of the translation industry in the economic development of the GBA, with a focus on the specific translation industry in Macao. Thirdly, it analyses the translation of international publicity material on the tourism websites of the GBA to explore the ways in which translation mediates in the cultural exchanges and coordinated development between the cities of the GBA. Through the analyses of the translation–development nexus at the linguistic, economic and cultural levels, this study attempts to explore the mediating roles of translation in the social and cultural realities of the GBA, which is a neglected research field both in translation studies and in development studies in China.

2. Translation and development

Having made continual progress during the past 70 years, development studies is currently undergoing three transitions: the transition from programme-centred, technique-centred or engineer-centred thinking to human-centred thinking; that from a focus on technical transfer to dialogic interaction; and that towards a post-development imagination (Marais, 2019b). First, the human-centred approach to development studies (Coetzee et al., 2001; Desai & Potter, 2014) examines the complex interrelations between material welfare and human welfare. Scholars of the ‘human capabilities approach’ (Nussbaum, 2011; Nussbaum & Sen, 1993) argue that development should provide people with the opportunities to realize their potential, bringing human beings into the centre of the development debate. Secondly, the dialogic approach to development studies (Owen & Westoby, 2012; Westoby & Dowling, 2013) shifts the research focus from macro-economic and political issues to micro-dialogic interactions, delving as it does into the role of dialogue in building a developmental process between individuals in community practice settings. Thirdly, the post-development approach to development studies (Kaplan, 2002; Nederveen Pieterse, 2009, 2010) views the emergence of societies on their own terms, exploring alternative systems of meaning related to development. Nederveen Pieterse (2010) views development as “the organized invention in collective affairs according to a standard of improvement” (p. 3) and suggests that semiotics could assume an important place in development studies.

Among these various development studies, the field of translation and development has so far been relatively under-researched. The relationship between translation and development was first suggested by Olivier de Sardan’s (2005) notion of development in a hermeneutic approach. Olivier de Sardan (2005) regards development as a meaning-making response to environmental constraints and an adaption to social change, which relates the concept of semiosis to the interpretation of meaning-making systems in the development process. Translation therefore involves bringing “two distinct ways of dissecting or perceiving reality” (2005, p. 171) into a relationship with each other, which has more in common with semiology than with linguistics. In addition, Lotman (1990, 2005) conceptualizes development from a biosemiotics perspective and proposes the concept of a semiosphere, which contributes to a greater understanding of translation and development. He views a semiosphere as the “semiotics space necessary for the existence and functioning of languages” (Lotman, 1990, p. 123), which has “a prior existence and is in constant interaction with languages” (Lotman, 1990, p. 123). In this regard, all cultural and social phenomena are created through the semiotic actions of translating an object or an interpretant into another object or interpretant (Marais, 2019b). Moreover, Marais (2013, 2014, 2018, 2019a) has made a series of contributions to the field of translation and development in recent years, greatly promoting the developments of this interdisciplinary research field. In his monographs, Marais (2014, 2019a) systematically arranges with the relevant theories of translation studies, semiotics and development studies, proposing a theoretical framework for investigating development as the emergence of societies through real and complex semiotic responses. His emergent semiotics approach serves as a starting point for the possibility of examining translation phenomena from a non-textual perspective.

In the past five years, further studies have been conducted in the field of translation and development from diverse perspectives. The special issue of The Translator entitled Translation and Development (2018) expands the conceptualization and possibilities of this interdisciplinary research field, including a variety of translation practices in development contexts. For example, Todorova (2018) investigates the contributions of actor-network theory to development and translation studies, examining the interactions between different participants in the process of translating civil-society ideas and discourses. In the translation of civil-society terminology, smaller organizations play an ‘intermediary’ role between the big development donors and the local civil-society sectors; these intermediaries are actively engaged in the process of translating ideas for the public. Chibamba (2018) investigates the translation of public-health campaigns from a sociological perspective with an emphasis on the socio-economic and cultural contexts in which translations take place in a developing country. Adopting a semiotic approach to development studies, Marais and Delgado Luchner (2018) analyse the local and global affordances and constraints of translation and interpreting phenomena in the development contexts of Africa. According to this perspective, translation practices are meaningful adaptations to a specific set of contextual constraints for developing countries to transcend language barriers or manage complex multilingualism (Marais & Delgado Luchner, 2018). Troqe and Pema (2018) also employ a semiotic perspective in development studies, but their discussions are mainly based on Lotman’s framework of the semiosphere, which helps to expand the understanding of translation into “an intersemiotic activity occurring between semiotic parts of different semiospheres and creating or preventing paths of development” (Troqe & Pema, 2018, p. 339). These diverse studies help to incorporate concepts from translation studies and development studies, further promoting the theoretical and empirical studies in this interdisciplinary domain. In addition, translation practices in international NGOs (Delgado Luchner, 2018; Footitt, 2017) have also been investigated in this field, which discusses language mediation practices, intercultural relations and politico-social power dynamics in transnational institutions in development contexts.

Compared to the promising progress in the West, few studies touch on the topic of translation and development in China. Proposing the concept of translation economics, Xu (2014) analysed the relationship between translation and the economy and explores the possible model of translation economic management. His study notes the important role of translation in economic development, but it lacks an in-depth theoretical exploration of the interactions between translation and development. Apart from this, the development of the translation industry is also an area of great research interest and activity in China: research areas include an economic perspective of the translation industry (Si & Guo, 2016; Si & Yao, 2014), education and training for the translation industry (Liu, 2018; Yu, 2015) and the impact of the translation industry on regional economic development (Ding & Li 2011; Zhao, 2017). However, these studies focus mainly on the contribution of the translation industry to economic development, without any theoretical conceptualization of translation–development interactions or detailed case studies of different translation practices in development settings in China. The present research in this domain lacks an in-depth investigation of the involvement of translation in the social and cultural realities of China; for this reason, such a research gap is the starting point of this study.

3. Translating social–cultural emergence: a perspective of emergent semiotics

With an ever-growing flood of multimodal ensembles in the multimedia era, translation studies embrace more possibilities, and new approaches expand our understanding of translation concepts and practices. The semiotic concept in translation studies originates from Jakobson’s (1959/1966) notion of intersemiotic translation, which refers to “an interpretation of verbal signs by means of signs of nonverbal sign systems” (p. 233). Toury (1986) broadens the definition of translating to “a series of operations whereby one semiotic entity is transformed into, and replaced by, another entity, pertaining to another [sub-]code or semiotic system” (p. 1128). Apart from these interpretations, in Peircean semiotics, a sign is “a triadic relationship between a representamen (or sign-vehicle), an object (for which the representamen stands) and an interpretant (the meaning of the representamen)” (Marais, 2018, p. 102); the process through which meanings or interpretants are created is called translation. In this regard, semiosis is “a process driven by translational activities” and “all semiotic processes are equally translational” (Marais, 2019a, p. 52), so we can claim that all social and cultural phenomena have a translatory aspect to them to some extent.

Semiotics not only expands our understanding of translation studies but also provides conceptual tools to contain both the material and the ideal in development studies. The concept of semiotics can be interpreted from different perspectives in development studies. In this study, the theoretical framework for analysis and discussion is mainly the emergent semiotic response theory proposed by Marais (2014, 2017, 2018); for this reason, my investigation of translation–development interactions is conducted from the perspective of emergent semiotics. Marais’s emergent semiotic approach helps to conceptualize the relationship between translation and development in social and cultural realities. He agrees with Olivier de Sardan’s (2005) view that development is an adaptation to social change, a mediated process and a matter of cultural borrowing. He therefore regards translation as comprising “complex adaptive systems in which both individual agents and social structure are conceptualized as non-linear factors” (Marais, 2014, p. 135) in the development of social reality. From this emergent semiotic perspective, this study views development as a semiotic response under certain constraints by the particular space, time and semiotic attractors in development contexts. Therefore, the development in the GBA is viewed as a semiotic process of making meaning under particular affordances and constraints in which the meanings may include thoughts, emotions, actions and phenomena in a society or a culture. Meanwhile, translation practices in the GBA could be viewed as meaningful intercultural mediations or adaptations whose purpose is to transcend language barriers for the sake of regional development.

Moreover, Marais (2014) argues that translation is a complex phenomenon which emerges from a number of semiotic subsystems. He employs the term “semiotic translation” as “a particular semiotic phenomenon emerging from a substratum of phenomena in cases in which one has an interaction between semiotic systems or subsystems” (p. 106). The social reality includes many subsystems, with more sub-subsystems in each subsystem. For example, language is one semiotic subsystem of the social reality; in the subsystem of language there are different sub-subsystems such as phonetics, syntax, pragmatics and discourse. Therefore, semiotic translation is “an inter-ness semiotic phenomenon” (p. 17) that examines inter-systemic semiotic relationships in the emergence of social reality.

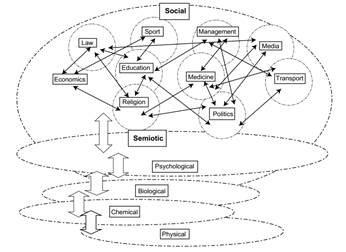

Marais (2014) also demonstrates the role of translation in the emergence of social reality (see Figure 1), which provides a theoretical basis that helps us understand the role of translation practices in the development contexts of the GBA.

Figure 1

The role of translation in the emergence of social reality (Marais, 2014, p. 108)

Here emergence is a concept employed to “think about systems without reducing them to any of their constituent parts” (Marais, 2014, p. 47) and it is a way of explaining the development of different levels of reality. As shown in Figure 1, the semiotic system is one of the inter-phenomena in reality; it constitutes the boundary between the psychological and the social. Translation is “a phenomenon in which semiotic inter-systemic relationships among social systems or subsystems obtain” (Marais, 2014, p. 107). Therefore, different forms of social reality – the economy, education, politics, the media and culture – emerge from the semiotic interactions between human beings; meanwhile, translation participates in the emergence of these different forms of social reality. When participating in the emergence of culture, semiotic translation shows features of social reality in culture; when participating in the emergence of economics, it shows features of social reality in economics. This emergent semiotic approach not only provides a theoretical framework with which to conceptualize translation studies across culture, time, space and ideology, but also creates a philosophical space in which to interpret the role of translation in the emergence of social reality.

Marais’s framework of translating social–cultural emergence lays a theoretical foundation for the case analysis in this study. The development in the GBA is regarded as a semiotic process of making meaning under particular affordances and constraints in development contexts; translation in the GBA is in turn viewed as a complex phenomenon emerging from various semiotic systems and subsystems in the social reality. Different translation practices in the GBA deal with different inter-systemic semiotic relationships which function as meaningful intercultural mediations in or adaptations of the regional development of the GBA. The case analysis of translation–development interactions examines materials from situations where translation practices occur in the development context of the GBA, including official documents, academic reports and website materials used in education, economics and the media in the GBA. Through documentary analysis, this research attempts to explore the way translation is involved in the different social and cultural realities of the GBA in a development context.

4. Translation–development interactions in the Greater Bay Area

This section contains detailed case analyses of translation–development interactions in the GBA from the perspective of emergent semiotics. It focuses on the involvement of translation in the three representative forms of social and cultural reality in the GBA: education, economics and the media.

4.1 Interactions in education: translation training and regional development

The Outline Development Plan for the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area2 proposes five kinds of strategic positioning of the GBA: (1) a dynamic world-class urban cluster; (2) an international science and technology innovation centre with global influence; (3) important support for the Belt and Road Initiative; (4) a demonstration zone for in-depth cooperation between the mainland, Hong Kong and Macao; (5) a high-quality living circle suitable for living, working and travel.

To achieve these goals, language plays an important role in the regional communications and economic exchanges in the GBA. Many spoken languages are used here, such as Mandarin, Cantonese, English, Portuguese, Hakka dialect and Minnan dialect, while four written languages are used, including simplified Chinese characters, traditional Chinese characters, English and Portuguese. Multilingual usage leads to special language requirements in the development of the GBA and, in turn, it promotes the development of related language industries. Translation training therefore also needs to adjust to the regional development of the GBA.

Translation training has been well developed in the GBA, with different undergraduate and postgraduate programmes being offered in translation and interpreting. In Guangdong Province there are 12 universities that offer the programme for Master of Translation and Interpreting (MTI),3 which is an applied postgraduate programme with extensive training in translation practice. In Hong Kong, eight universities offer postgraduate translation programmes, including programmes in Translation, Interpreting, Computer-aided Translation and Bilingual Communication. The MA Translation programmes in Hong Kong are mainly practice-oriented, whereas the MPhil programmes pay more attention to Translation Studies. In Macao, the University of Macau provides a postgraduate programme in Translation Studies, a balanced programme that gives equal weight to academic research and practical training. The Macao Polytechnic Institute offers undergraduate and postgraduate programmes in Chinese–English and Chinese–Portuguese Translation and Interpreting to cater for the specific language needs in Macao.

These translation programmes at different levels have trained a large number of translation talents for the development of the GBA. In addition, some universities have adjusted the curriculum designs of their translation programmes, tailoring them to the requirements of regional development in the GBA. For example, as the leading foreign language university in the GBA, the Guangdong University of Foreign Studies (GDUFS) has pioneered the adjustment of curriculum design towards regional development. Since 2020, the GDUFS School of Interpreting and Translation Studies has set up a new course titled ‘Workshop of Core Industries in the Greater Bay Area’4 for the MTI students, which is an innovative practical course that includes a series of professional workshops on three core aspects of the GBA: political diplomacy, finance and technology. The course description highlights the aim of this workshop as being to meet the need to build high-end language services in the GBA. It has been devised in cooperation with various international and domestic resources – such as the United Nations, national ministries and commissions, embassies and consulates in Guangzhou and Fortune 500 enterprises – to cooperate in developing curricula in political diplomacy, finance, Internet usage, biotechnology, etc. Following a different approach from traditional translation training, all the workshop courses are jointly taught by senior experts from core industries in the GBA, professional interpreters, and teachers from the Interpreting Education and Research Center of GDUFS. Such a practice-oriented teaching mode is geared to meeting the needs of regional economic development in the GBA.

The ‘Workshop of Core Industries in the Greater Bay Area’ is a good example to demonstrate the interactions between translation training and regional development. The curriculum design of the workshop is more practice-oriented and is closely aligned to the development of core industries in the GBA, which could be regarded as an adaptation to the affordances and constraints of regional development in the GBA. For instance, in 2021, the ‘Workshop of Core Industries in the Greater Bay Area’ organized a series of practical courses on political diplomacy, finance and technology. In the workshop on political diplomacy, senior interpreters from the United Nations, China’s Ministry of Commerce and the Hong Kong Legislative Council provided lectures and interpreting training as appropriate to different political and diplomatic occasions. In the government departments in Hong Kong, such as the Legislative Council, the interpreting tasks include not only Chinese–English interpreting but also Mandarin–Cantonese interpreting. In this way, the multilingual capacity of interpreting students is emphasized to meet the need for multilingual language services in the GBA. In the workshop on finance, the financial interpreters of Ping An Bank gave lectures and practical training in professional interpreting in financial enterprises. In the workshop on technology, through off-campus practical training, the interpreting experts of Huawei introduced the quality management model for interpreting of Huawei. As a Chinese multinational technology company headquartered in the GBA, Huawei has its own interpreting mode aligned with overseas business development and media public relations. Such a workshop helps MTI students to learn about the way professional interpreting works in a technology company and it serves to improve their integrative competence with a view to future employment in the GBA.

Through this series of workshops, students are given opportunities to learn more about the translation requirements of industries in the GBA and receive professional translation and interpreting training that meet the requirements of regional development in the GBA. Currently, the available professional translators and interpreters cannot meet the increase in language needs generated by the rapid development of the GBA, so the translation training mode needs to be mediated to produce more foreign-language translation (and interpreting) talents with multiple competences. These talents should not only have recognized translation and interpreting qualifications and abilities but should also have professional knowledge of other fields such as politics, finance and technology so that they are competent enough to perform various kinds of translation and interpreting work required in the GBA.

In addition, in recent years, GDUFS has set up a series of compulsory and elective courses on translation and localization for the MTI programme: machine translation (MT) and post-editing, language service project management, website localization, software localization, technical communication and technical writing. These courses on translation and localization are also adaptations in line with the language-mediation needs in the development contexts of the GBA, which highlight the training of translators in competences in the areas of information technology and MT. According to the 2020 Chinese Language Service Industry Development Report,5 information technology accounts for 55.6 per cent of the fields requiring translation services, ranking as the Number One translation service provided by the language-service enterprises in China. In the context of the Information Age, information technology and artificial intelligence (AI) have been booming in the Pearl River Delta, while language intelligence and language technology are widely used in the language-service industry. The integration of language technology and translation training contributes to the cultivation of language-intelligent technical personnel, which will promote the vigorous development of the language-service industry in the GBA.

Through such translation–development interactions, the deep engagement with regional affordances results in the improvement of translation training programmes; meanwhile, the improved curricular designs of translation training are evidence of an adjustment to the language needs of regional development in the GBA. However, some constraints might also affect the translation–development interactions in the GBA. As the abovementioned courses are provided for MTI students in GDUFS, the translation training courses tailored to regional development in the GBA seem to constitute an elitist programme aimed at those who already have good bilingual communication capacities in Chinese and English. In 2021, 406 students were admitted into the MTI programmes of seven universities in the GBA, among whom 170 MTI students were admitted by GDUFS.6

The limited scale of professional translation training will have a limited influence on regional development in the GBA and therefore may not have the desired positive affect on the large industrial scale of the development. Therefore, more adaptations of the translation training in the GBA should be a necessary forerunner of designing large-scale training courses at different levels, such as some short-term translation courses on the development of the language industry or the application of translation technology in the GBA. Such translation courses should not be confined to undergraduate and postgraduate students who major in translation and interpreting. On the contrary, the courses should be open to translation and interpreting practitioners in the different enterprises and public institutions of the GBA in order to enhance the translation–development interactions in education in the GBA further.

4.2 Interactions in economics: translation industry and economic value

Language industries create economic value for the regional development of the GBA, including disciplines such as language assessment, language training, language translation, language exhibition and language technology. Among these different types of language industry, the translation industry has developed rapidly in recent years. For example, in Zhuhai, an important city of the GBA, the number of translation enterprises has accounted for 42.9 per cent of the total number of language enterprises in the city (Li & He, 2020).

In addition, Macao is a core city with special translation practices and a specialized translation industry in the GBA. Macao had been a colony of Portugal since 1775 and was handed over to China in 1999. In 2002, the Macao Special Administrative Region (SAR) liberalized the gaming industry and permitted the entry of transnational capital and global entertainment companies. Now a famous international tourist city, Macao is among the best leisure destinations in the world. Its unique historical features and geographic location influence multilingual usage in Macao: the official languages of Macao SAR are Chinese and Portuguese, while English is also widely used, especially in business, tourism and education. The affordances and constraints of this multilingual development context generate particular translation practices and account for the vibrancy of the translation industry in Macao.

Among the four core cities in the GBA, Macao is positioned as the world tourism and leisure centre, the business services cooperation platform between China and Portuguese-speaking countries, and the exchange and cooperation base for Chinese culture and diversified cultures in the world.7 As a significant hub of the Belt and Road initiative, Macao functions as a bridge of communication between China and Portuguese-speaking countries and between China and the ASEAN countries, so the translation industry in Macao not only includes translation services between Chinese and English but, more importantly, between Chinese and Portuguese. In 2003, the Forum for Economic and Trade Cooperation between China and Portuguese-speaking Countries (Macao) (also known as the Forum Macao) was founded and since then five Ministerial Conferences of the Forum Macao have been held in Macao with great success. At present, Macao is actively promoting the construction of an RMB clearing centre for Portuguese-speaking countries to develop Macao into an RMB offshore financial centre. Meanwhile, the ‘Three Centres’ have been constructed in Macao to facilitate the development of the GBA. These include the Commercial Service Centre for Small and Medium Enterprises of China and Portuguese-speaking Countries, the Distribution Centre for Food Products of Portuguese-speaking Countries and the Convention and Exhibition Centre for Economic and Commercial Cooperation between China and Portuguese-speaking Countries. The economic and trade cooperation strengthens the important status of Portuguese in the economic development of the GBA and also expands the demand for translation services between Chinese and Portuguese. In 2019, the total imports and exports between China and Portuguese-speaking countries reached US$149.6 billion (Qin & Li, 2020), while the conference and exhibition industry in Macao has contributed substantially to the economic development of the service trade. In 2019, 1,524 conferences and exhibitions were held in Macao and it ranked among the top 50 international conference cities in the world.8 The thriving development of the conference and exhibition industry in Macao promotes international trade, investment and tourism; in the mean time, such economic development is inseparable from the support of the related service industry and translation industry.

To repeat Marais’s (2014) perspective, development is an adaptation to social change and translation includes complex adaptive systems involving different factors in the development of social reality. Development contexts in the GBA generate specific constraints for translation practices and the translation industry, while translation functions as an agent that influences the social realities in the development context of the GBA. For instance, the increasing demand for translation services in Macao has promoted the development of MT. In 2017, the Macao Polytechnic Institute (MPI), in cooperation with Global Tone Communication Technology Co., Ltd. and GDUFS, established a Chinese–Portuguese–English Machine Translation Laboratory, contributing in this way to the development of the MT industry in Macao. Later, the Machine-Aided Translation System of Chinese–Portuguese/Portuguese–Chinese Official Documents was launched by this same laboratory. This machine-aided translation system has been used extensively by government departments, banks and industrial organizations in Macao and also in ‘the Belt and Road’ Portuguese-speaking countries. In November 2021, the Chinese–Portuguese Simultaneous Interpretation Machine Translation System 2.0 was launched, which is a leading system of Chinese–Portuguese speech recognition and simultaneous interpretation designed specifically for developing the GBA. This updated system has enhanced the practical functions and the human–machine interactions in translation to help develop Big Data, AI and the Internet of Things in the GBA and the Guangdong-Macao In-depth Cooperation Zone in Hengqin. This cooperation zone will promote language industry cooperation in the GBA in different ways, such as the translation industry, the language training industry and the language technology industry, to build a regional chain of language industries in the GBA that will be integrated into national economic development.

4.3 Interactions in media: cultural exchange and coordinated development

As part of the construction of the GBA, building a cultural bay area is one of the goals of the regional development. The area includes historical and cultural heritage protection, the improvement of public cultural services, and exchanges and cooperation between the youth of the GBA. Owing to special historical factors, multilingual usage has influenced the development of diversified cultures in the GBA, including the British, Portuguese, Guangzhou, Hakka and Minnan cultures. In the development context of the GBA, the differences in the administrative system, ideology and culture of the cities in the GBA may well become constraints on in-depth coordinated development in the future. Coordinated development means that the cities in the GBA maintain complementary relationships between functions and resources. The cooperation between the components of the cultural industry and the reinforcement of cultural exchanges between different cities should not only promote economic development but also enhance cultural identity generally in the GBA. The cultural bay area is built on the regional culture of the GBA: the Lingnan (or Cantonese) culture. With a long history and profound cultural accumulation, Lingnan culture develops in the open and diversified marine cultural background and provides the driving force for the sustainable development of the GBA.

Lingnan culture embodies the essence of the Guangzhou, Hakka and Minnan cultures and it consists of a variety of cultural resources which possess unique Lingnan characteristics – arcaded street architecture, Cantonese morning tea, Cantonese opera, Guangdong embroidery, and lion dancing. As a link to the joint cultural force of the GBA, Lingnan culture helps to promote cultural exchanges and to realize the cultural confidence and identity of the GBA.

On the one hand, to achieve the coordinated development of the culture of the GBA, great effort has been put into protecting the historical and cultural heritage of Lingnan culture through various cultural exhibitions and performance activities. For example, through the joint efforts of the governments of Guangdong Province, Hong Kong and Macao, Cantonese opera was included in the list of World Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2009. To promote the Cantonese opera culture, a series of cultural activities are presented on “Cantonese Opera Day” in Hong Kong and Macao every year.

On the other hand, the construction and development of regional cultural projects have been strengthened in the GBA. These include the Hong Kong Palace Museum and the West Kowloon Cultural District in Hong Kong, the Lingnan cultural centre in Guangzhou and the cultural exchange centre between China and Portuguese-speaking countries in Macao. In 2020, the Culture and Tourism Development Plan for the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area was promulgated, accelerating the development of the GBA into a cultural exchange hub between the East and the West.

In these different types of cultural exchange activity, translation practices in the media play a significant role in the cross-cultural communications of the GBA. For instance, the official tourism websites function as platforms on which to launch international publicity materials, which renders them important platforms for promoting tourism and culture in the GBA. For instance, among the 11 cities of the GBA, 31 per cent of the official tourism websites include an English translation, whereas 34 per cent of the official tourism websites provide two or more translated versions (Qu, 2021). However, except for Hong Kong, Macao and Guangzhou, the majority of the official tourism websites in the cities of the GBA lack multilingual translation services, which may restrict their cultural exchanges and cooperation within and beyond the GBA. Apart from English translations, there are only five official tourism websites in the GBA that offer Korean, Japanese and Thai translations (Qu, 2021), revealing a limited consideration of the coordinated development of tourism markets with neighbouring countries. The constraints of translation practices on these international publicity websites might influence the effective role of translation as intercultural mediation for the regional development of the GBA.

In addition, to promote the exchange and sharing of public cultural resources, the Cultural Information Website of Guangdong, Hong Kong and Macao9 has been established; it provides resourceful cultural information on the cooperation in libraries, museums, performance activities, intangible cultural heritage protection, and cultural and creative industries in the GBA. By integrating diverse cultural resources among the cities in the GBA, this website contributes to the coordinated development of culture in this area. However, it is regrettable that this website does not provide translated versions, because without them translation is denied the opportunity to play a mediating role in the coordinated development of culture in this important medium.

It is regrettable that, while most of the official tourism websites in the GBA focus on introducing tourism and the cultural resources of one specific city or tourist attraction, they do not publicize the integrated tourism resources of the GBA as a whole. Yet it is noteworthy that the website of the Hong Kong Tourism Board contains a special section on the GBA10 which integrates the tourism resources and information of all 11 of the cities in the GBA. Here there are translated versions of the tourism materials in 11 different languages in one section of the website. The English version is further divided into several varieties of English that are found in English-speaking countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zealand – which indicates the consideration shown to speakers of English in all its varieties by the international language services in Hong Kong. In this special section, the multilingual tourism and cultural publicity includes a transportation guide, the historical and cultural backgrounds of scenic sites and the culinary treasures to be found in the GBA. Translation therefore becomes a positive adaptation to the coordinated development of the GBA, which provides potential tourists from diverse countries with an opportunity to learn about the unique and diverse cultures in the different cities of the GBA.

The translation practices of the international publicity materials are intercultural mediations to the affordances and constraints of regional development in the GBA. The integration of cultural information in the GBA through the media contributes to cultural exchange and cooperation, which helps to realize cultural identity, promote policy interactions and, finally, to facilitate coordinated development in the GBA. On some occasions, the regional cultural similarities may lead to similar industrial development in a region and result in unnecessary competition in regional economic development, which may increase the difficulty of enabling coordinated development. Therefore, the cities in the GBA should take full advantage of their special resources and different positioning to enable or enhance complementary collaboration and the coordinated development of culture. For instance, Hong Kong and Macao could be viewed as the cultural integration centre in the GBA where Western cultures and Lingnan culture integrate to promote regional development; Macao and Zhuhai are positioned as the tourism and leisure centres for cultural export in the GBA; with its rich technological innovation resources, Shenzhen could serve as the base for developing cultural innovation industries in the GBA.

5. Conclusion

In this study, the emergent semiotic approach provides an opportunity to reconsider the relationship between translation and development. Development in the GBA is viewed as a meaning-making process subject to particular affordances and constraints; translation in the GBA is a complex phenomenon that emerges from various social and cultural realities. It plays the role of enabling meaningful intercultural mediations or adaptations for regional development. Through analyses of the different translation practices in education, economics and the media, this study investigates the mediation of translation in the development of the GBA. The research findings show that translation practices interact with the developmental contexts in the linguistic, economic and cultural spheres, contributing to the coordinated development of the GBA.

Regarding translation practices in education, the adaptations of curriculum designs of university translation courses contribute to the cultivation of foreign language talents with multiple competences and language-intelligent technical personnel, which demonstrates the mediation of translation training in the development of the language service industry in the GBA. Regarding translation practices and their relation to the economy, the positioning of Macao as the business service cooperation platform between China and Portuguese-speaking countries has led to a special translation industry and its economic value in Macao. The development contexts of the GBA have given rise to substantial translation practices between Chinese and Portuguese in the conference and exhibition industry in Macao. The growing demand for translation services in Macao has also facilitated the flourishing development of MT between Chinese and Portuguese in recent years.

Regrading translation practices in the media, the translation of international publicity materials has served to accelerate cultural exchange and the realization of cultural identity, in turn enhancing the coordinated development of the GBA.

These translation practices in different social and cultural realities have played a positive mediating role in the regional development of the GBA in the linguistic, economic and cultural spheres. Meanwhile, certain contextual constraints also affect the in-depth translation–development interactions and generate some problems in the translation industries in the GBA. First, the language industries in the cities of the GBA mainly develop spontaneously, so sometimes similar industrial development may result in competition between the cities in the GBA and therefore have a negative impact on the attempts at coordinated development. Therefore, the cities in the GBA should make full use of their special resources and develop specific translation industries according to their different positioning in the GBA. For example, with their strong scientific and technological basis, Guangzhou and Shenzhen could develop translation technology and translation training. In addition, through their policy support for the cultural and creative industries, Zhuhai and Macao could focus on developing translation practices for conferences, exhibitions and creative cultural activities.

Secondly, the huge language needs alongside the economic, social and cultural development of the GBA are a major challenge to future development. In the cultural exchange and economic cooperation with domestic regions and foreign countries, the language services in the GBA involve about 200 languages (including dialects), which requires strong language service capabilities and intelligent technology for language services (Li & He, 2020). For instance, in public places such as airports, railway stations, hospitals and scenic sites, some language-intelligent service robots could be used to offer voice guides and translation services. Professional translation training on the application of translation technology is also necessary for the staff in government departments, public institutions and company management in the GBA to improve their translation competence. It is hoped that the emergent semiotic perspective in this study could deepen a collective understanding of the dynamic translation–development interactions in the GBA and enrich translation and development studies in the Chinese context.

Notes

1 The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a global infrastructure development strategy by the Chinese government launched in 2013 to invest in different countries and international organizations. The BRI consists of the Silk Road Economic Belt and the Twenty-first Century Maritime Silk Road; the starting point for the latter is the GBA.

2 https://www.bayarea.gov.hk/en/outline/plan.html

3 https://cnti.gdufs.edu.cn/info/1017/1955.htm

4 The information about the MTI programme curriculum is not available on the website of GDUFS, but I interviewed some teachers of the MTI courses in GDUFS to collect information on this workshop. Some workshop information is also found on the WeChat official account of Interpreting Education and Research Centre (IERC) of the GDUFS School of Interpreting and Translation Studies https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/5Z5yxLuA6pByiw_WlMKbEQ or GDUFS Huangpu Institute https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/r1tbXc0peI7Dyr4dt6Pfog

5 http://www.locatran.com/Index/casedetail/pid/157/id/5920.html

6 I have investigated the enrolment of MTI students in the seven universities in the GBA on the university websites and obtained these statistics.

7 https://www.gce.gov.mo/bayarea/main.aspx?l=cn

8 http://www.xinhuanet.com/gangao/2020-05/25/c_1126031968.htm

9 https://prdculture.org/prdculture/sdwhzx/list.shtml

10 https://www.discoverhongkong.com/eng/greater-bay-area.html

Funding

This work is supported by the FRG Project (FRG-21-005-UIC) of Macau University of Science and Technology.

References

Bork, H. (2019). China’s government plan for its own Silicon Valley. Think: Act Magazine. https://www.rolandberger.com/en/Insights/Publications/Chin’'s-government-plan-for-its-own-Silicon-Valley.html

Chang, X. Y. (2020). 活力粤港澳大湾区之生态环保 [Dynamic Greater Bay Area: Ecological environmental protection]. Guangdong Science and Technology Press.

Chibamba, M. (2018). Translation and communication for development: The case of a health campaign in Zambia. The Translator, 24(4), 301–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2019.1586069

Coetzee, J. K., Graaff, J., Hendricks, F., & Wood, G. (2001). Development: Theory, policy and practice. Oxford University Press.

Delgado Luchner, C. (2018). Contact zones of the aid chain: The multilingual practices of two Swiss development NGOs. Translation Spaces, 7(1), 44–64. https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.00003.del

Desai, V., & Potter, R. B. (Eds.). (2014). The companion to development studies (3rd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203528983

Ding, Z. G., & Li, C. Y. (2011). 略论翻译产业对区域经济发展的影响 [The impact of translation and interpreting industry on regional economic development]. Science and Technology, 1, 56–60.

Footitt, H. (2017). International aid and development: Hearing multilingualism, learning from intercultural encounters in the history of OxfamGB. Language and Intercultural Communication, 17(4), 518–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2017.1368207

Jakobson, R. (1959). On linguistic aspects of translation. In R. A. Brower (Ed.), 1996, On translation (pp. 232–239). Oxford University Press.

Kaplan, A. (2002). Development practitioners and social process: Artists of the invisible. Pluto Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt18fs52f

Li, W. L. (2020). 活力粤港澳大湾区之历史文化 [Dynamic Greater Bay Area: History and culture]. Guangdong Science and Technology Press.

Li, Y., & He, H. Z. (2020, April 11). 语言产业助力粤港澳大湾区建设 [The language industry contributes to the development of the Greater Bay Area]. Guang Ming Daily. https://epaper.gmw.cn/gmrb/html/2020-04/11/nw.D110000gmrb_20200411_2-12.htm

Lin, X. X., & Zheng, X. J. (2020). 活力粤港澳大湾区之科技创新 [Dynamic Greater Bay Area: Scientific and technological innovation]. Guangdong Science and Technology Press.

Liu, K. (2019). China’s Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area: A primer. The Copenhagen Journal of Asian Studies, 37(1), 36–56. https://doi.org/10.22439/cjas.v37i1.5905

Liu, X. J. (2018). 经济全球化环境下翻译产业复合型人才的培养 [The cultivation of interdisciplinary talents in translation industry under the economic globalization environment]. Economic Research Guide, 5, 145–146.

Lotman, Y. (1990). Universe of the mind: A semiotic theory of culture. Indiana University Press.

Lotman, J. (2005). On the semiosphere. Sign Systems Studies, 33(1), 205–229. https://doi.org/10.12697/SSS.2005.33.1.09

Lu, J. K., Liu, S. H., & Luo, F. M. (2020). 粤港澳大湾区会展旅游酒店发展报告 [Report on the development of exhibition, tourism and hotel in Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area]. Social Sciences Academic Press.

Luo, J. M., & Lam, C. F. (2020). City integration and tourism development in the Greater Bay Area, China. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429290725

Marais, K. (2013). Exploring a conceptual space for studying translation and development. Southern African Language and Applied Language Studies, 31(3), 403–414. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073614.2013.864439

Marais, K. (2014). Translation theory and development studies: A complexity theory approach. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203768280

Marais, K. (2017). We have never been un(der)developed: Translation and the biosemiotics foundation of being. In K. Marais & I. Feinauer (Eds.), Translation beyond the postcolony (pp. 8–32). Cambridge Scholars Press.

Marais, K. (2018). Translation and development. In J. Evans & F. Fernandez (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of translation and politics (pp. 95–109). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315621289-7

Marais, K. (2019a). A (bio)semiotic theory of translation: The emergence of social-cultural reality. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315142319

Marais, K. (2019b). “What does development stand for?”: A socio-semiotic conceptualisation. Social Semiotics, 29(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2017.1392129

Marais, K., & Delgado Luchner, C. (2018). Motivating the translation development nexus: Exploring cases from the African Continent. The Translator, 24(4), 380–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2019.1594573

Nederveen Pieterse, J. (2009). Globalization and culture: Global mélange (2nd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield.

Nederveen Pieterse, J. (2010). Development theory: Deconstructions/reconstructions (2nd ed.). Sage. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446279083

Nussbaum, M. C. (2011). Creating capabilities: The human development approach. The Belknap Press of Harvard University. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674061200

Nussbaum, M. C., & Sen, A. (Eds.). (1993). The quality of life. Clarendon Press Oxford.

Olivier de Sardan, J.-P. (2005). Anthropology and development: Understanding contemporary social change. Zed Books.

Owen, J. R., & Westoby, P. (2012). The structure of dialogic practice within developmental work. Community Development, 43(3), 306–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330.2011.632093

Qin, L., & Li, M. J. (2020, December 21). 如何发挥澳门所长加快推进中葡平台建设?——写在澳门特区回归祖国21周年之际 [How to make use of Macao’s advantages to speed up the construction of the Macao Forum: For the 21st anniversary of the return of Macao SAR to the motherland]. Southern.com. https://ppfocus.com/sg/0/edc6bb2c1.html

Qu, S. B. (2021). 粤港澳大湾区语言生活状况报告 [Report on language and living conditions in the Greater Bay Area]. The Commercial Press.

Si, X. Z., & Guo, X. J. (2016). 试析中国翻译服务市场现状: 基于柠檬市场理论 [Analysis on the current situation of translation service market in China based on lemon market theory]. Chinese Translators Journal, 5, 65–69.

Si, X. Z., & Yao, Y. Z. (2014). 中国翻译产业研究: 产业经济学视角 [An industrial economic perspective on translation in China]. Chinese Translators Journal, 5, 67–71.

Todorova, M. (2018). Civil society in translation: Innovations to political discourse in Southeast Europe. The Translator, 24(4), 353–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2019.1586071

Toury, G. (1986). Translation: A cultural-semiotic perspective. In T. Sebeok & M. Danesi (Eds.), Encyclopedic dictionary of semiotics (February 2010 ed.). Mouton de Gruyter.

Troqe, R., & Pema, A. (2018). Translation in the Albanian communist and post-communist context from a semiotic perspective. The Translator, 24(4), 335–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2019.1586073

Wang, Y. B., Zeng, X. Y., & Duan, Y. Y. (2019). 粤港澳大湾区与新时代应用型高等教育 [A new era: applied higher education of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area]. Guangdong Higher Education Press.

Westoby, P., & Dowling, G. (2013). Theory and practice of dialogical community development: International perspectives. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203109946

Woetzel, J., Seong, J., Leung, N., Ngai, J., Manyika, J., Madgavkar, A., Lund, S., & Mironenko, A. (2019). China and the world: Inside the dynamics of a changing relationship. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/china/china-and-the-world-inside-the-dynamics-of-a-changing-relationship#

Xu, J. Z. (2014). 翻译经济学 [Translation Economics]. National Defense Industry Press.

Yu, H. (2019) The Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area in the making: development plan and challenges. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 34, 481–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2019.1679719

Yu, Y. L. (2015). 基于危机管理和可持续协调发展的MTI 教育质量监控模型 [A quality control model for MTI education on the basis of crisis management and sustainable and harmonious development]. Foreign Language Education, 36(5), 105–108.

Zhao, T. (2017). 翻译产业与区域经济发展的关联性探讨 [Study on the correlation between translation industry and regional economic development]. Economic Research Guide, 36, 52–53.

Zhou, C. S., & Zhang, G. J. (2020). 活力粤港澳大湾区之经济发展 [Dynamic Greater Bay Area: Economic development]. Guangdong Science and Technology Press.