Translation-mediated bilingual publishing as a development strategy: A content analysis of the language policies of peripheral scholarly journals

Xiangdong Li

Xi’an International Studies University, China

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7483-6076

Abstract

Local-language journals that include topics of regional interest and are published by regional institutions in the non-Anglophone world (peripheral journals, also called Global South journals in Development Studies) are underrepresented in major indexes and are struggling due to a lack of contributors, reviewers and financial support. Some have resorted to translation-mediated bilingual publishing as a development strategy to maintain their identity and increase their visibility and impact. To date, this strategy has received scant attention in the literature. The current research aims to explore why peripheral journals resort to the strategy and the ways in which it is put into practice. The overviews, instructions to authors and bilingually presented articles of 68 social science and humanities journals were reviewed through content analysis. The results suggest that the journals implement the strategy out of pragmatic and ideological concerns. It seems that the current use of translation as a development strategy is still an improvized mechanism instead of a standard model. Although many follow a similar pattern in some respects, there is a lack of management in the translation process and no agreed norms on cost coverage, translation strategy and presentation formats. This points to the necessity of further effort being expended to optimize the strategy in the future.

Keywords: peripheral journals, bilingual publishing, academic translation, development strategy, content analysis

1. Introduction

Academic journals have become the most important channels through which to record and disseminate knowledge (Pérez-Rodríguez et al., 2018). The quantity and quality of research outputs published in high-quality journals have become the most frequently used parameter with which to determine the hiring and promotion of academics, the distribution of research funds, the evaluation of departments and institutions, and the ranking of universities (Ordorika, 2018; Pérez-Rodríguez et al., 2018). Quantitative measures of journal quality were made possible through the creation of databases or indexes (e.g., Web of Science and Scopus) and citation-based metrics for journal ranking systems. Articles published in high-ranked indexed journals are considered to be of high quality and impact in research evaluation, which is true of the hard sciences and is becoming popular in the social sciences and humanities (Pérez-Rodríguez et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2021).

However, since such databases as the Web of Science and Scopus are biased towards journals published in the Anglophone world in respect of language, subject area, epistemology, and ideology (Klein & Chiang, 2004; Mongeon & Paul-Hus, 2016; Ordorika, 2018; Xu et al., 2021), most high-ranked indexed journals are published in English and include Anglophone concerns within their scope. Therefore, academics in the social sciences and humanities in non-Anglophone countries are disadvantaged in the evaluation of their research outputs. For one thing, they have to transcend the language barriers. For another, they need to shift their research foci from local concerns to those of international or Anglophone interest to fit the scope of the indexed journals (Ordorika, 2018). Despite such disadvantages and criticism of the bias of the databases, publish (in indexed journals) or perish is becoming the norm and ignorance of it comes at a high price in one’s career (Ibáñez-Martín, 2018). Consequently, academics submit their manuscripts preferably to indexed journals, especially high-ranked journals included in the Web of Science Core Collection Databases (SCI or Science Citation Index Expanded, SSCI or Social Sciences Citation Index, and A&HCI or Arts & Humanities Citation Index).

In contrast, journals published by regional institutions and excluded from SCI, SSCI or A&HCI are struggling to survive in a vicious cycle of a lack of submissions, a scarcity of reviewers and inadequate funding (Donovan, 2009, 2013; Mašić et al., 2016; Ordorika, 2018; Salager-Meyer, 2015). In the current study, journals published in English in Anglophone countries and indexed in SCI, SSCI or A&HCI are labelled “mainstream journals”, whereas those published in local languages in non-Anglophone countries and absent from SCI, SSCI or A&HCI (or present in the indexes but with a low ranking) are termed “peripheral journals” (Salager-Meyer, 2014). This unequal global relationship between the mainstream (core) and the peripheral (marginal) is known as Global North and Global South in Development Studies (Getahun et al., 2021). It should be acknowledged that making a dichotomic division between mainstream and periphery journals is not an easy undertaking. Mainstream and peripheral journals represent the two extreme poles on the core–periphery continuum. There are journals that lie in between – for example, those published in English in Anglophone countries and absent in major indexes, those published in English in non-Anglophone countries and missing in major indexes, and those published in major world languages (German, French or Spanish) and present in major indexes.

To alleviate the current constraints, peripheral journals are resorting to strategies such as free and open access of full-text articles, user-friendly websites, the dissemination of articles in social networks, a shift of scope from topics of local interest to those of both local and international interest, and new language policies (Ordorika, 2018; Pérez-Rodríguez et al., 2018).

The new language policies include a switch to using English as the only publishing language, publishing articles in either English or local languages depending on authors’ preference, or publishing articles in both English and local languages (bilingual publishing) (Kim & Chesnut, 2016; Ordorika, 2018). An English-only policy has side-effects (Ferguson, 2013; Mur-Dueñas, 2013; Van Parijs, 2004), although it rewards authors and journals (Cianflone, 2014; Li, 2018; Pulišelić & Petrak, 2006). Giving authors the freedom to choose between English and local languages is not effective as a way of changing the status of local languages in academic publishing because the majority of authors choose to submit articles in English out of pragmatic concerns, such as more international readers and greater chances of citation and promotion (Bocanegra-Valle, 2014; Fuentes & Gómez Soler, 2017). Therefore, some journals have resorted to a policy of bilingual publishing, although the number of journals practising such a policy is small because articles need to be translated and published in both English and local languages, which is both labour-intensive and costly (Morley & Kerans, 2013).

The key to successful bilingual publishing lies in translation (Bartholomäus et al., 2015). Translation-mediated English publishing is common and plays an essential role in helping non-English native-speakers transcend the linguistic barriers (Bennett, 2013a; Burgess & Lillis, 2013; DiGiacomo, 2013; Farley, 2018; Kim, 2019; Lillis & Curry, 2006; McGrath, 2014; Salager-Meyer, 2008; Sionis, 1995). However, translation in academic publishing is rarely explored due to its invisibility (Pisanski Peterlin, 2019). Research on the translation-mediated production of bilingual journals is even rarer. Morley and Kerans (2013) shared their understanding of the reasons for and practices of bilingual publishing based on their experiences of translating medical journals. Another published account is that of Bartholomäus et al. (2015), who surveyed the editors of eight medical journals and the authors and translators of one of the journals. They found that bilingual publishing improves impact factors and attracts authors, that authors are satisfied with the translated texts, and that translators reported specialized terminology as the main obstacle. To date, no studies have examined why and how translation is used by social sciences and humanities journals as a development strategy in bilingual publishing.

Translating articles in the social sciences and humanities is more challenging than translating those in the medical and natural sciences. The first difficulty is that it requires translators to be familiar with two academic literacies because languages are used as a way of constructing knowledge in the social sciences and humanities (Kuteeva, 2014). There is no absolute equivalence between the two literacies to be mediated through translation. The next challenge lies in the difficulty of bridging the differences between two academic literacies by adapting the academic norms of the source language to those of the target language. Since academic conventions and epistemological traditions are culture-specific, academic norms such as rhetorical sequencing and the structures of scholarly discourses vary from culture to culture (Connor, 1996; Flowerdew, 2008; Hoorickx-Raucq, 2005; Martín-Martín, 2003; Mauranen, 1993; Pisanski Peterlin, 2005; Siepmann, 2006). And if too many adaptations are made, the source academic traditions will be invisible in target articles. If no adaptations are made, the foreign academic conventions will read as weird and less acceptable among readers of the target articles. Thus, the communication of knowledge from one social order to another through translation is not a neutral process but a political negotiation where the acceptable extent of adaptation depends on the power dynamics between English and the local language concerned (Kanneh, 1997; Wilmot & Tietze, 2020).

Another challenge is related to the content of the social sciences and humanities studies. In the medical and natural sciences, many terms and concepts are universal because they originate from the Anglophone world and are accepted by academics in local communities, and essential information is delivered through data presentation which takes non-linguistic forms – such as tables, figures or equations (McKenny & Bennett, 2011). In contrast, the content and concepts in the social sciences and humanities are specific to and embedded in the contexts, languages, cultures and traditions of local societies and are constructed through local epistemological traditions (Bennett, 2013b; Chan, 2016; Duszak, 1997; McKenny & Bennett, 2011). Information is mainly delivered through convincing interpretations and arguments which are culture- and language-specific (Schluer, 2014). What is present or accepted in source articles, be it a concept or a term, might be absent and frowned upon in target articles, which also poses difficulties for translators.

Despite the use of translation-mediated bilingual publishing as a development strategy among social sciences and humanities journals and the relevant challenges, it is a rarely explored area in the current literature. Why do social sciences and humanities journals resort to bilingual publishing? How do they practise translation-mediated bilingual publishing (translation directions, coordination and management, quality control, translation cost, translator acknowledgement, translation strategies, and the format of presenting the two versions of articles)? Such questions are yet to be answered.

Against such a background, the purpose of this article is to explore the use of translation as a development strategy among peripheral journals (also called Global South journals in Development Studies) in the social sciences and humanities. The research questions this study set out to answer are:

· What are the motivations of translation-mediated bilingual publishing?

· How is translation used by peripheral journals as a development strategy?

It is hoped that this study may contribute to a better understanding of why and how peripheral journals use translation strategically as a response to constraints in their development (Marais, 2018).

2. Translation-mediated bilingual publishing as a development strategy

The advantages of a bilingual publishing policy are compared with those of the English-only and the English-or-local-language policy in Figure 1.

An English-only policy promotes the worldwide spread of knowledge, rewards authors and institutions through research evaluation, and increases journals’ chances of international readership, visibility, citations, funding, and indexation (Cianflone, 2014; Di Bitetti & Ferreras, 2016; Li, 2018; Moed et al., 2020; Pulišelić & Petrak, 2006; Salager-Meyer, 2008). The cost of this policy is that it abandons journals’ cultural identities and local ways of knowledge construction, and reinforces the homogenizing process of globalization (Ferguson, 2013; Mur-Dueñas, 2013; Van Parijs, 2004).

A multilingual policy allows authors to choose their favourite languages and therefore encourages multilingualism and diversity. However, this either–or solution allows each article to serve only either the local or the international community. Worse still, more authors are choosing English as the default language (Bocanegra-Valle, 2014; Fuentes & Gómez Soler, 2017), reducing the policy to an empty slogan.

Figure 1

Translation-mediated bilingual publishing in contrast to the other two strategies

In contrast, translation-mediated bilingual publishing as a strategy is able to offset the drawbacks of the abovementioned policies. It displays an inclusive attitude and gives equal treatment to local languages and English, tolerating the parallel use of English and local languages as the academic lingua franca and therefore promoting multiculturalism and multilingualism. Moreover, it helps to preserve a pluralistic community in which different rhetorical and intellectual conventions of knowledge construction and dissemination coexist in harmony and enrich and complement one another (Espinet et al., 2015; López-Navarro et al., 2015). In addition, it increases journals’ international visibility, impact, and scope of authorship because knowledge can be disseminated to both the local and the international community (Bartholomäus et al., 2015; Espinet et al., 2015; Kuteeva & Mauranen, 2014; Salager-Meyer, 2008).

In the present article, translation as a development strategy refers to the use of translation as an instrument for transformation. In this paradigm, translation is approached from an activist perspective: priorities are given to the way practitioners attempt to bring about social changes, resolve power asymmetries, or resist cultural domination through translation (Boéri, 2020).

Language can be used to bring about social change. For example, local novelists may elevate the status of a vernacular language through the use of that language (Leclerc, 2005). Whereas using a vernacular language marginalizes them, using an international language means a total disappearance of identity. To respond to this ambivalence, novelists can resort to hybridity, weaving elements of local languages into their works written in a dominant international language. In this way, the vernacular language gains recognition and visibility in the global sphere without totally losing its local identity. This is an example of language use as a development strategy.

But translation can also lead to social transformation. When translating works by local novelists, similar ambivalence exists regarding strategy (Leclerc, 2005). Translators can adapt local norms in their novels to the expectations of the target readers, and in this way the local norms are assimilated. Alternatively, translators can preserve and reproduce the local norms as they are in the target texts, but by doing so they put the reception of the target texts at risk because target readers may not be aware of the distinctive linguistic and social norms of the source texts and they may accordingly evaluate the target texts on the basis of their own expectations. Which translation strategy is used depends on the context and the translator who needs to identify the right distance and strike the right balance between two cultures and languages. No matter which strategy is implemented, it cannot be denied that translators play the role of activists who can control the extent to which distinctive realities in the source texts are preserved or filtered.

Specifically, the translation practice discussed in the present article – that is, translation-mediated bilingual publishing – is used to bring about at least two changes. One is about the scope of the dissemination of knowledge produced by local scholars. Without translation, knowledge can be disseminated only either in the international community if English is the default language of publication or in the local community if local languages are used as languages of publication. With translation-mediated bilingual publishing, local knowledge can be disseminated to both international and local communities. The other change concerns legitimizing the status of local languages as a way of knowledge construction and presentation. Without translation, if English is used as the default language of publication, local languages as alternative ways of knowledge construction are entirely ignored. If local languages are languages of publication, their status as avenues of knowledge construction could be recognized, but this scenario is less likely to occur because authors prefer to publish in indexed English journals that expose their contributions to a broader readership. With translation-mediated bilingual publishing, the status of local languages as alternative ways of knowledge construction is preserved without the cost of limiting the readership.

The above two changes are both associated with the impact of translation. But changes can also be expected during the translation process where translators play the role of activists to manipulate the extent to which the local norms of knowledge construction are preserved or filtered. They can either filter what is foreign to target readers and adapt it to satisfy readers’ expectations or preserve what is unique and distinctive in the source texts. In translation-mediated monolingual (English) publishing, translated English versions are evaluated by reviewers and editors against the way knowledge is constructed in the Anglophone world before they are accepted for publication. To enable texts to pass peer reviews, translators are more likely to adapt foreign elements that are different from the Anglophone standard because failure to do so may be associated with the academic incompetence of authors (Bennett, 2013a; Pisanski Peterlin, 2008). Such a domestication or adaptation strategy is widely used by translators (Bennett, 2013a; Pisanski Peterlin, 2016; Siepmann, 2006). In contrast, in translation-mediated bilingual publishing, it is the original source texts that are evaluated by reviewers and editors familiar with the local rhetorical norms and ways of knowledge construction. The original articles are accepted for publication before they are translated, as is required by most journals. With no pressure to satisfy reviewers’ expectations of the Anglophone standard of knowledge construction and presentation, translators are more likely to preserve the distinctive local features of the local texts. As a result, the local language articles and their English versions are in parallel with each other. Therefore, in translation-mediated bilingual publishing, translators increase the recognition and visibility of local alternatives of knowledge construction and presentation in the international community.

3. Methodology

This research is intended to examine the use of translation as a development strategy by peripheral social sciences and humanities journals. Specifically, it aims to explore why peripheral journals resort to translation-mediated bilingual publishing and how translation is practised as a development strategy (translation directions, coordination and management, quality control, translation cost, translator acknowledgement, translation strategies, and format of presenting the two versions of articles).

Content analysis (Jaspal, 2020) was used to analyse the websites of 68 journals that use bilingual publishing as a strategy. To this end, cluster sampling was used: the researcher searched four international and regional databases one by one (Scopus, DergiPark akademik, OpenEdition Journals, and ERIH PLUS), using certain query strings (language: English and local language; discipline: social sciences and arts and humanities; year range: 2015–2020; document type: article). For each query, a long list of articles was generated. Then the websites of the journals publishing the articles were reviewed one by one to check whether bilingual publishing is the policy. After reviewing the websites of 1,033 journals (675 from Scopus, 69 from DergiPark akademik, 131 from OpenEdition Journals, and 158 from ERIH PLUS), 68 met the criteria of bilingual publishing and were included in the analysis (51 from Scopus, one from DergiPark akademik, 14 from OpenEdition Journals, and two from ERIH PLUS). Descriptions of the profiles of the journals are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Descriptions of the journal profiles

|

Disciplines |

Education |

23 |

|

Anthropology |

5 |

|

|

Archaeology |

5 |

|

|

History |

4 |

|

|

Linguistics |

4 |

|

|

Psychology |

4 |

|

|

Geography |

3 |

|

|

Sociology |

3 |

|

|

Art |

2 |

|

|

Communication |

2 |

|

|

Cultural studies |

2 |

|

|

Demography |

2 |

|

|

Film studies |

2 |

|

|

Gender studies |

2 |

|

|

Law |

1 |

|

|

Management |

1 |

|

|

Political science |

1 |

|

|

Tourism |

1 |

|

|

Urban studies |

1 |

|

|

Countries |

France |

16 |

|

Spain |

15 |

|

|

Brazil |

12 |

|

|

Croatia |

6 |

|

|

Turkey |

4 |

|

|

Belgium |

2 |

|

|

Russia |

2 |

|

|

Portugal |

2 |

|

|

Slovenia |

2 |

|

|

Germany |

1 |

|

|

Macedonia |

1 |

|

|

Mexico |

1 |

|

|

Netherlands |

1 |

|

|

Romania |

1 |

|

|

Serbia |

1 |

|

|

Switzerland |

1 |

|

|

Journal history |

51 years or more |

11 |

|

41–50 years |

9 |

|

|

31–40 years |

15 |

|

|

21–30 years |

17 |

|

|

11–20 years |

11 |

|

|

1–10 years |

5 |

|

|

Availability |

Open access |

55 |

|

Partial open access |

13 |

|

|

Publisher |

Local publisher |

61 |

|

Local and international collaboration |

7 |

Table 1 reveals three points about bilingual publishing. The first is that bilingual journals do exist in the humanities and social sciences. So far, the literature has focused on the translation of medical journals only. Translating for humanities and social sciences journals is more challenging than translating medical journals because the differences in rhetorical norms and knowledge construction between local and international academic communities in the humanities and social sciences are more dramatic than those between local and international academic communities in the medical sciences. This justifies the necessity of the current research and points to future directions for exploring more of this under-researched area.

The second is that most bilingual journals are published in certain cultural–geographic countries where Romance languages (Spanish, French, etc.) are spoken. Two factors might have been responsible for this trend. One is related to the attitudes of academic communities towards the necessity of disseminating their research outputs bilingually. According to Hempel (2011), the German-speaking communities are strongly convinced that German should be used as the legal publishing language. In this academic community, publishing in English and adapting traditional German writing conventions to the Anglophone norms are rejected. Here, the value of published works is not based on their publishing language. Similar beliefs are held by Italian scholars, although their stance to preserving the status of Italian as a legal language of scholarly communication is not as firm as that of their German-speaking counterparts. They worry about the future of Italian as an academic language, but they can hardly resort to English because of existing language barriers. Also, financial support is partially responsible for this approach.

France and Spain are the top two countries with the largest number of bilingual journals. Many of the journals are supported financially. For example, more than half of the bilingual journals published in France are supported by the CNRS (Institut des Sciences Humaines et Sociales, Institute of Human and Social Sciences), which aims to promote the internationalization of studies in the humanities and the social sciences in France. Similarly, many of those published in Spain are supported by the FIA (Fundación Infancia y Aprendizaje, Childhood and Learning Foundation), a not-for-profit foundation dedicated to disseminating scientific knowledge about psychology and education.

Another point highlighted in Table 1 is that the number of bilingual journals published in education is more than that in other disciplines. Moreover, the attitudes of scholars in a specific discipline can influence the choice of publishing languages. For example, while the archaeology discipline in Germany and Italy will not transition to English as the publishing language soon, some others are already on their way to doing so due to the influence of social trends (Hempel, 2011). As indicated in Table 1, education belongs to the discipline where there is an emerging trend to publish research outputs bilingually.

The 68 journals’ overviews, instructions to authors, publishing policies, bilingually presented articles, editorial team, and other information available on their websites were examined to answer the questions in Table 2.

Table 2

Coding schemes

|

Categories |

Coding questions (levels) |

||

|

Motivation |

Why do the journals resort to bilingual publishing? (Open coding aided by Nvivo 12) |

||

|

Translation direction |

Which are the directions of translation? |

Bidirectional translation between English and local language |

|

|

Translation from English into local language |

|||

|

Translation from local language into English |

|||

|

Coordination and management |

When are the articles translated? |

After acceptance |

|

|

At the time of submission |

|||

|

After publication |

|||

|

Not stated |

|||

|

Who is responsible for looking for translators? |

Author |

||

|

Journal |

|||

|

Not stated |

|||

|

Are there editorial staff responsible for translation management? |

Yes |

||

|

No |

|||

|

Translation quality control |

Are there any requirements for translator qualifications? |

Yes |

|

|

No |

|||

|

Are there any guidelines for translation? |

Yes |

||

|

Not stated |

|||

|

Are there measures to ensure translation quality? |

Yes |

||

|

Not stated |

|||

|

Translator acknowledgement |

Are the translators credited in the journals? |

Yes |

|

|

No |

|||

|

Cost |

Who covers the translation cost? |

Author |

|

|

Journal |

|||

|

Not stated |

|||

|

Translation strategy |

All |

||

|

Selected |

|||

|

Presentation |

How are the translated articles presented in relation to the originals? |

Side by side in the same document |

|

|

One after the other in the same document |

|||

|

In different documents |

|||

Information related to motivation was recorded in separate documents and then analysed inductively in Nvivo 12. There was no prior development of specific coding schemes: open coding was conducted to allow main themes to emerge. The nodes and their frequencies were reported on.

For information related to other questions an Excel spreadsheet was used to record the coding results and descriptive statistics were used to calculate their frequencies.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Motivation

The first question the current research aims to explore is related to the motivations for using translation-mediated bilingual publishing.

As can be seen in Table 3, these motivations fall into two categories: pragmatic and ideological. The top two pragmatic motivations are to maximize article dissemination and readership and to promote the internationalization, visibility, and impact of the journal, which are mentioned by 19 (28%) and 7 (10%) out of the 68 journals. The top three ideological motivations are to increase the exchange of knowledge between the local and international community (9, or 13%), to maintain the identity of the journal (4, or 6%), and to encourage multilingualism (4; or 6%).

Table 3

Motivations

|

Motivations |

No. of journals |

Example |

|

Pragmatic motivations |

||

|

19 (28%) |

“… provide authors with maximum exposure of their works …” (Estudios de Psicología) |

|

|

2. Promote the internationalization, visibility and impact of the journal |

7 (10%) |

“… offered our publication not only regional or national, but also international character ...” (Transsylvania Nostra) |

|

3. Attract more and better submissions |

1 (1.5%) |

“… attract more and better research, which will result proportionally in the quality of the publication …” (Comunicar) |

|

Ideological motivations |

||

|

1. Increase the exchange of knowledge between local and international communities |

9 (13%) |

“… building a bridge between scholars from around the world with those operating in the Central and South-East Europe …” (Revus) |

|

2. Maintain the identity of the journal |

4 (6%) |

“… a bilingual edition … remaining faithful to the international ambitions …, expanding the diffusion of our historiographical project without sacrificing our identity …” (Annales) |

|

3. Encourage multilingualism |

4 (6%) |

“… given the importance of the English language as a scientific communication vehicle and additionally in this case the international importance of the Spanish language …” (Revista de Educación) |

|

4. Preserve the advantages of local scholars writing in local language |

2 (3%) |

“… everyone can write in his/her native language, which allows for the expression of more nuance than in a more or less well controlled foreign language, …” (Via Tourism Review) |

|

5. Raise the international visibility and reputation of local disciplines and communities |

2 (3%) |

“… promote the internationalisation of French human and social sciences …” (Clio) |

|

6. Respond to the degradation of local language as a means of knowledge construction and dissemination |

2 (3%) |

“… a gradual move away from French as an international language of scientific communication. Faced with these transformations, the editorial board … explore new possibilities and forms of publication …” (Annales) |

The results suggest that peripheral journals choose to publish bilingually for both pragmatic and ideological reasons. They care about not only their own development, but also the academic ecology and multilingualism. This is different from the motivations determining non-anglophone individual scholars’ language choice between English and local languages, most of which are pragmatic, such as intended readership, research topic, academic connection, institutional research evaluation policy, language proficiency, career development, funding opportunities, and the availability of funding for translation (Baldauf, 2001; Cho, 2009; Fuentes & Gómez Soler, 2017; Gentil & Séror, 2014; McGrath, 2014; Muresan & Pérez-Llantada, 2014; Schluer, 2014; Warchał & Zakrajewski, 2021; Zheng & Gao, 2016).

It could be predicted that, if successful, bilingual publishing as a development strategy may bring about benefits to the academic ecology and multilingualism and also to the growth of peripheral journals.

In contrast, translation-mediated bilingual publishing encourages linguistic and epistemological pluralism because both English and local languages are used to present knowledge. In addition, articles in local languages are submitted, reviewed, and accepted before they are translated into English. In other words, the purpose of translation is not to survive the evaluation of the Anglophone community but to disseminate the research outputs to a broader readership. Therefore, in bilingual publishing, translators are not under so much pressure to domesticate rhetorical and epistemological conventions as they are when translating for English-only publishing. Consequently, non-Anglophone rhetorical and epistemological conventions stand a better chance of being preserved in the translated versions.

However, to what extent non-Anglophone rhetorical and epistemological conventions can be preserved depends on other factors too. This is because the choice between domestication and foreignization is driven by ideological and pragmatic motives. Ideologically, translation between English and local languages is not a purely linguistic activity but a mediation effort between conflicting ideological identities. Owing to the unequal power relations between local languages and English, translators tend to use the foreignizing strategy if English is the source language and the domesticating strategy if it is the target language (Campbell, 2005). Evidence suggests that domestication is a common strategy in the translation of academic works from local languages to English (Bennett, 2013a; Pisanski Peterlin, 2016; Siepmann, 2006).

Pragmatically, individual translators may not think of their mediation as an ideological issue but consider it to be merely a language service. They focus on how best to help their clients disseminate their research outputs to the Anglophone community. When they translate, they domesticate rhetorical and epistemological conventions so that target articles are well received among English-speaking colleagues – which is the first step towards citation and recognition. If they choose the foreignization strategy, target English readers may associate the exotic target discourses with authors’ academic incompetence (Bennett, 2013a; Pisanski Peterlin, 2008) or even with the translation quality or the translator’s credentials. This may explain why the domestication of rhetorical conventions to those of the target culture also exists in the translation of scholarly articles between other language pairs, such as German and Italian (Hempel, 2010; Toscher, 2019).

No matter which strategy is implemented, translation-mediated bilingual publishing can promote linguistic and epistemological pluralism. If foreignization is used, both the languages and the epistemological traditions of non-Anglophone communities are maintained; it can also serve to preserve epistemological and linguistic diversity and ensure equal status between non-Anglophone and Anglophone communities. The downside is that the reception of translated English articles might be challenging for Anglophone scholars who are not bi-literate. Moreover, if domestication is used to satisfy target readers’ expectations when translating scholarly articles into English, non-Anglophone epistemological traditions are likely to be absent in the English versions, although they will still be present in the local-language versions, visible to local communities and those who are bi-literate in the Anglophone community. Another advantage of the bilingual publishing approach is that the languages of non-Anglophone communities can be used as a way of knowledge construction. In this way, the use of domestication preserves linguistic diversity and partially maintains epistemological diversity. Unfortunately, though, it cannot help to change the power relations between non-Anglophone and Anglophone academic communities.

When choosing strategies, translators are faced with ambivalence (Bennett, 2013a; McKenny & Bennett, 2011): on the one hand, foreignization retains local rhetorical and epistemological conventions for pluralism and equal status, but, on the other, it exposes translated articles to the risk of denial of their values and credibility in the Anglophone community. And whereas domestication does tailor non-Anglophone rhetorical and stylistic norms to Anglophone standards for better chances of recognition and impact, it unwittingly becomes an accomplice in reinforcing the carnivore role of English and in defying local alternatives of knowledge construction. As a possible solution, translators may brief English-language readers, perhaps in the form of endnotes in the translated versions, about the problems encountered during the translation process and how attempts were made to resolve them through either domestication or foreignization. The purpose of such briefing would be to inform readers who are not bi-literate either about the existence of alternative forms of rhetorical and epistemological conventions when they are domesticated or about the origins of the exoticness of the translated discourses when non-Anglophone rhetorical and epistemological conventions are not adapted to Anglophone conventions. The use of translator notes would also be a way of educating readers that knowledge construction and presentation is culture-specific.

That said, compared to reinforcing the trend of English-only publishing, the translation-mediated bilingual publishing policy helps to promote linguistic and epistemological pluralism.

It should be admitted, though, that there are plausible situations where translation-mediated bilingual publishing may not serve to preserve epistemological pluralism. In monolingual (English) publishing, following the English standards and conventions is the only valid way of knowledge construction and presentation (Uzuner, 2008). In such a situation, the evaluators (editors and reviewers) are unsympathetic to the barriers that non-Anglophone authors encounter and may not even be aware of the existence of alternative ways of knowledge construction and presentation (Bennett, 2013a). But with the impact of English standards and conventions on academic epistemology increasing, non-Anglophone scholars may conform to them either consciously or subconsciously when they write in English or even in their mother tongues (Bennett, 2013a, 2013b). However, if they avoid the local rhetorical and epistemological traditions when writing in local languages in the first place, translating them and publishing the bilingual versions will not help to preserve epistemological diversity.

When bilingually published journals – in particular those that are not included in the major indexes and are not providing translation services for free (as the findings indicate in the next section of this article) – fail to meet the expectations of individual scholars (Warchał & Zakrajewski, 2021), they may still find it hard to attract submissions. Therefore, to increase their chances of success, they need financial support from local governments or other institutions so that they can provide sufficient resources to attract contributors – for example, by offering authors free translation services.

4.2. Translation practice

The second question the current research is intended to explore is how translation-mediated bilingual publishing is practised by peripheral journals as a strategy. In this section, the author presents results and discussions regarding translation direction, coordination and management, translation quality control, translator acknowledgement and cost, translation strategy, and presentation.

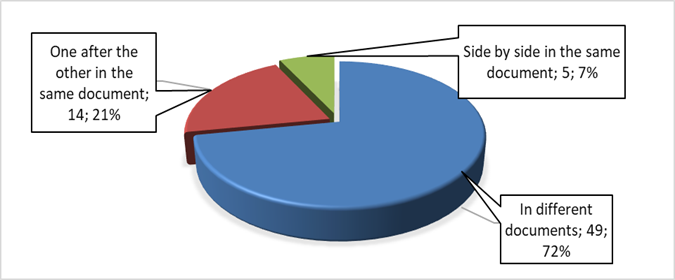

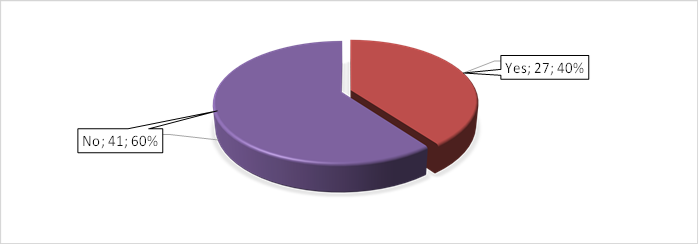

As far as translation direction is concerned, most journals practise bidirectional translation. As can be seen in Figure 2, the majority of the journals (49 out of 68, or 72%) involve bidirectional translation, that is, translation both from and into English and local languages. This is consistent with the bilingual policy and it indicates that the majority of journals allow authors to submit their contributions in English, a regional foreign language, or a local language.

Figure 2

Translation directions

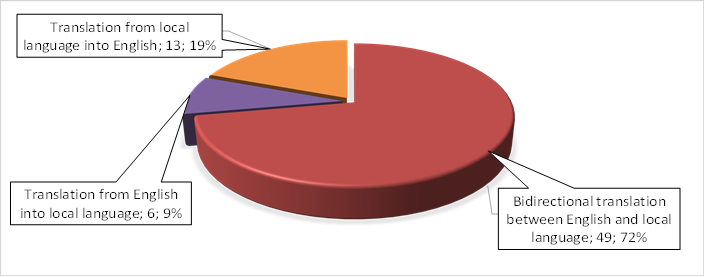

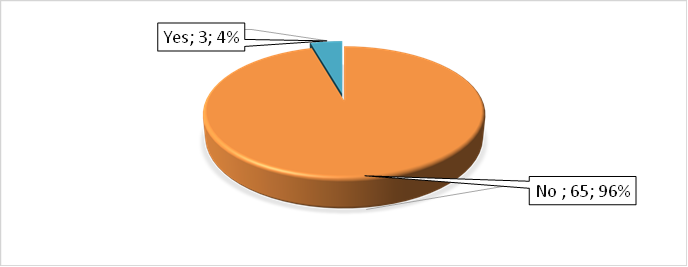

Regarding the timing of translation, as is displayed in Figure 3, most of the 68 journals (38, or 56%) want the translated versions after the acceptance of the original articles. Ten of the journals (15%) require authors to submit both versions of articles at the time of submission, whereas four (6%) provide the translated articles after the original articles are published. In other words, most journals follow a simultaneous publication model where the original and the translated articles are published at the same time. This finding is not consistent with that of Morley & Kerans (2013), who reported that among bilingually published medical journals a sequential model pertains where the publication of original articles precedes the publication of the translated articles. The simultaneous model may pose challenges for translation management because the untimely submission of the translated version may delay the publication of the original articles. However, the advantage is that any errors in the original articles identified in the translation process may be corrected timeously before getting published.

Figure 3

Time of translation

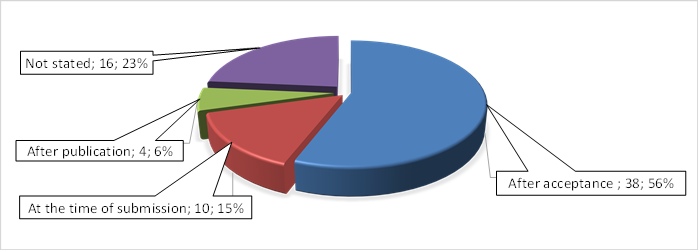

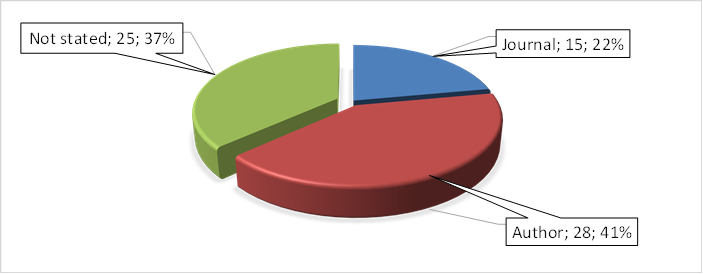

The responsibility for securing translators varies widely. As is shown in Figure 4, 18 journals (26%) make it clear that authors are responsible for engaging translators, while 25 journals (37%) seek the services of translators themselves. Since non-anglophone scholars’ language choices in publishing are determined by pragmatic factors instead of ideological considerations (Baldauf, 2001; Cho, 2009; Fuentes & Gómez Soler, 2017; Gentil & Séror, 2014; McGrath, 2014; Muresan & Pérez-Llantada, 2014; Schluer, 2014; Warchał & Zakrajewski, 2021; Zheng & Gao, 2016), giving authors the additional burden of finding translators (particularly if they are not funded) may have a negative impact on their will to submit their articles to those journals.

Figure 4

Responsibility for looking for translators

Fewer than half of the journals have designated editorial staff responsible for translation management. As shown in Figure 5, only 27 of the journals (40%) make it clear that they have editorial staff to manage the translation process. Without designated staff as coordinators, smooth and timely communication between authors, translators and editors may be difficult.

Figure 5

Designation of editorial staff for translation management

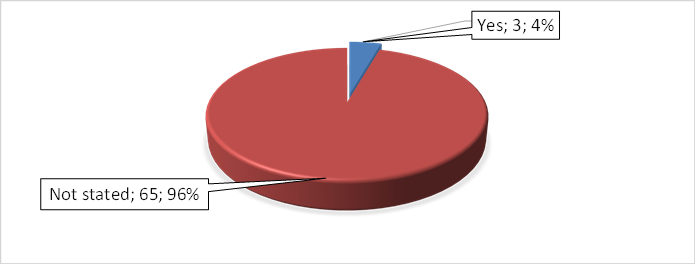

As for quality control, only a few journals mention their requirements regarding translator qualifications. As displayed in Figure 6, most of the journals (65, or 96%) fail to specify who qualify to be the translators of their articles. Ideally, the translation of academic articles should be done by experts with adequate literacy in relevant disciplines and knowledge of the rhetorical norms and styles in the two languages involved. But there is no consensus as to the optimal strategy for academic translation, foreignization, domestication, or a combination of them. Although foreignization seems to be a better choice for preserving rhetorical and epistemological pluralism, domestication is the approach that is being used (Bennett, 2013a; Pisanski Peterlin, 2016; Siepmann, 2006). No matter which is preferred, translators should be literate in two systems of rhetorical and epistemological conventions.

Similarly, most of the journals provide no guidelines on translation. Only three (4%) give instructions to ensure translation quality (Figure 7), while measures to ensure translation quality are ignored by most journals (Figure 8). Only 18 journals (26%) mention what is done to deal with the translation work to ensure translation quality. This is crucial for peripheral journals in the social sciences and humanities, where translating academic texts is a challenging task. In the natural sciences, knowledge is mainly constructed through the presentation of hard data; culture, context, and language have a less vital impact. Therefore, the translation of scientific articles between local languages and English does not require many changes in academic conventions. In contrast, in the social sciences and humanities, context, culture, and linguistic and rhetorical norms play an essential role in knowledge construction: Here, local and international communities usually have different academic literacies (Kuteeva, 2014). Therefore, in some cases, extensive domestication is required in translation to tailor the academic conventions of local languages to meet those of English (Bennett, 2013a). Moreover, articles accepted for publication may deal with topics of local concern. They may be written the way source cultures and conventions construct knowledge and may not be consistent with the expectations of target readers regarding argumentation. There might also be concepts and culturally loaded elements that have no equivalents in the target culture. For those reasons, translators encounter more challenges in reproducing accurate and readable articles compared to those who translate articles in medicine and the hard sciences. However, issues that may arise from translation are ignored by most journals – for example, the strategies that are appropriate when dealing with differences in culture, conventions and intellectual norms and to what extent or in which cases gloss translation (i.e., literal reproduction of the form and content of the source article) is acceptable. If no guidelines are provided and dealing with the issues is left to translators’ intuition, consistency in translation quality is difficult to maintain.

Figure 6

Requirements of translator qualifications

Figure 7

Guidelines for translation

Figure 8

Measures to ensure translation quality

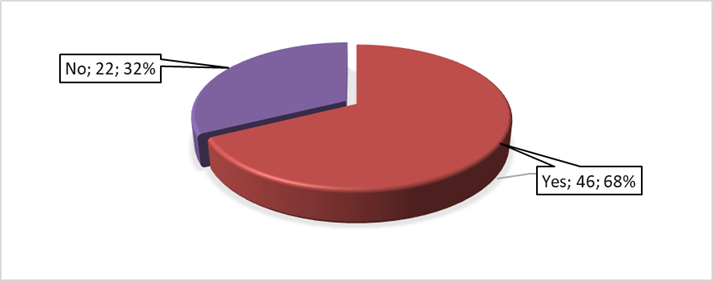

More than half of the journals acknowledge the translators: as is presented in Figure 9, 46 journals (68%) acknowledge their translators in one way or another. Some are acknowledged in the first-page footnotes, some in endnotes, and yet others in journal prefaces. This is different from translation-mediated monolingual publishing, where authors resort to translators to have their local-language articles translated into English before submitting them to an English-only journal. In such cases, the translators do not seek acknowledgement (Burrough-Boenisch, 2019) and are usually not credited (Franco Aixelá, 2004).

The invisibility of translators in English-only journals may be related to the unbalanced status of English vis-à-vis local languages. The supremacy of English over local languages as the only legitimate language of knowledge construction and dissemination assumes the Anglophone way of knowledge construction to be universal, devaluing the existence and contribution of their local alternatives. English-only publishing takes it for granted that knowledge is constructed in English and that translation is both unnecessary and invisible, even though translators make creative decisions to produce new texts and bridge two systems of understanding, interpreting, and producing knowledge (Luo & Hyland, 2019; Wilmot & Tietze, 2020).

Figure 9

Translator acknowledgement

The coverage of translation costs varies too. Whereas 15 journals (22%) cover the translation cost, many more journals (28, or 41%) leave the cost to the authors to cover (Figure 10). Owing to the scarcity of translators with expertise in domain knowledge and academic discourse, the translation of journal articles is expensive. If journals covered the cost, it would be a challenge to their budget; this may explain why more journals choose to leave the cost to authors. However, in this latter arrangement, translation quality is beyond the control of the journals (Morley & Kerans, 2013). Another negative impact is that it would be difficult for those journals to attract contributions because research indicates that the availability of funding for translation services influences authors’ choice of publication language between English or local languages (Warchał & Zakrajewski, 2021). If authors are not funded by their institutions to cover the translation fees, they may be discouraged from making contributions to bilingually published journals. One strategy that could contribute to reducing the cost of translation is being selective about the articles to be translated (Morley & Kerans, 2013). This decision would be related to the translation strategy of the peripheral journals, which is reported on below.

Figure 10

Coverage of translation cost

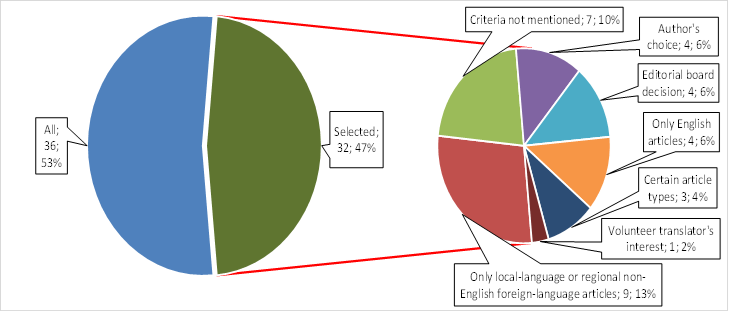

The journals use a variety of translation strategies. As can be seen in Figure 11, 36 of the journals (53%) translate all their articles, whereas 32 (47%) are selective about those to translate. The criteria for selecting articles to be translated take the form of different standards. This decision often depends on the choices of authors or editorial boards, the interests of volunteer translators, the article types (e.g., only state-of-the-art articles or empirical articles are translated), or the language (only either English articles or local-language articles are translated). As mentioned previously, selective translation can be used as a strategy to reduce the translation cost if the translation of all the articles poses challenges to the journals’ budgets.

Another strategy suggested in the literature is translation on demand (Morley & Kerans, 2013). According to this strategy, journals translate only article abstracts which provide information for readers to decide whether they would send requests to have the full articles translated or not. This strategy is not used in the current translation practice of peripheral journals.

Figure 11

Translation strategies of bilingual publishing

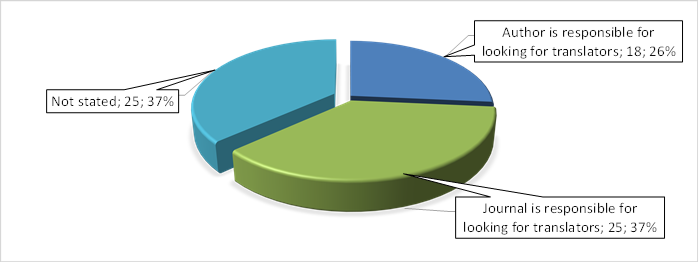

The presentation of the original and translated articles takes different forms (Figure 12). Whereas most of the journals (49, or 72%) choose to place the original and translated articles in different documents for readers to download separately, others put both versions in one document. In the latter case, some arrange the two versions one after the other (14, or 21%) and others present them side by side as parallel texts (5, or 7%). Ideally, assigning separate DOI numbers and indexing both versions would increase their visibility. However, since only one version is visible to search engines and accessible through the DOI link (Aragón-Vargas, 2014), arranging the original and translated articles in the same document, either one after the other or side by side, may increase the chances of bringing both versions within the reach of both international and local readers. If they are placed in separate documents, scholars reading them may not know that the other version exists.

Figure 12

Presentation of the translated article

To sum up, it seems that the use of translation as a development strategy among the peripheral journals surveyed is currently an improvized mechanism instead of a standard model. Although many follow a similar pattern in the time of translation and translator acknowledgement, there is a lack of management of the translation process (e.g., designated staff for translation management, guidelines for translation, and instructions on translator qualifications and quality control measures). The guidelines also vary in the areas of cost coverage, translation strategy, and presentation formats. This points to the scant attention being paid to the use of translation as a development strategy in bilingual publishing to date in Translation Studies. More effort should be made to optimize the translation practices in bilingual publishing so as to improve the efficacy of articles in both versions.

5. Conclusions

The current research is intended to explore the reasons that the peripheral journals that publish the social sciences and humanities use translation as a development strategy to achieve bilingual publication and how it is put into practice.

The results suggest that the journals have resorted to translation-mediated bilingual publishing out of both pragmatic and ideological motivations. The former includes maximizing article dissemination and readership and promoting the internationalization, visibility, and impact of the journal. The latter consists of increasing the exchange of knowledge between the local and international communities, maintaining the identity of the journal, and encouraging multilingualism.

The results reveal that the use of translation as a development strategy among the peripheral journals is still an improvized mechanism instead of a standard model that they all subscribe to. It has been found that more than half of them practise bidirectional translation, require the translated version to be submitted after acceptance of the original article, and acknowledge the translators in one way or another, although there are still others that follow different paths in those respects. There is a lack of designated editorial staff who are responsible for translation management; detailed requirements of translator qualifications are largely wanting, and there is a dearth of translation guidelines. The journals vary in assigning the responsibility for engaging translators, in covering translation costs, in their translation strategies, and in the formats in which original and translated articles are presented. The inadequacy of the current mechanism points to future efforts being necessary to optimize the use of translation as a strategy in bilingual publishing.

Because of the limited size of the pool of journals, any efforts to generalize the current findings should be approached with caution. Although the researcher has tried every means to access as many journals as possible, only 68 journals that met the research aim were included due to the difficulty of identifying bilingually published humanities and social sciences journals in the currently available databases. Furthermore, since only humanities and social sciences journals were included, the findings may not necessarily apply to journals in other fields, such as medicine or the hard sciences.

Despite these limitations, it is hoped that the current exploration – an initial attempt to examine the use of translation-mediated bilingual publishing as a development strategy among humanities and social sciences journals – may elicit further evidence on the contributions of translation to increasing linguistic and epistemological pluralism and international visibility without sacrificing local rhetorical and linguistic norms of knowledge construction. It is hoped, too, that additional evidence garnered may reveal the ways in which translation is being practised to realize such contributions and the nature of the associated problems that continue to exist.

References

Aragón-Vargas, L. F. (2014). Multilingual publication as a legitimate tool to increase access to science. Pensar En Movimiento: Revista de Ciencias Del Ejercicio y La Salud, 12(2), 10–17. https://doi.org/10.15517/pensarmov.v12i2.17584

Baldauf, R. B. (2001). Speaking of science: The use by Australian university science staff of language skills. In U. Ammon (Ed.), The dominance of English as a language of science: Effects on other languages and language communities (pp. 139–165). Mouton de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110869484.139

Bartholomäus, E., Goldbeck-Wood, S., Sewering, M., & Baethge, C. (2015). Experiences with bilingual publishing: Surveys of authors and editors. Learned Publishing, 28(4), 283–291. https://doi.org/1 0.1087/20150407

Bennett, K. (2013a). The translator as cultural mediator in research publication. In V. Matarese (Ed.), Supporting research writing: Roles and challenges in multilingual settings (pp. 93–106). Chandos. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-84334-666-1.50006-0

Bennett, K. (2013b). English as a Lingua Franca in academia: Combating epistemicide through translator training. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 7(2), 169–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509. 2013.10798850

Bocanegra-Valle, A. (2014). ‘English is my default academic language’: Voices from LSP scholars publishing in a multilingual journal. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 13, 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2013.10.010

Boéri, J. (2020). Activism. In M. Baker & G. Saldanha (Eds.), Routledge encyclopedia of translation studies (3rd ed., pp. 1–5). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315678627-1

Burgess, S., & Lillis, T. (2013). The contribution of language professionals to academic publication: Multiple roles to achieve common goals. In V. Matarese (Ed.), Supporting research writing: Roles and challenges in multilingual settings (pp. 1–15). Chandos. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-84334-666-1.50001-1

Burrough-Boenisch, J. (2019). Do freelance editors for academic and scientific researchers seek acknowledgement?: A cross-sectional study. European Science Editing, 45(2), 32–38. https://doi.org/10.20316/ese.2019.45.18019

Campbell, S. (2005). Chapter 2: English translation and linguistic hegemony in the global era. In G. Anderman & M. Rogers (Eds.), In and out of English: For better, for worse (pp. 27–38). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781853597893-005

Chan, L. T.-H. (2016). Beyond non-translation and “self-translation”: English as lingua academica in China. Translation and Interpreting Studies, 11(2), 152–176. https://doi.org/10.1075/tis.11.2.02cha

Cho, D. W. (2009). Science journal paper writing in an EFL context: The case of Korea. English for Specific Purposes, 28(4), 230–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2009.06.002

Cianflone, E. (2014). Communicating science in international English: Scholarly journals, publication praxis, language domain loss and benefits. Círculo de Lingüística Aplicada a la Comunicación, 57, 45–58. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_CLAC.2014.v57.44514

Connor, U. M. (1996). Contrastive rhetoric: Cross-cultural aspects of second language writing. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139524599

Di Bitetti, M. S., & Ferreras, J. A. (2016). Publish (in English) or perish: The effect on citation rate of using languages other than English in scientific publications. Ambio, 46(1), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0820-7

DiGiacomo, S. M. (2013). Giving authors a voice in another language through translation. In V. Matarese (Ed.), Supporting research writing: Roles and challenges in multilingual settings (pp. 107–119). Chandos. https://doi.org/10.1016/ B978-1-84334-666-1.50007-2

Donovan, S. K. (2009). A decline to nothing?: The tenuous existence of the small journal. Learned Publishing, 22(4), 323–324. https://doi.org/10.1087/20090410

Donovan, S. K. (2013). Death of a small journal? Journal of Scholarly Publishing, 44(3), 289–293. https://doi.org/10.3138/jsp.44.3.007

Duszak, A. (1997). Cross-cultural academic communication: A discourse-community view. In A. Duszak (Ed.), Culture and styles of academic discourse (pp. 11–39.). Mouton de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/ 9783110821048.11

Espinet, M., Izquierdo, M., & Garcia-Pujol, C. (2015). Can a Spanish science education journal become international?: The case of Enseñanza de las Ciencias. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 10, 1017–1031. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s11422-013-9545-0

Farley, A. F. (2018). NNES RAs: How ELF RAs inform literacy brokers and English for research publication instructors. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 33, 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2 018.02.002

Ferguson, G. (2013). English, development and education: Charting the tensions. In E. J. Erling & P. Seargeant (Eds.), English and development: Policy, pedagogy and globalization (pp. 21–44). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781847699473-005

Flowerdew, J. (2008). Scholarly writers who use English as an additional language: What can Goffman’s “stigma” tell us? Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 7(2), 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2008.03.002

Franco Aixelá, J. (2004). The study of technical and scientific translation: An examination of its historical development. The Journal of Specialised Translation, 1, 29–49. https://www.jostrans.org/issue01 /art_aixela.pdf

Fuentes, R., & Gómez Soler, I. (2017). Foreign language faculty’s appropriation of an academic publishing policy at a US university. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 39(3), 195–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2017.1344243

Gentil, G., & Séror, J. (2014). Canada has two official languages—Or does it?: Case studies of Canadian scholars’ language choices and practices in disseminating knowledge. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 13, 17–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2013.10.005

Getahun, D. A., Hammad, W., & Robinson-Pant, A. (2021). Academic writing for publication: Putting the ‘international’ into context. Research in Comparative and International Education, 16(2), 160–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/17454999211009346

Hempel, K. G. (2010). Übersetzen in den Geisteswissenschaften (Deutsch/Italienisch): Fachtexte der Klassischen Archäologie [Translation in the humanities (German/Italian): Specialist texts in classical archaeology]. In C. Heine & J. Engberg (Eds), Reconceptualizing LSP: Online proceedings of the XVII European LSP Symposium 2009 (pp. 1–13), Aarhus University. https://www.asb.dk/fileadmin/ www.asb.dk/isek/hempel.pdf

Hempel, K. G. (2011). Presente e futuro del plurilinguismo nelle scienze umanistiche. Il tedesco e l’italiano in archeologia classica [Present and future of multilingualism in the humanities. German and Italian in classical archaeology]. Lingue e Linguaggi, 6, 49–88. https://doi.org/10.1285/i2239-0359v6p49

Hoorickx-Raucq, I. (2005). Mediating the scientific text: A cultural approach to the discourse of science in some English and French publications and TV documentaries. The Journal of Specialised Translation, 3, 97–108. https://www.jostrans.org/issue03/art_hoorickx_raucq.pdf

Ibáñez-Martín, J. A. (2018). Las revistas de investigación como humus de la ciencia, donde crece el saber [Research journals as the topsoil where scientific knowledge grows]. Revista Española de Pedagogía, 76(271), 541–554. https://doi.org/10.22550/REP-3-2018-08

Jaspal, R. (2020). Content analysis, thematic analysis and discourse analysis. In G. M. Breakwell, D. B. Wright, & J. Barnett (Eds.), Research methods in psychology (5th ed., pp. 285–312). Sage.

Kanneh, K. (1997). Africa and cultural translation: Reading difference. In K. Ansell-Pearson, B. Parry, & J. Squires (Eds.), Cultural readings of imperialism: Edward said and the gravity of history (pp. 267–289). Lawrence & Wishart.

Kim, E.-Y. J. (2019). Korean scholars’ use of for-pay editors and perceptions of ethicality. Publications, 7(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications7010021

Kim, S., & Chesnut, M. (2016). Hidden lessons for developing journals: A case of North American academics publishing in South Korea. Journal of Scholarly Publishing, 47(3), 267–283. https://doi.org/10.3138/jsp.47.3.267

Klein, D. B., & Chiang, E. (2004). The Social Science Citation Index: A black box—with an ideological bias? Econ Journal Watch, 1(1), 134–165. http://econjwatch.org/316

Kuteeva, M. (2014). The parallel language use of Swedish and English: The question of ‘nativeness’ in university policies and practices. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 35(4), 332–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2013.874432

Kuteeva, M., & Mauranen, A. (2014). Writing for publication in multilingual contexts: An introduction to the special issue. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 13, 1–4. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jeap.2013.11.002

Leclerc, C. (2005). Between French and English, between ethnography and assimilation: Strategies for translating Moncton’s Acadian Vernacular. TTR: Traduction, Terminologie, Rédaction, 18(2), 161–192. https://doi.org/10.7202/015769ar

Li, X. (2018). What is the publication language in humanities? The case of Translation Studies scholars. English Today, 35(2), 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0266078418000202

Lillis, T., & Curry, M. J. (2006). Professional academic writing by multilingual scholars: Interactions with literacy brokers in the production of English-medium texts. Written Communication, 23(1), 3–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088305283754

López-Navarro, I., Moreno, A. I., Ángel Quintanilla, M., & Rey-Rocha, J. (2015). Why do I publish research articles in English instead of my own language?: Differences in Spanish researchers’ motivations across scientific domains. Scientometrics, 103(3), 939–976. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1570-1

Luo, N., & Hyland, K. (2019). “I won’t publish in Chinese now”: Publishing, translation and the non-English speaking academic. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 39, 37–47. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jeap.2019.03.003

Marais, K. (2018). Translation and development. In J. Evans & F. Fernandez (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of translation and politics (pp. 95–109). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315 621289-7

Martín Martín, P. (2003). A genre analysis of English and Spanish research paper abstracts in experimental social sciences. English for Specific Purposes, 22(1), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/ s0889-4906(01)00033-3

Mašić, I., Begić, E., Donev, D. M., Gajović, S., Gasparyan, A. Y., Jakovljević, M., Milošević, D. B., Sinanović, O., Sokolović, Š., Uzunović, S., & Zerem, E. (2016). Sarajevo declaration on integrity and visibility of scholarly publications. Croatian Medical Journal, 57(6), 527–529. https://doi.org/10.3325/cm j.2016.57.527

Mauranen, A. (1993). Cultural differences in academic rhetoric: A textlinguistic study. Peter Lang.

McGrath, L. (2014). Parallel language use in academic and outreach publication: A case study of policy and practice. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 13, 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2 013.10.008

McKenny, J., & Bennett, K. (2011). Polishing papers for publication: Palimpsests or procrustean beds?. In A. Frankenberg-Garcia, L. Flowerdew, & G. Aston (Eds.), New trends in corpora and language learning (pp. 247–262). Continuum. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474211925.ch-015

Moed, H. F., de Moya-Anegon, F., Guerrero-Bote, V., & Lopez-Illescas, C. (2020). Are nationally oriented journals indexed in Scopus becoming more international?: The effect of publication language and access modality. Journal of Informetrics, 14(2), 101011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2020. 101011

Mongeon, P., & Paul-Hus, A. (2016). The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics, 106, 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1765-5

Morley, G., & Kerans, M. E. (2013). Bilingual publication of academic journals: Motivations and practicalities. In V. Matarese (Ed.), Supporting research writing: Roles and challenges in multilingual settings (pp. 121–137). Chandos. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-84334-666-1.50008-4

Mur-Dueñas, P. (2013). Spanish scholars’ research article publishing process in English-medium journals: English used as a lingua franca? Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, 2(2), 315–340. https://doi.org/10.1515/jelf-2013-0017

Muresan, L.-M., & Pérez-Llantada, C. (2014). English for research publication and dissemination in bi-/multiliterate environments: The case of Romanian academics. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 13, 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2013.10.009

Ordorika, I. (2018). Las trampas de las publicaciones académicas [The academic publishing trap]. Revista Española de Pedagogía, 76(271), 463–480. https://doi.org/10.22550/REP-3-2018-04

Pérez-Rodríguez, M. A., García-Ruiz, R., & Aguaded, I. (2018). Comunicar: Calidad, visibilización e impacto [Communication: Quality, visibility and impact]. Revista Española de Pedagogía, 76(271), 481–498. https://doi.org/10.22550/REP-3-2018-05

Pisanski Peterlin, A. (2005). Text-organising metatext in research articles: An English–Slovene contrastive analysis. English for Specific Purposes, 24(3), 307–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.esp.2004.11.001

Pisanski Peterlin, A. (2008). Translating metadiscourse in research articles. Across Languages and Cultures, 9(2), 205–218. https://doi.org/10.1556/Acr.9.2008.2.3

Pisanski Peterlin, A. (2016). Engagement markers in translated academic text: Tracing translators’ interventions. English Text Construction, 9(2), 268–291. https://doi.org/10.1075/etc.9.2.03pis

Pisanski Peterlin, A. (2019). Self-translation of academic discourse: The attitudes and experiences of authors-translators. Perspectives, 27(6), 846–860. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2018. 1538255

Pulišelić, L., & Petrak, J. (2006). Is it enough to change the language?: A case study of Croatian biomedical journals. Learned Publishing, 19(4), 299–306. https://doi.org/10.1087/095315106778690733

Salager-Meyer, F. (2008). Scientific publishing in developing countries: Challenges for the future. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 7(2), 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2008.03.009

Salager-Meyer, F. (2014). Writing and publishing in peripheral scholarly journals: How to enhance the global influence of multilingual scholars? Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 13, 78–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2013.11.003

Salager-Meyer, F. (2015). Peripheral scholarly journals: From locality to globality. Ibérica, 30, 15–36. http://www.aelfe.org/documents/30_01_IBERICA.pdf

Schluer, J. (2014). Writing for publication in linguistics: Exploring niches of multilingual publishing among German linguists. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 16, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2014.06.001

Siepmann, D. (2006). Academic writing and culture: An overview of differences between English, French and German. Meta, 51(1), 131–150. https://doi.org/10.7202/012998ar

Sionis, C. (1995). Communication strategies in the writing of scientific research articles by non-native users of English. English for Specific Purposes, 14(2), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/0889-4906(95)00005-c

Uzuner, S. (2008). Multilingual scholars’ participation in core/global academic communities: A literature review. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 7(4), 250–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2008.10.007

Van Parijs, P. (2004). Europe’s linguistic challenge. European Journal of Sociology, 45(1), 113–154. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003975604001407

Warchał, K., & Zakrajewski, P. (2021). Multilingual publication practices in the social sciences and humanities at a Polish university: Choices and pressures. International Journal of Multilingualism. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2021.1966432

Wilmot, N. V., & Tietze, S. (2020). Englishization and the politics of translation. Critical Perspectives on International Business. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1108/cpoib-03-2020-0019

Xu, X., Oancea, A., & Rose, H. (2021). The impacts of incentives for international publications on research cultures in Chinese humanities and social sciences. Minerva, 59, 469–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-021-09441-w

Zheng, Y., & Gao, A. X. (2016). Chinese humanities and social sciences scholars’ language choices in international scholarly publishing: A ten-year survey. Journal of Scholarly Publishing, 48(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3138/jsp.48.1.1