What do codes of ethics tell us about impartiality, and what is preferred at the hospital?

Duygu Çurum Duman

Bilkent University

duygu.duman@bilkent.edu.tr

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3120-0577

Abstract

The impartiality of the interpreter has long been an important aspect of and an indispensable quality in healthcare interpreting. Official documents on professional ethics created by professional associations around the world refer to impartiality among the fundamental ethical principles to be adhered to. However, the conditions in the workplace and the background of the interpreter might pose significant risks to ensuring the implementation and adoption of ethics in the field. Furthermore, specific conditions of immigration and the quality (or the existence) of interpreter training in the required language combinations may play a role in either facilitating or impeding the implementation of ethical principles. As a country that has been receiving migrants for a relatively short time, Turkey lacks a code of ethics specifically drawn up for healthcare (or community) interpreters and this may well lead to problems in the field. Therefore, the primary objective of this study is to compare healthcare interpreters’ understanding of, preference for and exercise of impartiality with the prescripts of the codes applicable in other countries and to demonstrate how the principle of impartiality unfolds in healthcare contexts. The results of the study demonstrate that helping the patient was the main motivation of the interpreters in the field rather than being guided purely by impartiality. They reported being deliberately on the patient’s side to support them and to ensure that they obtained the required treatment, an approach which contradicts the codes of the associations in the countries that prefer “interpreting” rather than “mediation”. The analysis pointed to the fact that the meaning of impartiality is shaped by the system in which it is laid down. These results suggest that the codes and the attitudes of healthcare interpreters do not coincide as regards impartiality in a country where healthcare interpreting research and practice are emerging and training opportunities are scarce. They can serve as a useful reference point for policymaking and the professionalization of healthcare interpreters.

Keywords: healthcare interpreting, codes of ethics, impartiality, Turkey, hermeneutic phenomenological research.

1. Introduction

Codes of ethics perform the referential function of describing ethical rules and principles in a given profession and providing guidance to the people actively practising in the field. They encourage professionals to consider the ethical issues that may emerge during, before and following practice and to behave ethically when they arise (Phelan, 2020). These frameworks represent important milestones in setting the standards for the field concerned, especially in contributing to the process of professionalization. They are even considered a “hallmark of its professional status” (Setton & Prunč, 2015, p. 144). Even if the ethical principles are shared by the members of those associations that document the codes, their repercussions in practice might lead to various courses of action as interpreters make decisions about their conduct in their daily practice.

Research on codes of ethics in interpreting has demonstrated that some principles, such as preserving confidentiality and avoiding any conflict of interest, are universal, whereas others, such as impartiality, professional solidarity, clarifying interpreter roles and maintaining professional competence, have varying degrees of congruity (Bancroft, 2005). In a similar vein, Hale (2007) reported that the codes cover three broad areas of responsibility for the interpreter: to the authors of utterances, to the profession and to oneself as a professional. She also listed the principles included, from the most to the least frequent: confidentiality, accuracy, impartiality or conflict of interest, professional development, accountability or responsibility for own performance, role definition, professional solidarity and working conditions. Among these principles, accuracy, impartiality and confidentiality were affirmed as being the most common concepts in Rudvin’s research (2015). It is possible that these codes may not cover all the potential issues, nor will they offer solutions for every ethical conflict; however, they serve as an invaluable framework to adhere to before starting professional practice and they present an opportunity to consider the most frequent questions and to prepare responses to them.

These common principles raise the question of their applicability or practicability in the field. Both Hale (2007) and Rudvin (2015) suggest testing and verifying whether ethical principles do in fact match practice, or at least determining the extent to which principles and practice coincide. Indeed, Angelelli’s (2006) focus-group study with healthcare interpreters in California pointed to the need to revise prescriptive principles and to take the perspectives and feedback of interpreters into consideration, since the codes are not cast in stone. She states that “any attempt to prescribe what role interpreters should assume must take into consideration the situational reality of their working environments” (p. 189). Evolving conditions in the field and swiftly developing contexts necessitate a comprehensive and comparative discussion.

In contrast to these contexts where codes of ethics abound or cover many issues broadly, there are countries, such as Turkey, where healthcare interpreting services have been formalized relatively recently and the need to ensure the provision of these services came under the spotlight with the growth of mass migration. There is no doubt that translators and interpreters have remarkable associations that represent them – notably the Translators’ and Interpreters’ Association of Turkey (Ceviri Dernegi) and the Conference Interpreters’ Association of Turkey (Türkiye Konferans Tercümanları Dernegi), which prepared codes of professional ethics and conduct that target professionals at large. However, there are very few healthcare interpreters among the members of these associations and there are no codes of ethics that deal specifically with community interpreters in general, or even healthcare interpreters in particular. As an important step towards professionalization in this field, the Vocational Qualifications Authority (Mesleki Yeterlilik Kurumu), now serving under the Ministry of Labour and Social Security, issued the national occupational standards for translators and interpreters in 2013; and in line with that document, the “National Qualifications for Community Interpreters” has been drawn up in collaboration with professors from the Istanbul, Bogazici and Hacettepe universities. The document is currently being scrutinized by the authority and will come into effect upon ratification.[i] This document focuses on the skills and the competences required to perform different modes of interpreting. These modes will be tested, leading to accreditation in any of the six different settings of community interpreting: police/law enforcement, courtroom, healthcare, emergency and/or migration, sports and education. The evaluation of the theoretical and practical examinations for accreditation is explained in detail.

The context of healthcare has only recently enjoyed societal and governmental attention in Turkey. Healthcare interpreting courses are offered by a limited number of universities (Ross, 2018) at Bachelor’s level, and non-governmental organizations mostly offer short, in-house training courses for healthcare interpreters in the Arabic–Turkish language pair through state- or UN-funded projects. Within the scope of the most recent and ongoing project entitled “Improving the Health Status of the Syrian Population Under Temporary Protection and Related Services Provided by Turkish Authorities” or “SIHHAT”, healthcare interpreters (referred to as “patient guides”) were offered week-long professional training (see Toker, 2019). This training was reserved only for those “patient guides” selected to offer healthcare interpreting services for Syrians who are under temporary protection in Turkey. It covers the basics of medical terminology and effective verbal and non-verbal communication in healthcare, together with information on the healthcare system in Turkey. Healthcare interpreters working with language pairs other than Turkish–Arabic are not accommodated in this project. Simply put, training opportunities covering ethical issues are in the process of enhancement, and in this connection there is a growing need to understand how the ethical concerns are dealt with by healthcare interpreters in the field.

2. Impartiality

In its broadest sense, the neutrality of an interpreter can be understood as a quality in the relationship that they have with the interlocutors of an interpreter-mediated interaction (IMI). It refers to limiting or preventing any subjective considerations, beliefs or interests from having an impact on that interaction. Unlike linguistic neutrality, which refers to an objective style in language use, the interpreter’s neutrality is a principle of professional conduct that resurfaces particularly when there is a conflict of interest during an IMI (Zimanyi, 2009). Even though the ultimate shared aim of healthcare services is to ensure the patient’s well-being, conflicts of this sort may arise as the role expectations from an interpreter vary from one culture or profession to another (Angelelli, 2018; Crezee et al., 2020; Hsieh, 2006; Kainz et al., 2011). For this reason, it is a principle that occurs in many codes of professional ethics or conduct worldwide, which may vary in their comprehensiveness and in the exclusion of certain practices (Bancroft, 2005; Duman, 2018; Hale, 2007).

Because impartiality is the term generally preferred to neutrality in most codes of professional ethics (Prunč & Setton, 2015), it is preferred in this article. It refers to avoiding any conflict of interest or any advocacy of the rights of either party. Although there seems to be consensus on the need to refrain from any negative impact on the interaction, certain healthcare systems allow, and at times even promote, the prioritizing of the needs of the more vulnerable party (Duman, 2018). In other words, “neutrality” might as well mean “offering equal fidelity to all speakers” (Prunč & Setton, 2015, p. 273) while facilitating the process for the service user as an intercultural mediator in certain countries. This difference in perspective and emphasis has been considered previously in many national contexts (see Cox, 2015; De Boe, 2015; Safar & Hmami, 2014; Sauvêtre, 2000) and the role attributed to interpreters suggests the impact they have on the way in which impartiality is treated in the context in question.

As pointed out by Pöchhacker (2008), terminological preferences change according to the role assumed by the interpreter; the human agent in between may become a “mediator”, a “guide” or a “broker”. Unlike in the “pioneer states” (Leanza, 2008; Pöchhacker, 1999) that exerted great effort in providing training for interpreters in community settings and led the way globally towards the professionalization of the profession, the community interpreter becomes “language mediator” [mediatore linguistico] in Italy (Blini, 2008) and interpreter-mediator (interprète-médiateur) in France (Cohen-Emerique & Fayman, 2005). In Turkey, healthcare interpreters in community settings are officially referred to as “international patient experts” (Directive of Ministry of Health, 2013) and “patient guides” in the context of healthcare services for Syrian refugees. Consequently, it would be rational to assume that the concept of neutrality might be different in all these contexts.

Interpreters adopt certain attitudes and roles in order to ensure that communication proceeds seamlessly and therefore these various roles have been studied extensively all around the world, especially following the First Critical Link Conference, to consider whether all the typologies converge on certain continuums. For example, Brisset et al. (2013) use the terms of Habermas to describe each end of the role continuum and state that “interpreters oscillate between the Lifeworld and the System” so that communication can occur (p. 136). This pendulum metaphor is very convenient and illuminating while it also refers to the changes in interpreters’ positions along this continuum. More significantly, “[t]he more committed [interpreters] are to the patient, and the more empathy they express, the less neutral they will be” (Brisset et al., 2013, p. 136). Thus, we may infer that impartiality can be challenged by empathy in healthcare settings at different levels.

The impartiality of the healthcare interpreter has also been discussed from an “involvement” point of view. The conduit to the community embeddedness continuum suggested by Beltran-Avery (2011) points to the conceptualization of the interpreter as an embedded agent in her cultural–linguistic community, which in turn renders them an integral part of the community concerned. Beltran-Avery’s (2011) model was also endorsed in Angelelli’s (2019) neutral-to-active interpreter continuum. A further take on the neutrality of the interpreter is in the mental healthcare setting and it indicates an impartial-to-involved interpreter axis. This underlines the fact that interpreters may position themselves along this continuum depending on the conflict situation they are in during an IMI (Zimanyi, 2009). In brief, there is ample evidence that the impartiality of interpreters is not a fixed quality.

As an emerging context in healthcare interpreting services, Turkey has established a system that prioritizes the needs of the service user (Duman, 2018). In 2010, structural reorganization was introduced to boost the country’s medical tourism potential and improve the healthcare services available for other visitors and tourists. In addition, the “Health Tourism Department” was established, which currently serves under the Directorate General of Healthcare Services of the Ministry of Health. The outbreak of the Syrian civil war and the political unrest in the neighbouring regions had a great effect on this strategy, forcing additional measures to be implemented to provide healthcare to a larger non-Turkish-speaking community.

The reference to in-house healthcare (or hospital) interpreters as “guides” and “experts” in legislation in Turkey is an important indicator of a service that is closer to the cultural-mediation-oriented states (Pöchhacker, 2008). However, as discussed above, neutrality or impartiality is an important concept that may have different repercussions in each context. Therefore, looking into its framework in a new and unique context in comparison to the principles at play in other contexts is expected to shed light on the unfolding of the professionalization process in Turkey. The aim of this study is therefore to examine healthcare interpreters’ understanding of and preferences about impartiality in comparison to the available codes and to demonstrate how this principle unfolds in healthcare settings in Turkey.

3. Methodology

A hermeneutic–phenomenological approach was used for both the data-collection and their interpretation. An important objective of this approach is to understand or come to know the meaning and to make sense of an experience (Vandermause & Fleming, 2011). This approach requires the researcher to employ bracketing to examine the lived experiences as shared by the interviewee in their historical context. Bracketing – or setting aside and “suspending” researchers’ presuppositions about the concept in question while investigating experiences (Gearing, 2004) – is an essential part of the methodological approach preferred. It requires self-observation and the formulation of preconceptions, an awareness during research and the integration of the interviewee’s experience. It is also a prerequisite of understanding, since

conversation is a process of coming to an understanding. (…) What is to be grasped [in a conversation] is the substantive rightness of his opinion, so that we can be at one with each other on the subject. (Gadamer, 2013, p. 403)

For this reason, interviews were conducted in line with the Gadamerian (2013) concept of the Fusion of Horizons.

The first main concept of this study, the Fusion of Horizons, refers to the researcher’s openness to transformation to fully understand the interviewee. In the hermeneutic dialogue, understanding is a matter of coming to an agreement, or finding common ground, about the issue at hand. This agreement is basically establishing a common “horizon”. The fusion of horizons, therefore, corresponds to the level of understanding in which the researcher and the interpreter meet during the interview. To this end, the researcher asks questions in order to confirm their understanding of a matter. As a result of this circular dialogue and upon sharing their interpretation of the participant’s account, which was in turn shaped by the information and opinions conveyed by the participant, the researcher infers that the concept in question has evoked the same meaning for both parties.

The second main concept used was the Hermeneutic Circle. This refers to the process of understanding the issue under investigation from preconceptions of the meaning of its parts and their interrelationships (Willis, 2007). It also comes into play while conducting interviews and qualitatively analysing the interview data. The subcodes, codes and categories, and their relationships with each other and with the whole of the data, is constantly questioned; also, the context in which a specific code is assigned to a specific part of speech is taken into consideration. Eventually, the researcher's interpretation is shaped by the continuity of this circle.

4. Data-collection

In this section, a brief overview is presented of the data-collection process of this study. The collected data are composed of two main parts, resulting in two data sets, all of which were coded and analysed thematically on MaxQDA 11 software.

4.1 Data set 1: Codes of ethics

The first part of this study includes a thematic analysis of purposefully selected codes of ethics from different countries and associations. To understand how the concept of neutrality or impartiality unfolds in these documents, we started with a pre-selected set of 19 documents compiled by FIT Europe, the Regional Centre of the International Federation of Translators. FIT Europe compiled codes from its member associations for a project carried out between 2005 and 2009 to create a common code of professional ethics for the region (FIT Europe, 2017). The documents constituting the first part of Data set 1 are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. First group of codes of ethics selected by FIT Europe

|

# |

Source |

Name of document |

Primary audience |

|

1 |

FIT Europe |

Code of Professional Practice |

Translators/Interpreters |

|

2 |

Sweden |

Code of Professional Conduct – The Swedish Association of Professional Translators |

Translators/Interpreters |

|

3 |

UK |

Code of Professional Conduct (individual members) – Institute of Translation & Interpreting (ITI) |

Translators/Interpreters |

|

4 |

Switzerland 1 |

Code de déontologie de l’Association suisse des traducteurs, terminologues et interprètes |

Translators/Interpreters |

|

5 |

Chechia |

Jednota tlumočníkůa překladatelů |

Translators/Interpreters |

|

6 |

Poland |

Code du traducteur assermenté de l’Association Polonaise des Traducteurs Economiques, Juridiques et Judiciaires (TEPIS) |

Sworn-in Economy and Law Translators |

|

7 |

Netherlands |

Netherlands Association of Interpreters and Translators (NGTV) Code of Honour |

Translators/Interpreters |

|

8 |

Germany |

Berufs- und Ehrenordnung (Grundsätze des Standesrechts) 8a. ADÜ Nord (Assoziierte Dolmetscher und Übersetzer in Norddeutschland e.V.) 8b. ATICOM (Fachverband der Berufsübersetzer und Berufsdolmetscher e.V.) 8c. VÜD (Verband der Übersetzer und Dolmetscher e.V.) 8d. BDÜ (Bundesverband der Dolmetscher und Übersetzer e.V.) |

Translators/Interpreters |

|

9 |

Austria |

Berufs- und Ehrenordnung – UNIVERSITAS: Der österreichische Berufsverband für Dolmetschen und Übersetzen |

Translators/Interpreters |

|

10 |

Belgium 1 |

Code de déontologie de la CBTI (Chambre belge des traducteurs et interprètes) |

Translators/Interpreters |

|

11 |

Denmark |

Code of Ethics – Danish Association of State-authorised Translators and Interpreters |

Translators/Interpreters |

|

12 |

France 1 |

Charte du Traducteur – Société française des traducteurs professionnels |

Translators/Interpreters |

|

13a |

Ireland 1 |

Code of Practice and Professional Ethics – Irish Translators’ and Interpreters’ Association (ITIA) |

Translators/Interpreters |

|

13b |

Ireland 2 |

ITIA Code of Ethics for Community Interpreters |

Community Interpreters |

|

14 |

Italy |

Codice Deontologico – Associazione Italiana Traduttori e Interpreti |

Translators/Interpreters |

|

15 |

Greece |

Code of Ethics of the Panhellenic Association of Professional Translators Graduates of the Ionian University (PEEMPIP) |

Translators/Interpreters |

Upon completing the first phase of thematic analysis, the emphasis on impartiality as a concept that varies according to the primary target audience became observable to a limited extent. However, this analysis revealed that these documents focused only on impartiality among other principles and from a broader perspective and did not provide sufficient insight into the concept in question. For a closer view and a comparison, I decided to run a second thematic analysis on another group of 11 documents that are concerned exclusively with community or healthcare interpreters. In Table 2, the second group of codes is listed with the objective of representing both the codes from the states that are pioneering the professionalization of community interpreting in their settings and highlighting the “interpreting practice” of the community or healthcare interpreter’s role that is relatively closer to the conduit model, on the one hand, and those from the states in which a cultural mediation role is more prevalent (Pöchhacker, 2008), on the other. The codes from Australia, Canada and the United States represent the former system; those from France, Belgium and Switzerland, where the “mediator” role is more prevalent, represent the latter. Here, it should also be underlined that in the United States, the California Healthcare Interpreters Association (CHIA) has its own guidelines which are presented in detail in a document entitled “California Standards for Healthcare Interpreters: Ethical Principles, Protocols, and Guidance on Roles and Intervention” (2002). In these guidelines four roles of interpreters are defined: message converter, message clarifier, cultural clarifier and patient advocate. The potential risks and benefits of these roles are explained in these standards and the fact that interpreters may shift from one role to the other during the same assignment is acknowledged.

The code of the US-based International Medical Interpreters Association (IMIA) and a local code issued by Ceviri Dernegi (ÇD) were also included in order to present a broader perspective on neutrality and impartiality. Even though the ÇD code of ethics does not focus solely on community interpreters and their professional conduct, this association also represents community interpreters in Turkey, very few of whom prefer to adhere to an association. This document was selected to represent the Turkish case.

Table 2. Second group of codes of ethics

|

# |

Source |

Name of document |

Primary audience |

|

1a |

Australia 1 |

AUSIT Code of Ethics and Code of Conduct |

Translators/Interpreters |

|

1b |

Australia 2 |

NSW Health Care Interpreting Services – Guidelines for Interpreters |

Healthcare Interpreters |

|

2a |

Canada 1 |

Code de déontologie de l’Ordre des traducteurs, terminologues et interprètes agréés du Québec |

Translators/Interpreters and Terminologist |

|

2b |

Canada 2 |

National Standard Guide for Community Interpreting Services |

Community Interpreters |

|

3a |

USA 1 |

Code of Ethics and Professional Practice – American Translators Association (ATA) |

Translators/Interpreters |

|

3b |

USA 2 |

A National Code of Ethics for Interpreters in Health Care – National Council on Interpreting in Health Care |

Healthcare Interpreters |

|

4 |

France 2

|

Charte de l’interprétariat médical et social professionnel en France |

Community and Healthcare Interpreters |

|

5 |

Switzerland 2 |

Code professionnel des interprètes communautaires et des médiateurs/trices interculturel-le-s – INTERPRET |

Community Interpreters and Intercultural Mediators |

|

6 |

Belgium 2 |

Code de déontologie de l’interprète en milieu social – SeTIS-Bxl |

Community Interpreters |

|

7 |

IMIA |

Code of Ethics for Medical Interpreters |

Healthcare Interpreters |

|

8 |

Turkey |

Mesleki ve Etik İlkeler Bildirgesi – Translation and Interpreting Association of Turkey |

Translators/Interpreters |

4.2 Data set 2: Interviews

The second part of the study is composed of interviews with 27 healthcare interpreters on impartiality. The data used for this study constitute part of a larger corpus of interviews developed within the scope of my doctoral research. The interviews were semi-structured, yet the fundamental questions were used only as anchors; they were asked to all the participants, and some of the participants preferred to dwell more upon certain questions than others, which led to more follow-up questions, a more detailed conversation and, finally, to a fusion of horizons between the researcher and the participant. The participants comprised 27 healthcare interpreters (13 male and 14 female) working at public (no. = 1) and private (no. = 6) hospitals in Istanbul, Turkey.

The data-collection process started in March 2016 and ended in November 2017. At the outset, the interviewees were selected on the basis of purposive sampling and later snowball sampling. Healthcare interpreters employed by two A-level hospitals in Istanbul were approached and those who gave their consent for voice recording were selected. Later, the administrators of one hospital and the participants of the latter referred the researcher to other interpreters working at other hospitals in the same province. The researcher’s colleagues also provided the telephone numbers of some interpreters, who later contacted other interpreters who were willing to participate in the study.

Of the 27 participants in this study, 13 were working with the Arabic–Turkish language pair. The second most frequent language pair was Russian–Turkish (8 interpreters); 21 participants (75%) were citizens of a state other than Turkey and the majority of them (17 participants) reported that they had learned Turkish as a foreign language after they had immigrated. Only one participant had Turkish as their only mother tongue. The rest of the participants were raised bilingually. Some 22 participants (81% of the total number) had either high school or a Bachelor’s degree and 5 participants (19%) were still undergraduate students during the data-collection process. Only 3 participants were graduates of a Translation and Interpreting Studies (TIS) programme in Turkey or abroad. Except for 1 participant, who was among the TIS graduates, all the participants reported that they had never received any training in interpreting in healthcare settings.

In Turkey, interpreters working exclusively in healthcare settings are not recruited by the patients; they are employed by individual hospitals (public or private) instead, and the service is offered free of charge in any healthcare institution. Therefore, the daily wage or monthly salary of interpreters is paid by the institution. Of course, ad hoc interpreters, such as the neighbours or the children of the patients, may accompany them to the hospital, but they do not directly make contact with the interpreters of the healthcare institutions and recruit them for assignments.

5. Findings and discussion

5.1 Impartiality in codes of ethics

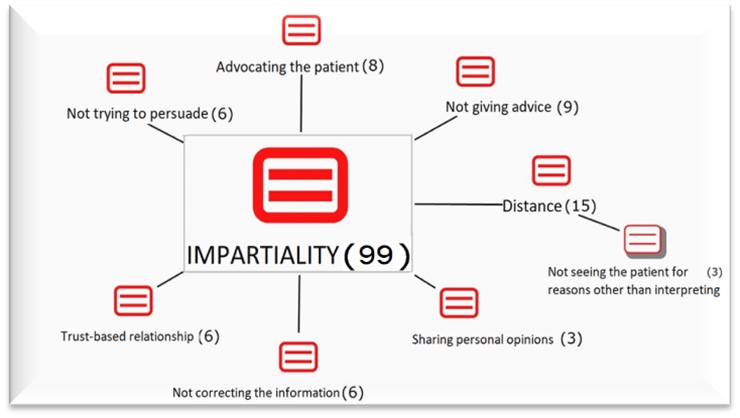

The conceptual content of neutrality and the interchangeably used impartiality in the documents analysed, as demonstrated in Figure 1, concentrate mainly on behavioural restrictions. The codes and subcodes attributed during qualitative thematic analysis to the segments of the documents concerned suggest that refraining from persuading the patient, giving advice, and correcting the information that an interlocutor gives are significant steps towards achieving impartiality. Sharing personal opinions, being on the patient’s side or being the patient’s advocate are discussed mainly in the second group of codes. Forming a relationship based on trust and the distance to be maintained vis-à-vis the patient are also included in the second group.

Overall, the concept of impartiality as an interpersonal quality is represented as a prescriptive perspective regarding certain actions, namely:

· refraining from affecting the relationship of the parties and “taking a step back” so that the interpreter can bracket their own migration experience, if any, to ensure that this experience does not interfere in the performance (Belgium-SeTIS-BXL);

· avoiding representing anyone (Poland 2);

· refraining from “emphasizing” or “softening” statements (Australia – AUSIT), and

· ensuring that one declares any relationship of interest that may affect their impartiality (UK).

Figure 1. Impartiality categories and distribution

of the researcher’s codes and sub-codes attributed to segments of the first

data set

A comparison of the codes used for the documents listed in Table 2 pointed to yet another continuum: from impartiality to multipartiality. As previously indicated, impartiality is rather strictly adhered to in the codes from the pioneer states, whereas the codes from the countries with an intercultural mediation background point at the importance of taking the side of both parties, in such a way that there’s an equality in the improvement of mutual understanding for both of them. The AUSIT code of ethics (2012) emphasises that interpreters are bound by impartiality and that they must not “allow bias to influence their performance” (p. 11). And in instances where a risk of impartiality arises because of personal experience or beliefs, the code suggests that the interpreter withdraw from the assignment.

The code of INTERPRET from Switzerland (2015), on the other hand, underscores “a multi-partial attitude” and “keeping the same professional distance with each interlocutor” (p. 1). Since being on the patient’s side rarely affects the rights and interests of the healthcare professional in a healthcare setting, where the ultimate objective is to restore or preserve the patient’s physical and mental well-being, multipartiality might be interpreted as an option to take the patient’s side unless it causes harm to the other party. It is important that interpreters and mediators represent the parties with the utmost autonomy possible.

The thematic analysis of the codes also revealed a parallel result to, inter alia, Zimanyi’s (2009) research, which suggests that much importance is attached to advocacy and assistance to the service user in some contexts, such as South Africa, while the Canadian, Australian, Irish, Finnish, Dutch, Swedish and Danish professional associations adopt a more or less standard approach in their adherence to impartiality. In brief, neutrality and impartiality can be experienced to varying intensities in line with the country, context, type of interpreter and their roles.

5.2 Impartiality in hospital: Interviews

In this section, the results of the previous thematic analysis will be compared to the thematic analysis of the interviews and, within the scope of this article, the sub-themes raised will be limited to “Persuasion”, “Giving advice”, and “Distance”. Somewhat surprisingly, the thematic analysis of the interviews revealed that the term “neutrality” or “impartiality” (in Turkish: tarafsizlik for both terms) is very seldom referred to by the participants; yet the sub-themes abound with the conceptual components of impartiality discussed above. As shown in Table 3, the frequency of directly expressed ethical concerns related to impartiality was five percent in the overall interview data. In the rest of the data, “Persuasion”, “Giving advice”, “Distance”, “Trust”, “Empathy” and “Decision-making” appear as emerging sub-themes. The accounts of the participants point to the fact that neutrality or impartiality is not their primary concern; instead, the interviewees’ main motivation in this study was “helping” the patient, and empathy is the main reason the participants gave for considering helping to be indispensable.

Table 3. Frequency of the codes that express an ethical concern about impartiality

|

Code |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Ethical concern |

18 |

5.26 |

|

Interpreting process |

324 |

94.74 |

|

Total |

342 |

100.00 |

Only three of the 27 interpreters (11%) openly referred to being neutral or impartial. One of them, Interpreter #6–2,[ii] had graduated from a school of medical sciences in Syria but had not yet started working as a nurse; he learned Turkish upon arrival in the country. At the time of data-collection, he had been working as a healthcare interpreter in Turkey for the past four years. He was very clear on the need for impartiality throughout an interview, stating:

[I]n my opinion, [the interpreter] should remain impartial with the patient and himself, with the patient and the doctor. His duty shall only be this: I brought this patient to the doctor. I’ll explain his problem. I’ll interpret what [the doctor] says to the patient. He should not take sides (Interpreter#6–2).

When he had to deliver sensitive information, however, Interpreter #6–2 explained that he preferred paraphrasing the information by using a softer register so that the patient would not be negatively affected by the nuances of meaning of certain information and phrases:

No, I’m impartial. I’m impartial. Doctor speaks, I interpret the same thing. But sometimes, for example, when he says something directly in Turkish, and when I interpret it directly into Arabic, it is as if [the patient] was slapped. [It sounds abrupt.] What do I do with that? I soften the words. I use different words, but the meaning remains the same. Its essential meaning, I mean. I try to tell it differently, softer (Interpreter#6–2).

As expected, the AUSIT code of ethics (2012) clearly disallows such a preference by stating that “[translators/interpreters] do not soften, strengthen or alter the messages being conveyed” (p. 5). Since Interpreter #6–2 had a medical background, he had experienced delivering bad news during professional training courses and he put this background into use while interpreting. He reported managing the information flow and deliberately “using a softer tone of voice” based on his experience as a nurse-intern. He referred to medical ethics while making ethical decisions during interpreting. Nevertheless, it might be useful to underline that clinical staff do not receive standard in-house training on how to work with interpreters. Therefore, the relationship between clinical staff and foreign patients during multilingual and multicultural communication might, at times, require the interpreter to act as an emotional regulator.

Another Interpreter, #6–1 referred to neutrality as impartiality, emphasizing conflict of interest; he stated that “we, ourselves should be neutral but we work at a hospital. We also need to protect the institution, and patients’ rights at the same time.” However, he also shared a bitter experience with a patient whose insurance plan was cancelled during treatment, an experience that in retrospect became a comforting memory for him. He reported having talked to the doctor who had operated on that patient and persuading him to dress the patient’s wound pro bono at the insistence of the patient. This is a clear example of side-taking; however, the patient was in a very dire situation and this action helped him recover from an otherwise irreversible condition. In this case, no harm was caused to the healthcare system since the doctor had the option to accept or reject performing the dressing free of charge; and the decision resulted in a greater good.

Similarly, Interpreter #5–3 indicated that there is a “[…] need to empathize with [the patient], first of all”. But managing the boundaries of empathic behaviour is crucial and remains obscure in this example. “You need to be constantly in contact with the doctor,” she reported, since the patients she was interpreting for asked questions about the treatment and the rehabilitation process all the time. For this reason, she stated that they “call the doctors, over and over again, disturbing them. Just so that the patients felt relieved.” Here, I should stress that interpreting services are free of charge in both public and private hospitals in Turkey and that bilateral agreements exist between the ministries of health, ensuring free treatment for a fixed number of patients each year. Therefore, even though patient satisfaction is an important consideration, it should be borne in mind that the majority of the patients coming from a number of countries to Turkey are not medical tourists but refugees. Yet, in this example, empathy and the motivation to console the patients are the factors that determine the level of impartiality or the lack of it.

5.2.1 Persuasion

Respecting the autonomy of the patient is an important component of both impartiality and multipartiality (multipartialité). Both the National Code of Ethics for Interpreters in Health Care from the United States, and the SeTIS BXL code from Belgium underline the right of the patient to make decisions for themselves. “[T]herefore, interpreters should not take sides or attempt to persuade either party” (NCIHC, 2004, p. 16). Even though there is a consensus on both groups in this respect, Interpreter #7–1 raises an important question here. He was responsible for interpreting only for Syrians under temporary protection, and also helped the hospital staff during pre-natal information-sharing sessions. For this reason, he considered informing the patients he interpreted for outside the class as well. He indicated that:

If you have experience in a job, if you have knowledge – the knowledge of that – for example, if a newborn is in a condition [of jaundice] that requires remaining, in the hospital, you may have to persuade the patient to stay, even without talking about it to the doctor. Me, for example, I do that by taking initiative, alright. It might be wrong; it might be right. Well, I consider that completely to be a humanitarian duty, a conscientious one. When I do that, it brings about [positive] results and that makes me happier, since I obtained results in all of my attempts until now (Interpreter #7–1).

Interpreter #7–1 reported several other cases when he persuaded the patients, mainly migrants of a lower educational background, to receive or continue receiving treatment when there were fatal risks involved. He based this preference on lack of thorough knowledge on the condition and undertook the duty of informing the patients further especially while interpreting consent forms that patients sign to be discharged from the hospital or discontinuing a specific treatment. It is clear that patient autonomy is crucial provided that the patient is fully informed about the consequences of the preferred course of action. In these examples, we understand that the interpreter considers saving lives and preventing further suffering valuable and prefers to take the time to make detailed explanations and informing the patients further than what might be necessary, which is also completely against the principle of impartiality as described in the abovementioned codes. However, life-threatening risks might also be considered sufficient for “[a]dvocating the patient (…) only when the health and well-being of the patient is at risk” (NCIHC, 2004, p. 20).

5.2.2 Giving advice

Offering advice or personal opinions is among the activities to avoid for the sake of maintaining impartiality. This is explicitly stated in many codes of ethics that target both the general audience of translators and interpreters and community or healthcare interpreters (see, among others, IMIA; AUSIT; Ireland 2). However, reminding or advising the patient to share prior knowledge with the healthcare professional has been reported by the interviewees. For example, Interpreter #6–3 shared that he encouraged patients at times to give specific information to the doctor that otherwise would have remained untold. He stated:

Sometimes we remind the patient when he enters the doctor’s office. We say, “you were going to say that; would you like to talk about it to the doctor now?” He himself will not share that information, out of hesitation. I convince him to share that information. The doctor knows better (Interpreter #6–3).

Interpreter #6–3 was convinced that these were very minor interventions, yet through them “the patient [talked] about [that information] outside” the doctor’s rooms. Since interpreters mostly accompany patients in private hospitals in Turkey, they tend to wait, for example, with the patient before and after their appointment or while they wait to receive their lab results, if it is for a short period of time. Therefore, they generally talk and share information while having an ordinary chat.

Another Interpreter, #1–7, reported very casually that she used to remind the patients to tell the doctor specific information that she was told before the appointment. “Sometimes, patients explain something to me, but forget about it completely when they enter the doctor’s office. At that point, I say, erm, ‘you forgot to tell this and that’, for example.” She also added insistently that she only interpreted what the parties to the encounter said to one another. Clearly, reminding a patient about important details is for the benefit of the patient and causes no harm to any party; it is also quite different from advising a patient to follow certain courses of action. However, the Canadian code is strictly against such conversations, indicating that “[t]he interpreter avoids unnecessary contact with the parties” (HIN, 2007, p. 27). In addition, Hale (2007) suggests avoiding being alone with a patient, among other reasons, in order to maintain impartiality – although she does add that the code covers only the encounter itself, not any encounters outside of it. Nevertheless, it might be an important aspect to keep in mind while dealing with certain initiatives. Owing to their job description, healthcare interpreters are generally required to accompany the patient in the premises, which clearly results in their being alone and having casual conversations.

5.2.3 Distance

Finally, we touch on maintaining boundaries or distance, which is one of the most frequently raised components of impartiality in the codes from both traditions. Interestingly, rather than the concept of distance, we observed that of “closeness” in the interview data. Nearly all the participants reported considering positively having a friendly relationship with the patients they were interpreting for. However, being on good terms with the patients might not always turn out to be easy to manage. Interpreter #4–1 states that:

They are very serious cases, and they require constant monitoring. Naturally, when the patient can’t reach me from my work number, I may be obliged to give them my personal mobile number. […] Consequently, sometimes they call in the middle of the night, at 12 [am]. Sometimes at 11 [pm]. In the end, the patient is in question, and I think like that: She could have been my mother. Or he could have been my father, or my brother, and I treat the patients this way (Interpreter #4–1).

In this case, over-empathetic decision-making clearly forced Interpreter #4–1 to challenge their professional and personal boundaries, which had a detrimental effect on her work–life balance. However, some interviewees focused on the greater good and reported cases where they behaved extremely sincerely towards the patients. For example, Interpreter #2–4 stated that “[t]reating the patient as if s/he is [her] mother or father, trying to be close, understanding him/her [is important]”. In her experience as an interpreter, being tolerant and understanding is a quality that yielded “better results”. She also reported keeping in contact with the patients, thanks to an online text-messaging app, even after the assignment was over and the patients returned to their country of residence.

Like #2–4, Interpreter #6–4 worked with a language of limited diffusion, or with a language whose population of speakers is relatively small in a geographic area. In this case, being a member of a community came to the fore and rendered the sense of belonging more observable in the interpreter’s discourse. Loyalty, as a value, creates social cohesion and trust; and confidentiality and impartiality force us to “protect and restrain that very nature of loyalty that we might feel towards one or more parties” (Rudvin, 2020, pp. 55–57). Interpreter #6–4 indicated that helping one another was an important asset in his community and in his country of origin, and he accompanied the patients even on Sundays, if need be. Sharing a language and being abroad together strengthens the ties, sometimes to the detriment of the interpreter, while giving them a sense of accomplishment by helping their “people” (Interpreter #2–2) in any way that was within their power.

But Hale (2007) cautions that “making a conscious effort to remain impartial can help avoid emotional involvement and possible burn-out” (p. 122). Indeed, a lack of professional distance or emotional detachment might seriously affect the interpreter’s capacity to sustain these services. For that, the boundaries of the notion should be discussed in detail at least during in-house training sessions. Organizing such sessions alone might be a considerable contribution to professionalization.

6. Conclusion

It can be argued that “medical interpreters should be held to a different standard than their counterparts in legal settings, given the collaborative nature of most healthcare interactions” (Mikkelson, 2008, p. 85). Indeed, this study was born out of an effort to demonstrate the peculiarities of ethical standards of impartiality in healthcare interpreting. The accounts of the participants from Turkey illustrated that neutrality or impartiality was not their primary concern; helping the patient with empathy was their main motivation. Many interviewees reported being deliberately on the patient’s side to support and ensure treatment, which contradicts the codes of countries that emphasise the “interpreting” role rather than that of “mediation”. According to Angelelli (2006), “[a]lthough their position might be viewed as a violation of [impartiality], they seem to feel that their role in preventing misunderstandings, which are often due to cultural differences, overrides it” (p. 183). Their role definition that resulted from their duties and responsibilities (e.g., expert; patient guide) poses a challenge to the need for impartiality. Considering the interview data, we might infer that the participants in this study, although only a fraction of the healthcare interpreters in Turkey, were closer to the involvement (Zimanyi, 2009), Lebenswelt (Brisset et al., 2013) or active interpreter pole in the continuum from impartial to multipartial (Angelelli, 2019).

In conclusion, there is a considerable lack of coincidence between the codes of ethics around the world and the preferences of the group of interpreters interviewed about impartiality. These results may serve as a reference point for professionalizing the field in Turkey and the specific conditions of the healthcare context should be taken into consideration for the purposes of policymaking. The current position regarding ethical concerns seems to be beneficial to patients. However, this clearly places an emotional burden on the shoulders of healthcare interpreters, their highly empathetic relationships rendering them psychologically vulnerable. Consequently, offering support mechanisms and periodic supervision in order to bolster interpreters is of the utmost importance. For this reason, drawing up context-specific regulations and codes of ethics, informed by fieldwork rather than general principles, and raising awareness about such regulations and codes, would be valuable contributions to the position of interpreters in the healthcare system.

References

Angelelli, C. V. (2006). Validating professional standards and codes: Challenges and opportunities. Interpreting, 8(2), 175–193. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.8.2.04ang

Angelelli, C. V. (2018). Who is talking now? Role expectations and role materializations in interpreter-mediated healthcare encounters. Communication and Medicine, 15(2), 123–134. https://doi.org/10.1558/cam.38679

Angelelli, C. V. (2019). Healthcare interpreting explained. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315310978

Bancroft, M. (2005). The interpreter’s world tour: An environmental scan of standards of practice for interpreters. The California Endowment.

Beltran-Avery, M. P. (2011). The role of the healthcare interpreter: An evolving dialogue. https://www.ncihc.org/assets/documents/workingpapers/NCIHC%20Working%20Paper%20-%20Role%20of%20the%20Health%20Care%20Interpreter.doc

Blini, L. (2008) Mediazione linguistica: Riflessioni su una denominazione. Rivista Internazionale di Tecnica della Traduzione, 10, 123–138.

Brisset, C., Leanza, Y., & Laforest, K. (2013). Working with interpreters in health care: A systematic review and meta-ethnography of qualitative studies. Patient Education and Counseling, 91(2), 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.11.008

California Healthcare Interpreters Association. (2002). California standards for healthcare interpreters: Ethical principles, protocols, and guidance on roles & intervention. https://www.chiaonline.org/resources/Pictures/CHIA_standards_manual_%20March%202017.pdf

Cohen-Emerique, M., & Fayman, S. (2005). Médiateurs interculturels, passerelles d'identités. Connexions, 83(1), 169–190. https://doi.org/10.3917/cnx.083.0169

Cox, A. (2015). Do you get the message?: Defining the interpreter’s role in medical interpreting in Belgium. MonTI: Monografías de Traducción e Interpretación, 2, 161–184. https://doi.org/10.6035/MonTI.2015.ne2.6

Crezee, I., Zucchi, E., & Jülich, S. (2020). Getting their wires crossed?: Interpreters and clinicians’ expectations of the role of professional interpreters in the Australian health context. New Voices in Translation Studies, 23, 1–30.

De Boe, E. (2015). The influence of governmental policy on public service interpreting in the Netherlands. The International Journal for Translation & Interpreting Research, 7(3), 166–184. https://doi.org/10.12807/ti.107203.2015.a12

Directive of Ministry of Health (2013). 23.07.2013 tarihli ve 25541 sayılı Bakan Onayı ile yürürlüğe konulan Sağlik turizmi ve turist sağliği kapsaminda sunulacak sağlik hizmetleri hakkinda yönerge [Directive on healthcare services in the scope of medical tourism and tourist health issued upon Ministerial Approval no. 25541, dated 23 July 2013]. https://www.saglik.gov.tr/TR,11286/saglik-turizmi-ve-turist-sagligi-kapsaminda-sunulacak-saglik-hizmetleri-hakkinda-yonerge.html

Duman, D. (2018). Toplum çevirmenliğine yorumbilgisel yaklaşım: Sağlık çevirmeni ve öznellik [A hermeneutic approach to community interpreting: Healthcare interpreter and subjectivity]. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Yıldız Technical University.

Gadamer, H. G. (2013). Truth and method. J. Weinsheimer & D. G. Marshall (Translated into English. Original Wahrheit und Methode, 1975; 1989; 2nd ed. 2004). Bloomsbury.

Gearing, R. E. (2004). Bracketing in research: A typology. Qualitative Health Research, 14(10), 1429–1452. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732304270394

Hale, S. (2007). Community interpreting. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230593442

Hsieh, E. (2006). Conflicts in how interpreters manage their roles in provider–patient interactions. Social Science & Medicine, 62, 721–730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.029

Kainz, C., Prunč, E., & Schögler, R. (2011). Modelling the field of community interpreting: Questions of methodology in research and training. Lit.

Leanza, Y. (2008). Community interpreter’s power: The hazards of a disturbing attribute. Curare, 31(2–3), 211–220.

Mikkelson, H. (2008). Evolving views on the court interpreter’s role. In C. Valero-Garcés & A. Martin (Eds.), Crossing borders in community interpreting (pp. 81–97). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.76.05mik

Pöchhacker, F. (1999). Getting organized: The evolution of community interpreting. Interpreting, 4(1), 125–140. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.4.1.11poc

Pöchhacker, F. (2008). Interpreting as mediation. In C. Valero-Garcés & A. Martin (Eds.), Crossing borders in community interpreting: Definitions and dilemmas (pp. 9–26). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.76.02poc

Phelan, M. (2020). Codes of ethics. In M. Phelan, M. Rudvin, H. Skaaden, & P. S. Kermit (Eds.), Ethics in public service interpreting (pp. 85–146). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315715056-3

Prunč, E., & Setton, R. (2015). Neutrality. In F. Pöchhacker (Ed.), Routledge encyclopedia of interpreting studies (pp. 273–276). Routledge.

Ross, J. M. (2018). Toplum çevirmenliği eğitimi: Çeviri pratiği, yerel gerçekler, uluslararası uygulamalar ve araştırmanın önemi [Community ınterpreter training: Interpreting practice, local facts, ınternational practices, and significance of research]. In E. Diriker (Ed.), Türkiye’de sözlü çeviri eğitimi, uygulamaları ve araştırmaları [Training, practice and research on ınterpreting in Turkey] (pp. 283–312). Scala.

Rudvin, M. (2015). Etica, filosofia e mediazione linguistica: Dall’etica della filosofia al codice deontologico della mediazione lingüistica. Lingue Linguaggi, 16, 393–412.

Rudvin, M. (2020). Situating interpreting ethics in moral philosophy. In M. Phelan, M. Rudvin, H. Skaaden, & P. S. Kermit (Eds.), Ethics in public service interpreting (pp. 24–84). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315715056-2

Safar, H., & Hmami, A. (2014). L’interprétation en milieu social, profil et mission en Belgique francophone. Monografías de çédille, 4, 77–89.

Sauvêtre, M. (2000). De l’interprétariat au dialogue à trois : Pratiques européennes de l’interprétariat en milieu social. In R. Roberts, S. Carr, D. Abraham, & A. Dufour (Eds.), The Critical Link 2: Interpreters in the community (pp. 35–44). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.31.05sau

Setton, R., & Prunč, E. (2015). Ethics. In F. Pöchhacker (Ed.), Routledge encyclopedia of interpreting studies (pp. 144–148). Routledge.

Toker, S. S. (2019). Evaluation of adaptation training provided by the ministry of health and the world health organization: patient guides within the context of healthcare interpreting training in Turkey [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Hacettepe University.

Vandermause, R. K., & Fleming, S. E. (2011). Philosophical hermeneutic interviewing. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 10(4), 367–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691101000405

Willis, J. (2007). Foundations of qualitative research: Interpretive and critical approaches. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452230108

Zimanyi, K. (2009). On impartiality and neutrality: A diagrammatic tool as a visual aid. The International Journal of Translation and Interpreting Research, 1(2), 55–69.

Web Sources for Codes of Ethics

Australia 1 AUSIT. (2012). AUSIT code of ethics and code of conduct. https://ausit.org/AUSIT/Documents/Code_Of_Ethics_Full.pdf

Australia 2 NSW. (2017). Health care interpreting services: Guidelines for interpreters. https://www.wslhd.health.nsw.gov.au/ArticleDocuments/518/HCIS Brochure.pdf.aspx

Austria UNIVERSITAS. (2017). Österreich Berufs- und Ehrenordnung. http://www.fit-europe.org/vault/ber-universitas.html

Belgium 1. (2017). Code de déontologie de la chambre belge des traducteurs, interprètes et philologues. http://www.fit-europe.org/vault/deontologie-cbitp.html

Belgium 2. SeTIS BXL. (2017). Code de déontologie de l’interprète en milieu social. http://www.setisbxl.be/wp/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Code-de-déontologie-SeTIS-Bxl-version-2016.pdf

Canada 1. (2017). Code de déontologie de l’Ordre des traducteurs, terminologues et interprètes agréés du Québec. http://legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/fr/pdf/cr/C-26,%20R.%20270.pdf

Czech Republic. (2017). Jednota tlumočníkůa překladatelů ethical code. http://www.fit-europe.org/vault/ethics-jtp.html

Denmark. (2017). Danish association of state-authorized translators and interpreters code of ethics. http://www.fit-europe.org/vault/deont/dk-auth-eth.html

FIT Europe. (2017). FIT Europe member associations codes of ethics. http://www.fit-europe.org/vault/deont/European_Code_%20Professional_Practice.pdf

France 1. (2017). Société française des traducteurs professionnels : Charte du traducteur. http://www.fit-europe.org/vault/charte-SFT.html

France 2. (2017). Charte de l’interprétariat médical et social professionnel en France. https://www.unaf.fr/IMG/pdf/charte-signee-scan19-12-2012.pdf

Germany ADÜ. (2017). Nord Berufs- und Ehrenordnung. http://www.fit-europe.org/vault/ber-ADUN.html

Germany ATICOM. (2017). ATICOM Berufs- und Ehrenordnung. http://www.fit-europe.org/vault/Ber-ATICOM.html

Germany BDÜ. (2017). Berufs- und Ehrenordnung. http://www.fit-europe.org/vault/ber-BDU.html

Germany VÜD. (2017). Berufs- und Ehrenordnung. http://www.fit-europe.org/vault/ber-VUD.html

Greece. (2017). PEEMPIP code of ethics. http://www.fit-europe.org/vault/deont/PEEMPIP_Ethics_en.pdf

HIN. (2007). National standard guide for community interpreting services in Canada. http://www.multi-languages.com/materials/National_Standard_Guide_for_Community_Interpreting_Services.pdf

IMIA. (2006). Code of ethics for medical interpreters. http://www.imiaweb.org/code/default.asp

INTERPRET. (2015). Code professionnel des interprètes communautaires et des médiateurs/trices interculturel-le-s. http://www.interpretavic.ch/assets/berufskodex_2015_fr.pdf

Ireland 1. (2017). Irish translators’ & interpreters’ association code of practice and professional ethics. http://www.fit-europe.org/vault/ITIA_code_ethics.pdf

Ireland 2. (2017). Irish translators’ & interpreters’ association code of ethics for community Interpreters. http://www.fit-europe.org/vault/ITIA_code_interpreters.pdf

Italy. (2017). Associazione italiana traduttori e interpreti: Codice deontologico http://www.fit-europe.org/vault/deontologia-AITI.html

Netherlands. (2017). Netherlands association of interpreters and translators code of honour. http://www.fit-europe.org/vault/Erecode-ngtv.html

Poland. (2017). Code du traducteur assermenté de l’association polonaise des traducteurs economiques, juridiques et judiciaire. http://www.fit-europe.org/vault/codeTEPIS.html

Sweden. (2017). The Swedish association of professional translators code of professional conduct. http://www.fit-europe.org/vault/deont/SFO-ProfPractice-en.pdf

Turkey Ceviri Dernegi (CN). (2017). Mesleki ve etik ilkeler bildirgesi [Code of professional ethics]. http://www.ceviridernegi.org/meslekivetik.html

UK. (2017). Institute of translation & interpreting code of professional conduct. http://www.fit-europe.org/vault/ITI-conduct-ind.pdf

USA 1 ATA. (2017). ATA Code of ethics and professional practice. https://www.atanet.org/governance/code_of_ethics_commentary.pdf

USA 2 NCIHC. (2004). A national code of ethics for interpreters in health care – National council on interpreting in health care. https://www.ncihc.org/assets/documents/publications/NCIHC%20National%20Code%20of%20Ethics.pdf